By Leah S. Glaser

In 2011, an unusual October snowstorm followed Hurricane Irene and knocked out electrical power across Connecticut for days. The Hartford Courant headlined, “Connecticut’s Love of Trees Threatens Electrical Service” and characterized the Governor’s tree-trimming plans as a “War on Trees.” “Mark my word,” warned Governor Dannel Malloy, “when we start to do that… there are going to be people wrapping themselves around trees.” But most citizens living without electricity hated the power company and the trees by that point. They had inherited a history of state policy balancing economic development with the nurturing and protection of natural resources.

Conservation and development seem like opposing inclinations, but Connecticut residents have redefined this complex relationship over time and influenced our nation’s perception of it as well. In 1910, the first chief of the United States Forest Service, Gifford Pinchot of Simsbury, asserted that, “The first principle of conservation is development, the use of natural resources now existing on this continent for the benefit of the people who live here now. There may be just as much waste in neglecting the development and use of certain natural resources as there is in their destruction.”

Early Land-use Practices

Cultural values and behaviors determine how people develop natural resources. Prior to colonization, Native communities learned to accommodate the seasonal cycles of New England’s ecosystem by moving about the region to farm and hunt. Larger tribes tended to have a greater impact on the land, yet their farming practices somewhat reduced stress on the landscape. They rotated crops, rarely broke up all the soil over a field, and abandoned lands after several years rather than re- fertilizing. In order to clear new land for cultivation, some burned forests.

European colonists arriving in the Connecticut River Valley brought a different culture, one that placed a high value on permanent settlement and individual land ownership. Perceiving a landscape abundant in resources, the newcomers enlisted lumber and fur for mercantile use, targeting and nearly eliminating several native species. Agricultural settlement soon displaced the fur trade. By the mid-17th century, households cleared inland trees for farmland but also freely consumed about an acre of forest a year for shelter, furnishings, clothes, and fuel, often in open fireplaces. Forest clearing increased flooding and altered stream flows, creating droughts in other areas. Without leaves to catch rainfall, swampy conditions attracted mosquitoes and subsequently produced diseases like malaria. By the 19th century, settlers had cleared two-thirds of the state’s acreage and drastically reduced animal populations. Unlike the seasonal hunting and gathering cycles observed by the region’s indigenous groups, livestock and domestic animal-raising required controls, such as pasturing, fencing, and hunting predatory species. Restricted to the least desirable of agricultural lands, Native communities grew more densely populated and sedentary, diseases spread faster, and many abandoned cyclical subsistence practices. At the same time, colonists’ communities increased in number and size, they turned to commercial and industrial livelihoods.

The Impact of Industry and Urbanization

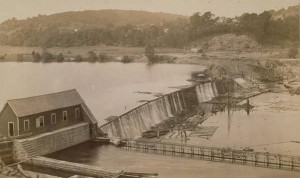

Housatonic Lake and Dam, Shelton and Derby, ca. 1894 – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain.

Throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries, Connecticut’s waterways attracted industries. Water provided transportation and power for grist and fulling mills, sawmills, tanneries, and iron furnaces. Later in 1909, the emerging Connecticut Light and Power Company harnessed four major waterpower sites on the Housatonic River to generate electricity. Such industries built dams to divert and store water, but they helped deplete forest acreage for their facilities and operations until such enterprises moved west. Competition from western territories, foreign trade, and urban manufacturing jobs drew the population away from Connecticut’s rural agriculture by the end of the 19th century.

Urbanization and industrialization polarized attitudes toward land use. Motorized transportation, suburbanization, and utility services further stressed Connecticut’s environment. Between 1850 and 1900, cultivated land in Connecticut fell from 73% to only 46%. Those who did farm used land intensely, planting orchards and grains for the urban population. Many enlisted new technologies, like locally-made cast-iron plows, harvesting equipment, and mowers to cultivate greater tracts of land. Others, like Samuel W. Johnson of Yale and Theodore S. Gold of Cornwall, encouraged principles of scientific agriculture to alleviate soil erosion. These men developed programs through schools like the Cream Hill Agricultural School, Yale, and the Storrs Agricultural School (later the University of Connecticut). They also helped to form agricultural organizations and the state established a Board of Agriculture in 1866. Land-grant universities with research centers also established Agricultural Experiment Stations in Middletown (Wesleyan University), New Haven, and Storrs.

Beyond agriculture, oystering and housing construction along the shoreline in the early 1900s altered other ecologies. Sewage and industrial waste from almost every Connecticut town flowed into rivers and then into Long Island Sound. Meanwhile, uncontrolled fire and sawmilling decimated the forests by the peak of lumber production in 1909. Blight wiped out acres of chestnut trees. Some abandoned agricultural fields were regenerating woodland, but concerned citizens feared for Connecticut as it lost valuable natural resources.

Nostalgia for Vanishing Wilderness Promotes Preservation

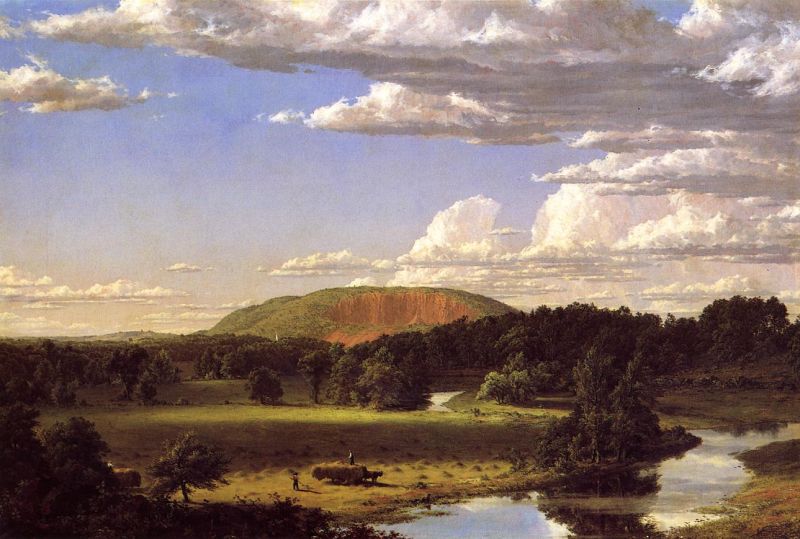

Frederic E. Church, West Rock, 1849, oil on canvas – New Britain Museum of American Art. Used through Public Domain.

Rapid western expansion combined with industrialization and urbanization in the Northeast ignited nostalgia for nature and loss of a perceived “pristine wilderness.” Artist Frederic Church of Hartford, a founder of the Hudson River School of landscape painters who built public appreciation of natural landscapes in their depictions of vast fields and vistas, majestic mountains, and calming lakes and streams, illustrated the West as well as the New England countryside in paintings such as West Rock, New Haven (1849). These images, as well as the writings of fellow New Englander Henry David Thoreau, convinced many Americans that nature was essential to man’s physical and spiritual health and ultimately spurred the government to establish its first preserve in Yellowstone National Park in 1878. In 1881, the Department of Agriculture created a division of forestry (later the US Forest Service). Locally, cities looked to set aside nature for its urban workers. In the 1870s, architect Frederick Law Olmsted, who designed New York City’s Central Park, began work on Walnut Hill Park in New Britain. Influenced by Church and others, Olmsted advocated the park as a naturalistic landscape, an aesthetically designed, man-made wilderness where urban residents could escape the harsh realities of industrial work without losing the comforts of the city. These ideas can be seen in Bushnell Park and the rest of Hartford’s extensive park system.

A small but influential number of Connecticut residents led state conservation policies. In 1869, Connecticut’s legislature allowed each town two fish wardens. It later created enforcement positions at the county level as well, until the state appointed game wardens. In 1895, Reverend Horace Winslow of Simsbury called the first meeting of the Connecticut Forest Association, later called the Connecticut Forest & Park Association (CFPA), to advocate the preservation, restoration, and scientific maintenance of forests. In 1901, they lobbied the state’s General Assembly to develop forest policy, reforest “barren lands,” appoint a state forester and town tree wardens, and use state funds to purchase land for the establishment of state forests. Connecticut was the first state to establish a State Forester (Walter Mulford). The state forester coordinated efforts to control forest fires with research and advocacy duties from the Agricultural Station in New Haven. By the mid-20th century, the state designated its game wardens as “conservation officers,” tasking them with educating private landowners through education and research.

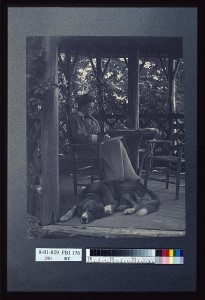

Mabel Osgood Wright, circa 1900 – By James Osborne Wright. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Used through Public Domain.

In 1898, a Connecticut landscape writer and Fairfield resident, Mabel Osgood Wright, founded the Connecticut Audubon Association, one of the first state chapters, and in 1914 established Birdcraft, the first private songbird sanctuary in the country. Senator George McLean of Connecticut worked to pass the Migratory Bird Act of 1913, which placed the protection of those birds out of state control and into federal oversight. At the same time, a wealthy young Litchfield man, Alain Campbell White, established the White Memorial Foundation and began buying large parcels of land; he set aside 4,000 acres for a natural preserve and, together with Jessie Gerard of New Haven, proposed the establishment of a state forest. The assembly eventually designated the Peoples State Forest in Barkhamsted out of White’s donation. The state responded by creating a Commission in 1913 to acquire and maintain open spaces, particularly along the shoreline, for “the preservation of natural beauty and historic association” as well as recreation.

Progressive Era Balances Managed Use and Public Benefit

On a national level, Sierra Club founder and wilderness preservation advocate John Muir guided such conservation activities, but his ideas collided with the Progressive Era, a time when the proliferation of technology spurred an industrial economy. Reformers protested against corruption and the consolidation of wealth, which compromised the values of equality in the United States. For many, like Simsbury’s Gifford Pinchot, this imbalanced allocation of resources included natural resources. Pinchot found a like mind in President Theodore Roosevelt, a well-known supporter of progressive reforms. Both embraced a conservationist philosophy that discouraged waste and advocated the scientifically planned development of natural resources for the benefit of the public good—a good often defined in economic terms.

Pinchot, who served as the Chief of the US Forest Service from 1898-1910, co-founded the Yale University School of Forestry in 1900, the first of its kind in the country. Famous alumni of Yale’s School of Forestry include Aldo Leopold, who pioneered studies in the field of ecology, and Dean Henry Graves, who succeeded Pinchot as US Forest Service Chief. Yale agreed to provide office space for the expanded Connecticut Forest and Park Association between 1906 and 1927, and this private-public relationship launched many of Connecticut’s—and the nation’s—conservation efforts from New Haven.

Signs of Changes to Come

Devil’s Hopyard, East Haddam, ca. 1900 – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain.

The history of conservation and development in Connecticut up until the 1920s reveals that our present “War on Trees”—as well as calls to defend them—has been an ongoing one.

In times past, the trees gained allies as people moved from farms to city work. Urban development visibly strained the state’s natural resources and prominent, concerned citizens found ways to set aside certain places for preservation without significant opposition.

Into the 1920s, some of the nation’s most prominent foresters and conservationists, particularly Gifford Pinchot, Henry Graves, and their protégé, longtime Connecticut State forester and Yale alumni Austin Hawes, influenced the design of an administrative structure for managing the state’s natural resources in both forests and parks within the conservationist philosophy of managed use and public benefit. Those preserves were, ironically, not primarily for preservation and recreation but for conservation (protection, controlled development, and equitable economic use). However, the demand for parks outside of the growing cities increased. People wanted large areas for recreation that would be protected from any development and accessible by the new motor transportation and expanded roads. Those desires would challenge the conservationists’ approaches to managing large acres of forests, their watersheds, and undeveloped, open spaces in Connecticut.

Leah S. Glaser, PhD, is an Associate Professor of History at Central Connecticut State University where she teaches courses on Public History and the American West.