By Briann Greenfield

A cultural movement as well as an architectural and decorating style, the Colonial Revival of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was inspired by a romantic veneration of the early American past. Enthusiasts sought to bring what they believed to be traditional values and aesthetics into contemporary life by preserving old buildings and artifacts, staging reenactments of historic events, manufacturing new goods in past styles, and creating works of art and literature depicting early American scenes.

The Colonial Revival was national in its scope, but as a state rich in historic resources, Connecticut became inextricably linked with the movement, supplying both symbolic imagery and active adherents. Although interest in the colonial era persists today, the heyday of the Colonial Revival occurred as rapid urbanization, industrialization, and immigration encouraged many Americans to seek refuge in the perceived simplicity of the past.

Origins and Imagery

The Connecticut Cottage at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition

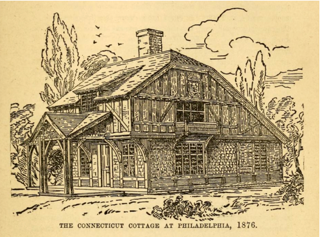

Most scholars tie the emergence of the Colonial Revival to the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Americans marked the milestone with the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, the first official world’s fair in the United States, held in Philadelphia, a city with its own rich colonial past. With displays of American manufacturing, the fair celebrated the nation’s rush to progress, but its exhibits also provided many comparisons to the past. Among these was Connecticut’s state building, the “Connecticut Cottage.” Designed in the style of a half-timbered medieval structure, the house would not conform to modern knowledge of colonial-era Connecticut architecture. But visitors to the world’s fair recognized it as historic and were assisted in that judgment by the placement of an old-fashioned well-sweep (a device for raising and lower water buckets) in the front yard. The interior also included relics of the past: a gun that had belonged to Revolutionary War hero General Israel Putnam, an antique tall clock, relics of the Charter Oak, and what would become the icon of the Colonial Revival, a spinning wheel positioned in front of the fireplace.

Artists and writers working in Connecticut helped bring such idealized images of early American life to a wider public. Writers such as Harriet Beecher Stowe set stories in puritan New England. Similarly, Impressionists Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf and Adelaide Deming created bucolic scenes based on New England landscapes. Often, they depicted old homes in Lyme or Litchfield, the latter of which had created a comprehensive plan in 1913 to remodel or rebuild all public and business buildings in colonial styles.

Inspired Nostalgia Trumps Historical Accuracy

Reenactors at 1908 Bulkeley Bridge dedication recreate Thomas Hooker’s 1636 landing – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

In most cases, participants in the Colonial Revival were more concerned with preserving the spirit of the past than with strict adherence to historical accuracy. Proponents also drew their inspiration widely, not limiting their enthusiasm for the past to the period when Connecticut was a British colony but embracing the early national period as well. Geography was not a barrier either. When pioneering female architect Theodate Pope Riddle collaborated with the architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White in 1898 to build a sprawling summer retreat for her parents in Farmington, Connecticut, she used Mount Vernon’s southern architecture as her model.

Likewise, Colonial Revival enthusiast might graft visions of the past on to distinctly contemporary events. The dedication of Hartford’s Bulkeley Bridge in 1908, for example, was marked by three days of celebrations, including a reenactment of Thomas Hooker’s historic 1636 landing in Hartford. Men, women and children dressed as Puritans to recreate that landing, which is an early and treasured story in the founding of the Connecticut colony.

Interest in Past Prompts Preservation

Still, this interest in the colonial past proved to be good news for preservation of the state’s historic resources. For example, the state’s first historic house museum was founded in 1891 when the Connecticut chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution preserved a former store and office in which Governor Jonathan Trumbull planned the defense of the Connecticut colony during the Revolutionary War.

The Sons’ sister organization, the Daughters of the American Revolution, preserved the Oliver Ellsworth Homestead (built in 1781) in 1903 and Putnam Cottage (built circa 1690) in 1906. In the 1920s, Connecticut members of the Colonial Dames completed an extensive architectural survey of the state’s colonial and early national buildings that included architectural drawings created by preservationist architect J. Frederick Kelly. By 1933 the state could boast 23 historic house museums, all but one having been built in 1800 or earlier.

Similarly, antique collectors also located, identified and preserved examples of early American craft. Among the earliest of these collectors were Hartford’s Walter Hosmer, a furniture upholster, and Dr. Irving W. Lyon, author of The Colonial Furniture of New England (1891), the first book-length scholarly study of American furniture. Others included Henry Wood Erving, a chairman of the Connecticut River Banking Company credited with discovering a class of richly carved chests indigenous to the Connecticut River Valley; Wallace Nutting, an entrepreneur whose business ventures included a chain of historic house museums, photographs of staged colonial scenes, and a line of reproduction furniture; and George Dudley Seymour, a flamboyant collector whose passion for history was fueled by his devotion to the memory of Revolutionary War captain Nathan Hale. Such collectors helped establish the study of American decorative arts and create important museum collections including those of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, the Connecticut Historical Society, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Past Provides Refuge from Change

Wallace Nutting, A Daughter of the Revolution, Hand-colored photogravure, 1904 – Yale University Art Gallery

Politically, the Colonial Revival was conservative in its leanings. The ancestor-worshipping lineage associations that proliferated beginning in the 1890s worked to preserve the status of old Yankee families during a period of high immigration. Often associated with Revolutionary War heroes or Connecticut statesmen, historic house museums promoted patriotism and respect for government institutions.

Similarly, at a time when many women were organizing for the vote, Wallace Nutting’s popular photographic prints depicted women in traditional roles as genteel ladies and productive housewives. But the real women who worked to preserve historic buildings during the Colonial Revival did not restrict themselves to the domestic sphere. To carry out their ambitious plans, they took on the very public roles of organizers, spokespersons, and fund-raisers. This is certainly true of Emily Seymour Goodwin Holcombe, whose extensive work as a preservationist included restoring Hartford’s Ancient Burying Ground in 1896 and saving the Connecticut Old State House from demolition in 1909.

Colonial Revival Melds with the Modern

As much as the Colonial Revival idealized the past, it also did much to facilitate the introduction of modern modes of living. In the area of aesthetics, it replaced the fussiness of Victorian design with simpler, almost streamlined, shapes. Colonial Revival motifs could be applied to modern building forms, as in the case of the skyscraper built for the Hartford-Connecticut Trust Company in 1920.

Colonial-styled commodities also fueled the burgeoning consumer culture of the 1920s. Connecticut firms such as Nathan Margolis, Robbins Brothers, and Hitchcock produced furniture in early American styles. Such goods were readily displayed in modern, single-family suburban homes, themselves often adorned with colonial motifs. Indeed, Colonial Revival architecture and interior décor became so closely tied to Connecticut’s suburbs that when the fictional television couple Lucy and Ricky Ricardo moved to Connecticut in 1957, the sixth and final season of I Love Lucy, their new home was Colonial Revival.

Briann Greenfield, PhD, is the former coordinator of the public history program at Central Connecticut State University and current executive director of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.