By Ann Y. Smith

The decorative arts are the useful objects of everyday life: furniture, textiles, tableware, lighting, and other furnishings. Crafted of materials such as wood, horn, fiber, ceramics, glass, pewter, tin, and silver, decorative arts reflect life at home as well as the experience of the craftsmen who made them.

Household Furnishings: Markers of Social Change and Status

During the colonial period, Connecticut families built farming settlements in the wilderness connected to central villages located along major rivers and coastal ports. Many of these homes, especially inland, were sparsely furnished, although those of the wealthy were filled with a wider range of household goods.

Decorative carved chest attributed to the Stoughten shop tradition, ca. 1680 – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain and Fair Use.

Before 1740, most homes had only a few pieces of furniture and only the most essential textiles, as well as a small range of iron, horn, pewter, and wooden objects used in the preparation and serving of food. Ceramics, glass, or silver was rare. The few furnishings that a family did own often served multiple purposes. By the mid-18th century, more households owned more furniture. For example, Hartford records of the era list twice as many pieces per household as owned by the earlier generation. These colonists also owned textiles, iron and pewter goods, and imported glassware and ceramics in greater quantity.

Homeowners augmented locally made furnishings with imported goods from England, Europe, or China and the larger American cities (primarily Boston and New York) connected to Connecticut’s coastal trade. Merchants in the colony’s villages facilitated this trade: they sold imported goods to local farmers in exchange for their agricultural surplus. By 1760, for example, merchants in Hartford had 20 warehouses along the river to accommodate the import and export of goods.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, many considered household goods to be the property of women. This included textiles made by girls in anticipation of marriage and furniture commissioned from local craftsmen at the time of a marriage. Traditionally, these dowry furnishings passed on to the woman’s descendants, while the family lands descended to the sons. Therefore, these furnishings provide us with a view of women’s roles in family and society.

Writing-arm chair attributed to Ebenezer Tracy, ca. 1775 – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain and Fair Use.

The second half of the 18th century saw a growing interest in gentility as Connecticut’s economy grew more diversified and its citizens more prosperous. Increasingly interested in polite manners, homeowners sought “refined” fashions in their furnishings. Replacing the multipurpose furniture of a previous generation, they acquired new forms for specialized purposes, such as dining (dining tables), entertaining (card tables), or study (desks and bookcases). Newly popular matching sets of glassware, ceramics, and silver replaced the communal bowls and spoons of the earlier generations. After the American Revolution, furniture and other decorative arts engraved and inlaid with American patriotic symbols found favor.

With the rise of manufacturing in the decades before the Civil War and improved transportation networks, machine-produced household goods replaced earlier handcrafted furnishings. More fashionable and less expensive than the locally made goods, these manufactured wares were produced in larger factories that served the national markets emerging in the 19th century. In Connecticut, furniture, clocks, pewter, and silver production adopted this national manufacturing model with some success for periods in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Handcrafts: A Mainstay of Early Connecticut

Family members made some of the colonial furnishings for use within the household. Craftsmen in the community with specialized training, skills, and tools also made household furnishings. All of these craftsmen also worked as farmers and often performed their crafts seasonally, as the agricultural cycles permitted. By one estimate, a quarter of Hartford County residents were part-time craftsmen by the middle of the 18th century.

In the 1700s, most Connecticut towns had a range of basic craftsmen, including blacksmiths working in metals and “joiners,” or basic carpenters, making plain furniture, house frames, and tools. Some towns also supported coopers, potters, and pewterers.

Several Connecticut towns developed more complex economies and attracted larger populations. These towns were better able to support more specialized craftsmen: cabinetmakers, clockmakers, and silversmiths, some of whom became more widely known and able to export their wares to the nearby region. These more specialized craftsmen gathered in the port towns of New Haven, Norwich, and New London and the early-established county seats like Litchfield. They gathered, too, in the trading and governmental centers along the Connecticut River, at Hartford, Windsor, and Middletown.

The furnishings crafted in Connecticut during the 17th and 18th centuries reveal the training of the maker and the preferences of the user. As a result, furniture and other household goods are distinctive to the region, blending Dutch and English traditions with new fashions from New York or Boston.

By the late 18th century, a number of craftsmen in Connecticut were producing distinctive furniture, textiles, glass, and functional objects in a variety of metals. Surviving examples are highly regarded among modern antiques collectors, scholars, and curators.

Bed attributed to Eliphalet Chapin, ca. 1775 – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain and Fair Use.

Furniture: Distinctive Local Styles and Traditions

Craftsmen in the colony’s earliest communities built distinctive furniture forms, largely based on English medieval traditions. These include carved chests in Windsor and Wethersfield, paneled chests in New Haven, chests with painted floral decoration along the shoreline between Guilford and Saybrook, and, along the coastline near Stratford and Milford, banister-back chairs with a distinctively carved crest.

With the growing prosperity of the 18th century, thriving communities supported furniture-makers working in the fashionable Queen Anne and Chippendale styles. These centers were found in New London County, particularly in Norwich and Colchester; Hartford County, in the shops of Eliphalet Chapin and his followers; and Litchfield County, especially in Woodbury and Litchfield. While conventional wisdom among 20th-century collectors has maintained that “if it’s cherry and quirky” it was made in Connecticut, recent scholarship has identified dozens of distinctive shop traditions and hundreds of furniture-makers active during this period.

Some of these shops were quite large, employing dozens of specialized workers and reaching markets across a region of the state. However, even larger shops manufacturing furniture with power-driven machines eclipsed them after 1830. Lambert Hitchcock was one of the first success stori

Pitcher made by Thomas Danforth Boardman and Sherman Boardman, ca. 1835 – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain and Fair Use.

es in this new method of manufacturing furniture. Working from his factory in the Riverton section of Barkhamsted, where 15 men and 6 women made 15,000 chairs in 1831, Hitchcock shipped the mass-produced chairs to customers across the northeast.

Pewter: Danforth Family and Others Make Their Mark

Pewter is a metal alloy that craftsmen made of tin with copper and other materials and then cast in molds to form bowls, plates, and lighting devices. While much of the pewter used in Connecticut’s homes by the 18th century was imported, immigrant pewter makers also made their mark. The Danforth family was legendary among the many Connecticut pewterers, with 19 makers over 5 generations between 1730 and 1840. Beginning in Norwich in 1733, Thomas Danforth trained his sons whose descendants set up shop in Middletown and Wethersfield as well as Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Ohio.

Many of the Danforth craftsmen were entrepreneurial in their pewter businesses: some worked in brass as well as pewter and other members of the family operated a hardware store and ran peddler routes to Philadelphia. The Boardmans in Hartford, cousins of the Danforths, joined with them to produce and ship pewter throughout New England and the South.

By the middle of the 19th century, many Connecticut pewterers faced competition from goods made of Britannia, a tin alloy with a more silver-like appearance, and from an inexpensive silver product made with a new electroplating process. Many Connecticut pewter makers, largely concentrated in Meriden and Wallingford, revised their production materials and methods. Many of the survivors eventually joined the conglomerate International Silver in Meriden founded in 1898.

Silver

By the middle of the 18th century, silversmiths worked in Connecticut’s larger towns, including Hartford, New Haven, New London, Norwich, and Middletown. Using currency-grade silver, or “coin” silver, they made ornamental objects that literally preserved and displayed a family’s assets. They produced communion cups, beakers, and plates presented to local churches by wealthy benefactors and spoons, ladles, rings, basins, and pitchers for domestic use in affluent homes. Many silversmiths also served their towns as jeweler and watchmaker, and some made other kinds of precision instruments as well as pictorial engravings and maps.

Sauceboat made by Ebenezer Chittenden, ca. 1760 – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain and Fair Use.

The experience of New Haven’s silversmiths illustrates the fluid nature of their craft in the 18th century. New York silversmith Cornelius Kierstede came to New Haven in 1729, attracted by a silver mine he rented nearby. Soon, local silversmiths offered competition. Guilford native Ebenezer Chittenden worked in Madison and New Haven. Chittenden trained Abel Buell, a Killingworth native who pursued a variety of engraving and metalworking trades in New Haven. Buell made Connecticut’s first pennies. He trained Samuel Shethar, but both fled to Florida in 1774 to avoid the hostilities that led to the Revolutionary War. Shethar returned to Connecticut to work in Litchfield, where the economy boomed after the war. Like other silversmiths at the end of the 18th century, Shethar formed a partnership to expand his operations, first with Isaac Thompson in Litchfield and, after 1806, with Richard Gorham in New Haven.

In the early 19th century, machine-aided processes that enabled manufacturers to produce higher quantities at lower cost than handcrafted work transformed the silversmiths’ business. The new process for electroplated silver wares produced highly decorative and relatively inexpensive goods that dominated the market by mid-century. By the end of the 19th century, Connecticut’s silver industry was concentrated in the conglomerate International Silver Company formed in 1898 and later headquartered in Meriden.

Flask attributed to the Coventry Glass Works – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain and Fair Use.

Glass: From a Business Monopoly to a Competitive Industry

Recognizing the importance of glass production, the Connecticut General Assembly awarded the Pitkin family a 25-year monopoly for glass manufacturing in 1783. The Pitkin Glassworks, in business in Manchester (then East Hartford) until 1830, made window glass and glass for clock cases and other uses but primarily concentrated on producing bottles and tableware, including pitchers, creamers, and bowls. They imported sand from New Jersey to make the glass and shipped large bottles called demijohns to the West Indies for the rum trade. While many of the bottles were blown with patterns of ribs and swirls in green and other earth-tone colors, distinctive molded flasks for spirits and inkwells are among the most recognizable of the firm’s products today.

Redware jar attributed to the Day Pottery – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain and Fair Use.

Connecticut’s glasshouses flourished after the Pitkin monopoly expired. The Coventry Glassworks (1815-1848) and West Willington Glassworks (1814-1872) also produced large quantities of bottles, inkwells, tableware, and jars. Later, entrepreneurs established a series of glasshouses in New London and Westford, where they made jars, soda bottles, medicine bottles, and other commercial wares.

Ceramics

Connecticut potters produced “redware,” a reddish-brown utilitarian pottery made from local clays that they formed into bottles, pie dishes, and shallow pans for cooling milk. Some potteries also produced “stoneware,” a harder, grey pottery that required special clay. Stoneware was often formed into crocks for storing preserved foods and jugs for storing liquids. Finer grade ceramics, like porcelains, were imported.

The States family, Dutch immigrants from New Jersey, established some of Connecticut’s earliest potteries. They opened shops in Greenwich in 1750 and in Norwich in 1769, both making stoneware with clays imported from New Jersey. Redware potters were busy across the colony by the middle of the 18th century: in Goshen and Litchfield by 1750; in South Woodstock by 1785; West Hartford by 1790; and South Norwalk by 1800. There were nine potteries in Hartford County in 1810. These potteries served a wider area than their own towns. A pottery in Pomfret, for example, was producing 5,000 pieces, including 2,000 milk pans, in 6 firings over a single summer at the end of the 1700s.

Among Connecticut’s best known potters were the Seymour and Goodwin firm active in Hartford before 1800. Other prominent firms included Hervey Brooks, active in Goshen between 1822 and 1860 (his pottery shop is now installed at Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts), and the Smith and Day pottery of Norwalk, which operated for nearly a century, in one form or another, beginning in 1793.

Needlework and Textiles: A Window into Women’s History

Textiles, including bedding, towels, carpets, and clothing, were among the most valuable items in the 18th-century household. Largely produced by women and girls at home, these fabrics document the industry and aspirations of their makers.

Samplers and needlework, often identifying particular girls and places, were popular after the Revolutionary War. With stitched alphabets, pious verses, and decorative motifs, they demonstrated the maker’s accomplishments and provided her with a model for marking and embellishing the household textiles she was expected to produce for her own home. These textiles could include utilitarian fabrics and the more elaborate stitched seat covers and pocketbooks for men and women.

The First, Second, and Last Scene of Mortality embroidered by Prudence Punderson – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain and Fair Use.

Girls from wealthier homes were frequently sent to schools where they learned more decorative needlework, such as stitching allegorical scenes in silk threads on satin. A group of ambitious samplers and canvas works from the Norwich area done between 1740 and 1770 indicates the presence of such a school there or in nearby Rhode Island. In Hartford, the Misses Patten and Mrs. Lydia Royse operated schools from 1785 to 1825 and from 1799 to 1818, respectively. Sarah Pierce ran a school in Litchfield from 1792 to 1833.

Perhaps the best-known Connecticut needlework is the silk embroidery The First, Second and Last Scene of Mortality by Preston’s Prudence Punderson, the daughter of a prosperous Tory. The detailed scene depicts the cycles of a woman’s life presented in an 18th-century room interior.

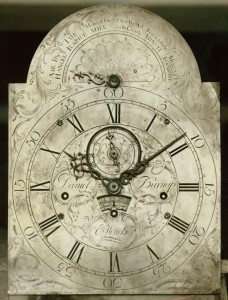

Clock works by Daniel Burnap – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

Clocks: From Craft to Mass Manufacturing

Connecticut’s clock-makers established a thriving business throughout the 18th century, with a number of makers working across the state, producing brass-works clocks by hand to be placed in tall cases.

The transition from craft to manufacturing is well-illustrated in clock-making in Connecticut. By 1773 English immigrant Thomas Harland settled in Norwich, where he made clocks and watches. A prolific craftsman, he is believed to have produced as many as 25 clocks a year. Among his numerous apprentices was Daniel Burnap, who opened a shop in East Windsor before 1786. When he retired to his farm in Coventry, Burnap’s business was diverse: he made brass hardware, surveyors’ instruments, jewelry, and buckles in addition to clocks. He also had trained many apprentices, including Eli Terry.

Meanwhile, Hartford’s Benjamin Cheney began making clocks with wooden movements, which were cheaper than brass-works clocks, though less reliable. Eli Terry studied with Cheney or his brother (which brother he studied with is not yet known) in addition to his apprenticeship with Burnap. Setting up shop in Plymouth, Connecticut, in 1793, Terry was an inventive mechanic, creating new mechanisms and methods. He is credited with transforming clock-making from handcraft to manufacturing with water-powered machines. By 1810, he was able to produce 3,000 clocks in a year.

Manufactured clocks and watches became an important industry in Connecticut in the 19th century centered in Waterbury, Bristol, Thomaston, and New Haven.

Collectors and Antiques

As mass-produced goods for national markets replaced handcrafted furnishings in the 19th century, a new appreciation for old-style “colonial” furnishings emerged. Known as the Colonial Revival movement, this national interest in American antiques was led by a group of Connecticut collectors including Irving Lyon and Henry Erving, both of Hartford, their friend George Dudley Seymour of New Haven, and Luke Vincent Lockwood of Riverside.

Wallace Nutting popularized and romanticized American antiques from his Southbury home between 1905 and 1912. He published sentimental photos of American interiors furnished with antiques and produced a line of reproduction antique furniture.

The antiques business has been active in Connecticut throughout the 20th century, with major American dealers located in the state. In the late 1960s, The Newtown Bee began publishing Antiques and the Arts Weekly and became a national presence in the market.

Contemporary Decorative Arts

Hand-crafted decorative arts continue to be made across the state, with nationally recognized makers working in Connecticut studios. These activities are often showcased and taught at the state’s contemporary craft centers, including the Brookfield Craft Center (established in 1954), the Farmington Valley Arts Center in Avon (1974), the Creative Arts Workshop in New Haven (1961), Wesleyan Potters in Middletown (1948), and the Guilford Handcraft Center (1962).

Ann Y. Smith, a museum director and curator working in Connecticut for 30 years, is a writer and public speaker specializing in the state’s cultural history.