By Amanda P. Roy

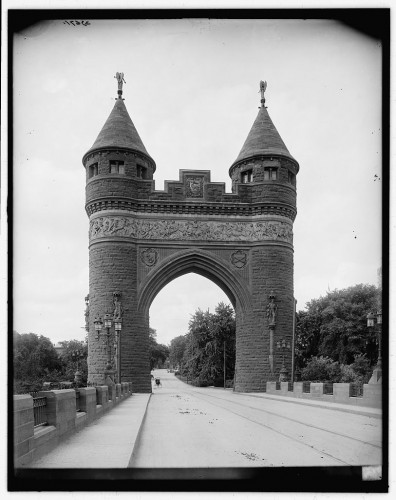

The Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch, dedicated on September 17, 1886, stands as unique for the period in which it was built. It is very likely the first permanent triumphal arch erected in the United States and, unlike other war memorials around the state, does not list the names of those individuals who served or died in the war. Rather, the inscribed dedication more broadly honors the fact that “more than 4000 men of Hartford bore arms in the national cause nearly 400 of whom died in service.” Hartford’s own George Keller, one of the city’s leading architects of the 1800s, designed the Gothic and Romanesque revival monument. Following Keller’s death in 1935, his ashes were entombed in the East tower of the arch and later joined by those of his wife Mary, who died in 1946.

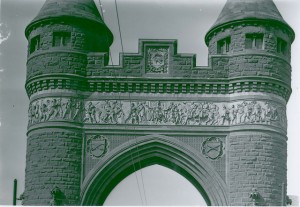

Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch south frieze – Connecticut State Library, State Archives, PG430, Thompson Photographs of Hartford

In 1882, city leaders sponsored a design competition for an arch connected to the Ford Street Bridge that spanned the Park River in Bushnell Park. Despite awarding prizes to the competition’s winners, the committee did not choose any of the submitted designs when feasibility studies indicated that required modifications would exceed the $60,000 budget. Finally, they called on George Keller, who had earlier hoped to be consulted on the project and, when he was not, abstained from the competition. When Keller provided his plan, the selection committee unanimously adopted it.

Detailed Scenes of War and Peace

Builders constructed the arch with Portland brownstone and crafted the friezes with gray terra cotta. The terra cotta friezes, positioned 40 feet above the road, stand 7 feet high and tell the stories of conflict and peace. The northern frieze depicts the Civil War, while the southern frieze commemorates victory and peace. The story of war, sculpted by Samuel Kitson, includes smoking Confederate guns and cannon symbolic of the firing on Fort Sumter and the start of combat. At opposite ends of the panoramic frieze, Union General Ulysses S. Grant surveys the field of battle and naval forces jump from their boats to join the fray.

Bohemian-born American sculptor Caspar Buberl designed the story of peacetime that unfolds on the southern frieze. It tells the tale of Hartford, represented by the seated figure of a woman at center of the scene, welcoming her sons home from battle with laurel wreaths, the traditional victors’ crown. The troops’ journey home is shown in stages, from the dismantling of campsites to the joyous greetings of waiting wives and children. Some of the men travel home by horse or ship; others come injured, leaning on fellow soldiers for support. In addition, the army’s symbol is on the western tower and the navy’s on the east; this serves to separate the two scenes. In all, there are almost 100 full-length human figures sculpted on the friezes.

Sculptures Convey Layers of Meaning

Sculpture of the freed slave on the west tower of the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch – Connecticut State Library, State Archives, PG 400

German-born sculptor Albert Entress designed the monument’s six statues, each of which stands eight feet tall. The figures seek to represent the diversity of Hartford’s war participants by highlighting peacetime trades common to the era. The original six sculptures included a farmer, blacksmith, scholar, merchant, mason, and carpenter. A freed slave, however, replaced the merchant as the final sculpture added to the memorial. The sculptures on the monument’s north side represent the men who left their work to take up arms for the war effort; those on the south represent veterans returning to their normal lives following the fight for the Union.

The arch has two conical roofs, on which sit two angels—Gabriel and Raphael—one playing the trumpet and the other a set of cymbals. Originally made of terra cotta, they were removed and replaced years later by bronze statues after lighting struck one of the originals. In 1986 the city planned a major restoration and rehabilitation to mark the memorial’s 100th anniversary. Using state funds that totaled $1.5 million, architect Dominick C. Cimino oversaw the project to bring the arch to its former glory.

Restored and Rededicated

Trolley under the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch – Connecticut State Library, State Archives, PG 400

Opinions on the structure have varied over the years. The narrow street under the arch caused controversy when city planners proposed and built a trolley line in the 1890s. Later, the narrow roadway caused many a bottleneck when automobiles and foot traffic competed for space. Over time, planners reconstructed sidewalks, covered the Park River, which ran through the park, and removed the Ford Street Bridge. Trinity Street now passes under the arch.

On September 17, 2011, the Connecticut Civil War Commemoration Commission rededicated the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch in Bushnell Park. This ceremony took place 125 years after the original dedication, which coincided with the 24th anniversary of the Battle of Antietam. Those in attendance included city leaders, architect Jim Keller (George Keller’s grandson) who spoke at the ceremony, and Civil War re-enactors who fired a 21-gun salute.

Amanda P. Roy holds a master of arts in History from Central Connecticut State University and is currently a Program Officer for Public Humanities Programming at Connecticut Humanities.