By Nancy Finlay

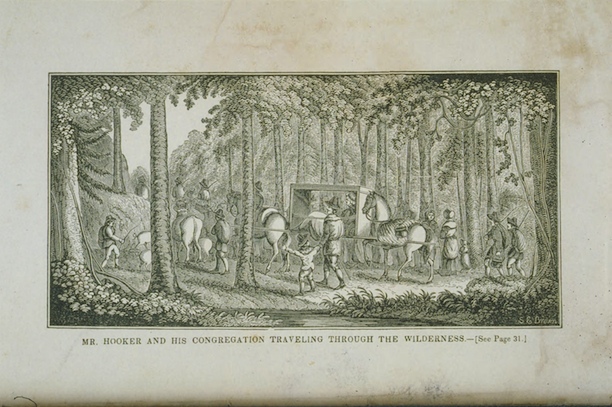

Many 19th-century histories of Connecticut feature wood engravings of Thomas Hooker and his followers making their way through the wilderness on their way to found Hartford. Although Hooker and his followers look very much like any pioneers, their primary motivation was not a desire for new land. They definitely did not set out to found a new state. They saw themselves as God’s people, and they set out as a congregation to establish their church on the banks of the Connecticut River.

The Reformation swept through Europe in the 16th century. The Protestants wanted to cleanse the church of what they saw as corruption, to return to simplicity and purity of early Christian worship, without vestments and incense and elaborate rituals. They wanted a more direct relationship with God, without the intervention of priest or Pope.

English Puritans escaping to America. – New York Public Library Digital Collections, Art and Picture Collection

King Henry VIII established the Anglican Church in England to escape the authority of the Pope but retained much of the liturgy and creed of Roman Catholicism. As Thomas Hooker put it, Henry “cut off the head of the English church but left the body intact.” Puritanism arose as a movement that sought to reform the Anglican Church along the lines of Continental Protestantism. The fortunes of Protestants in England waxed and waned under Henry’s immediate successors.

During the long reign of Henry’s daughter Elizabeth I (from 1558 to 1603), Anglicanism became firmly established. The Church tolerated ministers with Puritan leanings and Puritanism became widespread in some areas. James I, a Scottish Presbyterian who succeeded Elizabeth in 1603, proved much less tolerant, and his son Charles I was even worse. Puritan ministers needed to conform or faced losing their positions. Many, like Thomas Hooker, fled to Holland to escape arrest and persecution. They began to look to America as a place to create an ideal Puritan community and be free to worship as they chose. During the 1630s, more than 21,000 Englishmen left their homes and crossed the Atlantic to pursue God’s work in New England.

Puritanism Arrives in America

It all happened very rapidly. The Pilgrims landed at Plymouth in 1620. The founding of Boston took place in 1630. During the following decade, several different groups of devout Puritans left the area around Massachusetts Bay and moved west to the Connecticut River Valley. A few adventurous souls occupied the future sites of Windsor and Wethersfield in the early 1630s. Settlers established a fort in Saybrook in 1635. Hooker and his party arrived in Hartford in 1636. A Puritan congregation led by John Davenport established New Haven as a separate colony in 1638.

Settlers of Connecticut: In 1636, Mr. Hooker & his Congregation (about 100 in number) travelled through the Wilderness and began the settlement of Hartford, Conn. – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Illustrated

These early towns grew rapidly, and new towns developed in outlying areas. The church was the most important building in these early Connecticut communities. Known as the meetinghouse, it not only served as a house of worship, but might also function as an armory and courthouse and a place to hold town meetings.

Accepted protocols required the entire population to attend church services, but only a small minority earned admittance to full church membership. These church members enjoyed considerable power and influence. They chose and ordained their own ministers and elected elders and deacons to administer the church. They voted to admit new members and to punish or dismiss those who offended against God’s laws. Although the Puritans came to America seeking the right to worship as they wished, there was no religious liberty in Puritan Connecticut. Heretics—and that included anyone who was not a Puritan—faced fines, banishment, imprisonment, or corporal punishment.

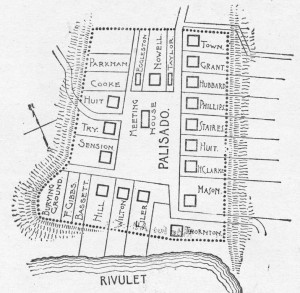

Plan of the Palisado, the original layout of the town of Windsor – Windsor Historical Society

So important was the church and so effectively did it order people’s lives that it was more than two years before the settlers of Hartford, Windsor, and Wethersfield perceived a need for a civil government. The Fundamental Orders, adopted in January 1639, provided the first formal framework for the colony. Although Thomas Hooker famously asserted that “the choice of public magistrates belongs unto the people,” only a small proportion of the population—adult male householders and landowners—was qualified to vote.

Connecticut Feels the Effects of the English Civil War

Increasing conflict back in England between Charles I and his Puritan subjects marked the decade of Connecticut’s founding. In 1642 a full-scale civil war broke out, culminating in the arrest and execution of the king and the establishment of the Puritan leader, Oliver Cromwell, as Lord Protector. England became a Puritan state. In America, the Anglican colonies to the south abhorred this development, but Puritan colonies such as Connecticut and the New Haven Colony saw Cromwell’s success as an extension of their own efforts at reform and offered up prayers of thanksgiving.

Many prominent Connecticut Puritans returned to England to fight in Cromwell’s armies and to serve in his government. During this time, New England Puritans functioned more or less independently, developing enduring traditions of self-government. Following Cromwell’s death, however, the monarchy returned to power in 1660 with the son of Charles I as the new king. Connecticut initially expressed reluctance to recognize the new government, and did so only in March 1661. New Haven waited even longer, until August 1661.

John Winthrop Jr., the son and namesake of the Governor of Massachusetts, and a man who proved instrumental in the founding of Saybrook and New London, began a seven-year run as Governor of Connecticut in 1659 and went to England in 1661 to obtain an official Charter from Charles II. This important document essentially confirmed the Fundamental Orders and assured Connecticut’s continued existence as a Puritan colony.

In the early 1700s, Connecticut adopted a toleration act based on the English Toleration Act of 1689, thus introducing a measure of the religious freedom lacking in the early colony. Dissenters, however, needed to register with the town clerk, and their taxes still supported the established Puritan church. Anglicans, who finally gained a foothold in Connecticut, became classified as dissenters.

Yale College, founded in 1701 to “promote the Power and Purity of Religion and Best Edification and peace of these New England churches,” was initially a bastion of Puritan orthodoxy, but began evolving steadily in the direction of Anglicanism. In the 1730s, the Great Awakening, a religious revival spearheaded by Jonathan Edwards, led to additional factionalism within Connecticut’s religious community. The division of Puritans into New Lights (those who supported the revivals) and Old Lights (opponents of the revivals) was an innovation of James Davenport, the great-grandson of John Davenport of New Haven. Davenport was a fiery speaker who denounced his fellow ministers and presided over the burning of hundreds of books at New London. Connecticut expelled him from the colony in 1742, and Massachusetts banished him later the same year.

The Spread of Religious Diversity

Other religions may have made inroads in 18th-century Connecticut, but Puritanism, now known as Congregationalism, remained the faith of the ruling elite, and the Congregational Church remained the established church of the colony. The majority of the population remained Congregationalist. Like their Puritan forebears, Congregationalists believed that governments existed for the benefit of the people, and that governors needed to rule according the will of God.

During the 1760s, Congregational ministers preached against the Stamp Act. While both New Lights and Old Lights opposed the Stamp Act, once it became law, the Old Lights believed in its enforcement. The New Lights, however, preached resistance, if not open rebellion. In a tumultuous election in 1766, New Lights replaced the Old Light governor and councilors. The New Light Lieutenant-Governor, Jonathan Trumbull, went on to become Connecticut’s war governor, the only colonial governor to remain in office through the Revolution.

During the Revolution, Connecticut Congregationalists remained almost invariably patriots; Connecticut Anglicans often became Loyalists. This was not the case in other parts of the country, especially the South, where most of the Anglicans backed the patriot cause.

Following the war, religious diversity in Connecticut continued to increase. In 1784, Connecticut finally passed an “Act for Securing the Rights of Conscience,” that secured religious freedom for those “professing the Christian religion,” of whatever denomination, and decreed they no longer be taxed to support the Congregational church. But non-Christians could be taxed to support the established church, and Congregationalism remained the established state religion until 1818, when Connecticut passed a new state constitution, replacing the laws of the old colonial charter obtained in 1662. This was not the end of the power and influence of the descendants of the Puritans, however. The Congregational Church retained much of its prominence and Congregationalists continued to play a disproportionate role in Connecticut politics well into the 20th century.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.