by Ann Y. Smith

Since the early 19th century, Connecticut towns have been intentionally embellished with public sculptures, many by prominent American designers. At least 500 of these publicly accessible, noncommercial sculptures were erected in the state before the mid-20th century, and since 1978, public agencies and private foundations have commissioned more than 400 new works. The evolving concerns and values of the state’s citizens are reflected in the changing purposes, placement, and styles of these public monuments.

Cemetery Memorials

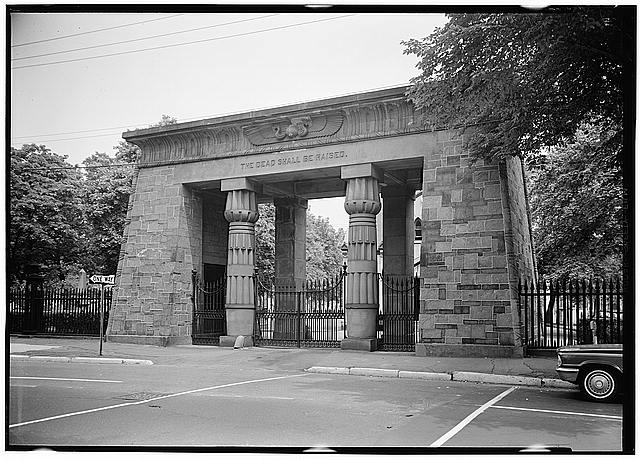

From the beginning, Connecticut towns memorialized their departed through grave markers with powerful symbolic images. Burying grounds continued to house some of the most evocative outdoor sculptures, particularly during the mid-19th century when private associations, motivated by aesthetics as well as piety, created cemeteries intended to help the living consider the spiritual life after death through romantic landscapes and monuments.

Cedar Hill Cemetery in Hartford and Riverside Cemetery in Waterbury stood at the forefront of this movement, with families commissioning figurative and allegorical monuments to departed family members in picturesque garden settings. While New Haven’s Grove Street Cemetery predates this movement, the cemetery’s gate was designed in this spirit in 1845 by New Haven architect Henry Austin. The gate’s Egyptian Revival style was thought to be particularly appropriate for cemeteries.

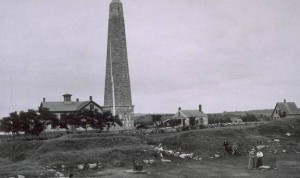

Ithiel Town, Groton Monument, 1830, Groton – Mystic Seaport

In the 19th century, communities also honored local men who had died in war by emphasizing that they had defended the cause of American liberty, a matter of increasing concern during the years leading to the Civil War. In 1830, citizens dedicated a memorial, designed by Ithiel Town’s New Haven architectural firm of Town and Davis, at Fort Griswold in Groton to commemorate patriots slaughtered there by British troops during a Revolutionary War battle. Town designed a modified obelisk. (An obelisk is an Egyptian single-column form featuring a four-sided taper with a pyramid top that was widely recognized in the 1800s as a symbol of eternity.) At the centennial of the battle in 1881, the local memorial committee extended the obelisk to a height of about 134 feet.

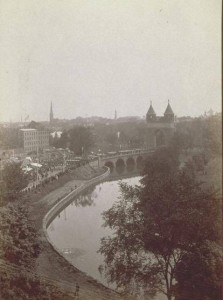

1886 dedication ceremony of the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch, Bushnell Park, Hartford – Connecticut Historical Society

Civil War Memorials

Nearly half of the 19th century’s public monuments were erected as war memorials, with examples found in nearly every Connecticut town. At least 135 Civil War monuments were created in the state. Many of these were expensive undertakings, prompting debates within towns about the imagery, cost, and placement of the monuments, but their creation, sometimes long after the war’s conclusion, is a tribute to the deep anguish caused by the conflict. Among the many notable examples in the state is the 1886 Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Arch in Bushnell Park. Designed by Hartford architect George Keller, its immense Gothic span connects two towers, which straddle a road wide enough to accommodate cars today and, at the time of its opening, carriages.

Many of the state’s Civil War monuments depict soldiers, but several present an allegorical figure of Victory, a strong and virtuous woman based on popular Roman models. This stately figure offered wreaths to the victors and, sometimes, mercy to the vanquished. Notable examples are found in Hartford and New Haven.

Randolph Rogers, Genius of Connecticut, 1878, plaster model, Hartford

In Hartford, a replica of the Genius of Connecticut (originally known as The Angel of the Resurrection, a somewhat funereal title given by the sculptor to other commissions, including his memorial for Hartford’s Samuel Colt) is displayed in the Connecticut State Capitol Building. Strong and protective, she holds the state flower (the mountain laurel) in one hand and the wreath of immortality in the other. A wreath of oak leaves (from the state tree) adorns her head. Created by Randolph Rogers, a prominent Rome-based American sculptor, the original bronze figure took her place atop the capitol building in 1878. The statue stood on the building’s dome until the hurricane of 1938 damaged it. Then, in 1942, it became scrap metal to support the war effort. Rogers’ original plaster model of the statue survived, and after being displayed inside the capitol for many years, it provided the basis for the bronze replica now on display in the rotunda.

The Angel of Peace, which tops the New Haven Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, reprises the classical image of a strong woman bearing wreaths and was erected on an obelisk at the top of East Rock Park in 1887 following an attenuated competition for the commission. The monument was designed by a New York partnership of sculptors trained in Europe: John Moffitt, an English artist living in New York, and Alexander Doyle, who had studied in Florence and Rome. From its prominent position at the top of East Rock, the sculpture overlooks the city harbor. Another elaborate example of an allegorical figure in a similar spirit can be seen in the 1884 Soldiers’ Monument. This Civil War memorial in Waterbury was designed by George Bissell, a New Preston native then living in Paris.

Later Wars Remembered

War memorials continue to be commissioned in Connecticut towns. Often these list local men and women lost in conflicts of the 20th and 21st centuries. Victory of Mercy (1947) at the Loomis Chaffee School in Windsor commemorates those who died in service during World War II. Evelyn Beatrice Longman, who moved to Windsor at the height of her career, designed this poignant and traditional image of an angel ministering to a fallen soldier. Longman was the first woman sculptor accepted as a member of the National Academy of Design and one of the sculptors who helped execute Daniel Chester French’s Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC.

In Search of Heroes

Following the celebration of the nation’s Centennial in 1876, many Americans were attracted to the altruistic ideals they attributed to America’s past. They restored colonial homes, collected American antiques and searched their genealogies to establish connections with ancestors who may have been patriots. As a part of this Colonial Revival, some also sought to honor America’s heroes through outdoor sculpture. Many of these monuments depicted political and military leaders of the past as well contemporary civic leaders who the memorialists felt exemplified the best that American character and the nation’s story had to offer.

Stanford White, Battell Fountain, 1889, Norfolk – Connecticut Historical Society

One such hero was the Marquis de Lafayette, the French general who brought troops and hope to the American cause during the Revolution. While living in Paris, Connecticut native Paul Wayland Bartlett designed an equestrian figure of Lafayette, which had been commissioned for the Louvre Museum as a gift from American school children to the people of France. Mrs. Frances Storrs purchased a copy for Hartford in 1932; it now stands on a traffic island in front of the State Capitol.

Connecticut native Nathan Hale, the Revolutionary War spy who was credited with declaring, “I regret that I have but one life to give for my country,” during his trial for treason against England, became an icon in story and public sculpture across the nation and in his home state. Henry Austin designed the state’s first monument to Hale: an obelisk erected in 1846 near his birthplace in Coventry that was funded by the State Legislature and private donations. Over the next century, many additional monuments to the youthful patriot were erected around the nation. The celebration of Hale’s idealism flourished in Connecticut during the Colonial Revival. Bela Lyon Pratt, a Yale graduate and prominent American sculptor, was commissioned as far back as 1898 to create a somber figure to stand before Hale’s student residence at Yale. Copies were made for Fort Nathan Hale in New Haven and the Connecticut Governor’s Residence.

Reformers and Industrialists

By the end of the 19th century, sculpture honored accomplished citizens in other fields. For example, in 1888, Daniel Chester French depicted Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet and Alice Cogswell for the college in Washington, DC, that later became Gallaudet University. Gallaudet taught Alice, the deaf daughter of a Hartford physician, sign language and helped found the American School for the Deaf, the first permanent educational institution for deaf students in the United States. French’s statue of Gallaudet and Cogswell was recast in 1924 for the American School for the Deaf, now in West Hartford.

Daniel Chester French, Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet and Alice Cogswell, 1888 (cast 1924), bronze, West Hartford – Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

During this same period, philanthropists in the state honored their ancestors with public projects that benefited their communities. These were particularly popular during the “City Beautiful” movement at the turn of the 20th century when philanthropists and city planners worked to improve public amenities in urban areas. Some built parks and bridges. Others built refreshing fountains at busy intersections in the growing cities.

In Bridgeport, the Wheeler family honored their ancestor Nathaniel Wheeler, an inventor and industrialist, with a sculptural fountain in 1912. Designed by Gutzon Borglum, the sculptor of Mt. Rushmore and a Stamford resident, it provided lighting at the intersection as well as fresh water for pedestrians, horses, and cars. Similar amenities for travelers were offered at other towns around the state, including: Norfolk (1889, donated by the Eldridge family in honor of the Battells, local cultural leaders and benefactors); Naugatuck (designed in 1896 by McKim, Mead & White and donated to the town by the Whittemore family); and Ridgefield (designed and donated in 1915 by the nationally prominent architect and then-resident Cass Gilbert).

The 1918 Perry Memorial Arch at the entrance to Bridgeport’s Seaside Park was designed by architect Henry Bacon as a bequest to the city from William Perry, a local industrialist who also served as president of the city’s park commission. The monumental structure is reminiscent of the triumphal arches that ornamented European cities, most famously in Paris and Rome.

Karl F. Lang, Timothy Ahearn Monument, 1937, bronze, New Haven – Dave Pelland, CTMonuments.net

Public Funding Re-emerges

In the 1930s, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and related federal programs supported art for the public, marking a new era of government funding. Outdoor sculpture in Connecticut funded by these programs include a World War I memorial, which honors Corporal Timothy Ahearn and was designed by Karl Lang, in New Haven’s West River Memorial Park and the 22 life-sized figures Theodore Monaghan designed for the Bushnell Park Nativity Scene in Hartford. Most sculptors associated with the WPA, however, did small-scale interior work such as bas-relief and portrait busts for schools and courthouses.

The 1900s: Politics and Abstraction

In the second half of the 20th century, artists created works that reflected deeply felt political concerns and works that were conceived in abstract forms. New sponsors, including public agencies, corporations, and foundations, recognized the value of public art for the image and status of the community and the sponsor.

One of the most powerful sculptures of this period in Connecticut is the work of Claes Oldenburg, then admired as an artist working with images from American pop culture. His Lipstick Ascending on Caterpillar Tracks, designed in 1969 and installed in 1974, was created without approval from Yale, where the piece was installed to serve as a rallying point for students protesting the Vietnam War. The phallic form of the lipstick could be inflated to announce anti-war rallies.

Claes Oldenburg, Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks, 1969-74, New Haven

Other artists also brought modern ideas to outdoor projects in the state. Roxbury-based Alexander Calder, whose monumental abstract sculptures were being erected in hundreds of cities around the world, created Stegosaurus in 1973 for the plaza separating the Hartford City Hall and the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. Two blocks away, Carl Andre’s minimalist work Stone Field Sculpture was installed in 1977 with funding from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and, controversially, the city. The piece, consisting of local boulders arranged in a grid, was an abstraction of the nearby historic graveyard, an iconic symbol of a Connecticut village center.

Across the nation, prominent American artists created large-scale modern sculptures that were constructed at Lippincott, Inc., in North Haven, one of the most highly respected fabricators in the country in the second half of the 20th century.

Leo Jenson, Frog Bridge, 2000, Willimantic

New Sponsors

The NEA-funded Andre project in Hartford was one of many works created in the final decades of the 20th century that financial support from the federal, state, and local governments made possible. The state of Connecticut adopted a program in 1978 that directed 1% of the budget for state building projects to be used for the purchase or commissioning of artwork. Several Connecticut towns, including New Haven, Stamford, and New Britain, have operated similar “percent-for-art” programs. One of the most endearing works created with public funding is Willimantic’s Frog Bridge, which features artwork designed in 2000 by Ivoryton artist Leon Jensen. Piers on the bridge take the form of whimsical frogs (representing a local legend, the 1754 Battle of the Frogs), who sit atop giant spools of thread (a reference to the city’s historic textile industry).

Private foundations and corporations have also sponsored public sculpture in recent years. In 2008, a sculpture walk along the Hartford and East Hartford banks of the Connecticut River was dedicated as part of a larger Riverfront Recapture project. Underwritten by the Lincoln Financial Group, the works are intended to reflect the life and values of Abraham Lincoln. The Hollycroft Foundation has instigated the Sculpture Mile, featuring contemporary sculpture on public streets in Madison, Middletown, Ivoryton, and West Haven.

For more than two centuries, public sculpture has ornamented Connecticut communities. These works embrace local memories of important events and people, add an element of civility to the shared public space, and provoke public discussion about our current communities and shared values.

Ann Y. Smith, a museum director and curator working in Connecticut for 30 years, is a writer and public speaker specializing in the state’s cultural history.