By Diana Ross McCain

The independent town has been the foundation of Connecticut government from the arrival of the earliest English settlers in the 1630s down to the present. Today there are 169 incorporated towns in the state; the newest, West Haven, was created in 1921. That number—and the modern map of Connecticut—is the end result of more than 375 years of settling, splitting, shuffling, snipping off, and stitching together tracts of land.

Congregational Faith Shapes Colonial Land Division

The demands of the Congregational faith exerted the greatest influence on the first century and a half of Connecticut town creation. Connecticut’s Puritan founders made Congregationalism the colony’s established religion. This meant every taxpayer had a legal obligation to pay toward the church’s support and that every resident was required to attend day-long worship services at a meetinghouse on Sunday. Congregationalists were organized into self-governing churches, independent of any other religious body or hierarchy.

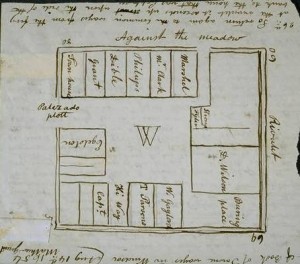

John Warner Barber, Plan of the ancient Palisado Plot in Windsor – 1634, 1835 – Connecticut Historical Society

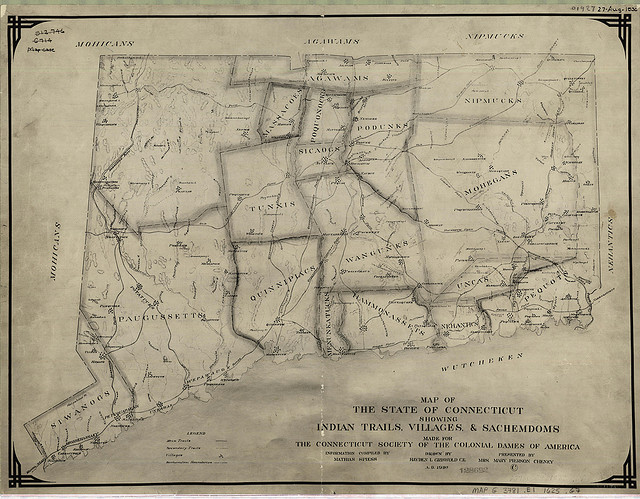

The earliest pattern of town formation began with a group of individuals receiving permission from the General Assembly, Connecticut’s legislative body, to settle a tract of land. These “proprietors” would take up residence on the granted land, apportioning some acres among themselves and reserving outlying land to be divided up among their descendants. In many cases, it is recorded that title for these lands had been acquired from the resident Native tribes. The history of such sales is, however, fraught with questions. Transactions, even voluntary ones, typically took place within a legal system defined and controlled by the English parties, and unfamiliar to the Native peoples. Also, various forms of coercion, including harassment and, from the late 1600s on, pressure to cede reservation lands granted under colonial law, played a role in some transactions.

The European settlers of these fledgling communities gave top priority to the establishment of religious and civic institutions. Residents would begin by gathering for Congregational worship in individual homes. When a settlement had enough taxpayers to financially support its own minister and build its own meetinghouse, it could seek from the General Assembly authorization to be an ecclesiastical society.

Establishment as an ecclesiastical society empowered the group to manage all religious affairs within its defined geographic area. Similarly, incorporation by the General Assembly as a town allowed residents to manage secular affairs, such as election of local officers and representatives to the General Assembly, passing and enforcing ordinances, and levying and collecting taxes, within their boundaries.

In the case of communities being formed from freshly settled land grants, often the town was incorporated first, with the ecclesiastical society being created anywhere from a few months to a few years afterward. By 1669 Connecticut boasted 21 incorporated towns, each of which encompassed the same boundaries as its corresponding ecclesiastical society.

This sequence of colonization—from proprietor grant to incorporated town then ecclesiastical society—continued to occur in areas of Connecticut not yet settled by Europeans until the mid-1700s. At that point, the entire colony had been apportioned. In the last decades of the 17th century, however, this original process overlapped with a new pattern of land division: existing towns began divide into multiple ecclesiastical societies, which in a reversal of the original pattern, were often harbingers of new towns.

Hard-to-travel Distances Spur Formation of New Towns

The difficulty involved in making the legally required weekly trip to Sabbath services provided the primary spur for forming a new Congregational society. As people moved into outlying areas of existing towns, the distance to the location of the original meetinghouse increased. For residents of these farther reaches of a town, attending Sabbath services could require a long, arduous, sometimes dangerous trip of 5 or 10 miles or more, usually on foot, along crude dirt roads that could be snow-clogged, icy, muddy, or dusty depending on the season. Traveling to church often required traversing unbridged streams or even major waterways such as the Connecticut River.

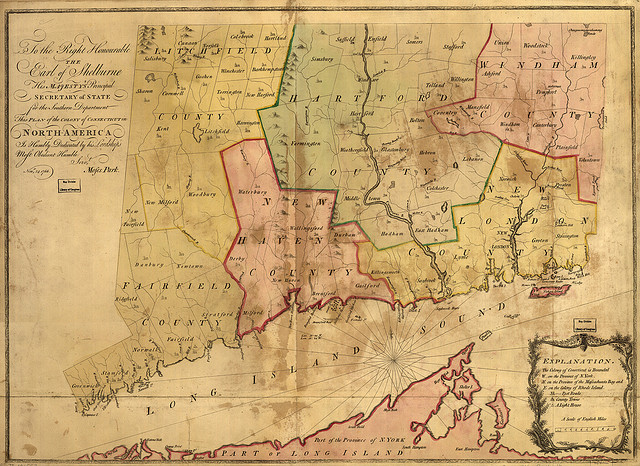

Colony of Connecticut in North-America by Moses Park, 1766 – University of Connecticut Libraries’, Map and Geographic Information Center (Magic)

Not surprisingly, as soon as a community at an inconvenient distance from its meetinghouse had enough taxpayers to hire their own minister and build their own house of worship, they would petition the General Assembly for permission to become an autonomous ecclesiastical society.

As the populations of towns grew and spread out, new ecclesiastical societies proliferated. For example, by 1767 Middletown had been divided into five ecclesiastical societies—two on the eastern side of the Connecticut River. By 1790 there were 203 Congregational societies in the state, which meant most people lived no more than a manageable three miles from a meetinghouse.

But for civil purposes, the societies were still part of the larger town. There were no voting booths, no polling precincts, and participation in local government required attendance at town meetings, which were typically held near, or even in, the meetinghouse in the oldest part of town. Prior to the American Revolution, this did not usually present an insurmountable barrier for voters who lived on the outskirts since most towns held only one or two meetings annually. Even so, some Congregational ecclesiastical societies, particularly ones separated from the site of their local government by major bodies of water, sought incorporation as autonomous towns for civil reasons in the late 1600s and early 1700s. For instance, the part of Wethersfield on the eastern side of the Connecticut River incorporated as the town of Glastonbury in 1693, and the section of New London east of the Thames River incorporated as Groton in 1705.

From the mid-18th century onward, most new towns formed when an ecclesiastical society in an existing town sought incorporation as an independent town. By 1790 more than two dozen new towns had been created in this way.

Sometimes it was not a single distinct ecclesiastical society that sought incorporation as a town, but parts of societies that lay in several different towns for whom circumstances dictated a joining together. In 1785 residents in adjacent portions of the eastern Connecticut towns of Windham, Pomfret, Brooklyn, Canterbury, and Mansfield petitioned the General Assembly for incorporation as a new town, citing “their remote and difficult circumstances—ten and even fourteen miles from the seat of business, amounting at times to a total deprivation of those rights and privileges which God and nature have given them.” The following year those fragments of five towns united into the town of Hampton.

New Constitution and Industrialization bring Change

A new state constitution adopted by Connecticut in 1818 disestablished the Congregational church, which meant that religion’s ecclesiastical societies no longer automatically served as a template for new towns. The Constitution of 1818 also eliminated property ownership as a qualification for voting. Many more men now were entitled to cast ballots in local elections, increasing interest in making it as convenient as possible to attend town meetings.

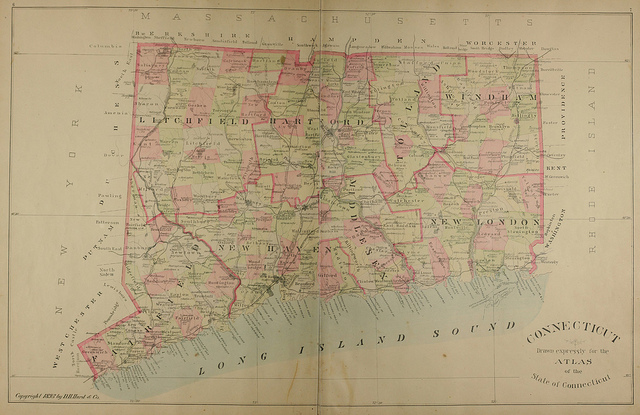

Town and city atlas of the State of Connecticut, Boston: MA: D.H. Hurd & Company, 1893 – University of Connecticut Libraries’, Map and Geographic Information Center (MAGIC)

Increases and shifts in population and the development of new centers of commerce and industry also directed town formation in 19th-century Connecticut. In 1783, for example, the portion of Hartford east of the Connecticut River, was incorporated as the town of East Hartford. It was not long, however, before the balance of power in the new town tipped against the interests of residents of Orford Parish, the easternmost part of East Hartford. “Orford Parish as the newer and larger part of the town needed more new roads and bridges than did the older section, and there were squabbles about this,” wrote Manchester historian William Buckley. Further, “it was still necessary to go to East Hartford center, about nine miles for some residents of the parish, to attend town meetings and do any other legal business except paying taxes.” In 1823 Orford Parish achieved incorporation as the town of Manchester.

The incorporation of Middlefield provides another example of how population and industrial growth influenced town formation. The southwestern portion of Middletown, settled in the early 1700s, became the ecclesiastical society of Middlefield in 1744. More than a century later, Middlefield had become a distinct population center, with its own industrial base anchored by the Metropolitan Washing Machine Company. Middlefield was incorporated as a town in 1866, having made a deal by which it would assume responsibility for one-tenth of Middletown’s Civil War and other municipal debts. But Middlefield benefited from the arrangement since, as an independent town, it was responsible not for a portion of the entire cost of Middletown’s support of the poor but only for those few impoverished individuals who actually lived in Middlefield.

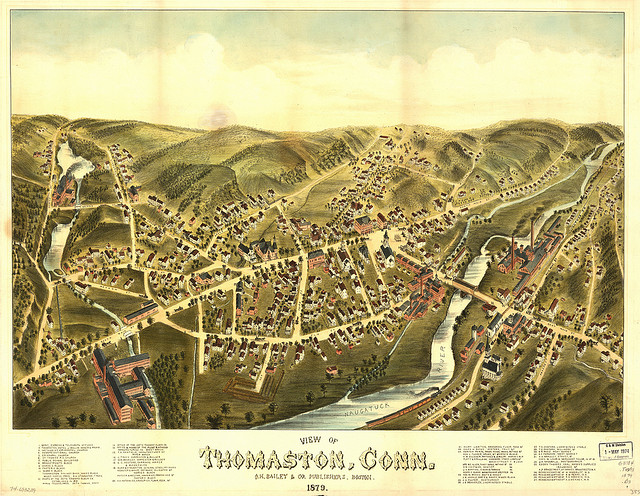

It was not uncommon for a town to split in two, for one of those halves to be divided, and then one of the resulting halves to be divided again. In 1780, for instance, the Northbury and Westbury societies of Waterbury were incorporated as the town of Watertown. Just 15 years later, residents of Watertown east of the Naugatuck River successfully sought incorporation as the town of Plymouth, citing the fact that their location made it “very inconvenient to do this town business owing to the badness of the roads, length of the way, and other inconveniences.” In 1875 it was Plymouth’s turn be cut in half, with the incorporation of its western portion as a new town named Thomaston for Seth Thomas, whose burgeoning clock factories had made the community an industrial center with a global reach.

View of Thomaston, Conn. 1879, Boston, MA: O.H. Bailey, 1879 – University of Connecticut Libraries’, Map and Geographic Information Center (MAGIC)

Independent Town Model Enters the 21st Century

After 375 years of town formation the map of Connecticut resembles a jig-saw puzzle, with pieces of diverse sizes and shapes. The 169 towns range dramatically in size from New Milford’s 62 square miles to Derby’s 5. Additionally, five state-recognized Native American tribes hold reservation lands within Connecticut.

From time to time residents of a portion of one town or another will talk about seceding over a contentious issue, but that figure of 169 has remained constant for more than 90 years. However, in recent decades some have come to see the independent Connecticut town as a quaint anachronism, unsustainably inefficient in the modern economy. Regionalization—the collaboration of two or more towns in providing services—has been proposed as a solution, and it has been instituted with success in such situations as regional school districts, of which there are 19. But the independent town, from Union with 850 residents to Bridgeport with more than 144,000, remains the essential unit of Connecticut government.

Diana Ross McCain, formerly Head of the Research Center at the Connecticut Historical Society, has been writing about Connecticut history for 30 years.