By Doe Boyle

The Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica), designated as the state shellfish in 1989, is a bivalve mollusk that grows naturally in Connecticut’s tidal rivers and coastal bays and is cultivated in seeded beds in Long Island Sound by oyster farmers. Oysters, long a favored and dependable food source of the area’s native peoples, also became a diet staple of early European settlers, who quickly learned how to cultivate and harvest oysters from the Long Island Sound.

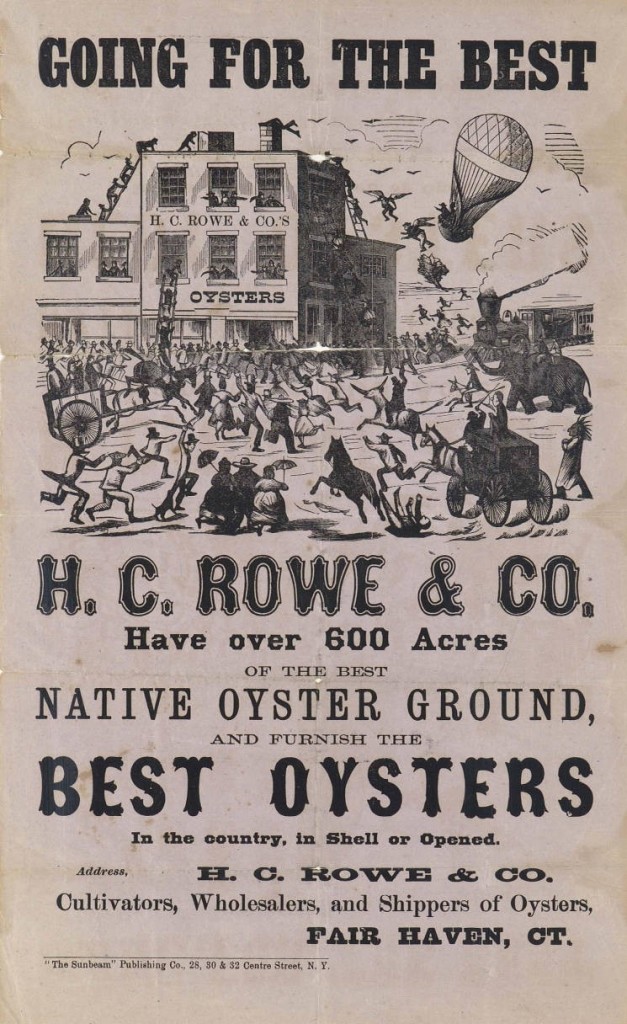

Going for the best: H.C. Rowe & Co. have over 600 acres of the best native oyster ground, and furnish the best oysters in the … Fair Haven, Ct. Broadsides, circa 1880 to 1889 – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain.

Early Oystering Leads to Fishing Laws

During the colonial period, many Connecticut fishermen began to focus their labors exclusively on the collection of wild, or naturally occurring, oysters. This activity triggered a depletion of the natural beds and threatened the existence of the species in local waters. In the early 18th century the first colonial laws regulating the taking of oysters in Connecticut waters appeared, and some of the earliest town records (in Stonington and Groton, for instance) relate to the separation and designation of individually parceled oyster grounds.

In about 1750, the General Assembly voted to permit shore towns to enact bylaws regulating the taking of shellfish in each town’s adjoining waters. In 1762, a law passed at a New Haven town meeting prohibited oystering during the spawning months from May through August to allow oysters time to mature and reproduce. In 1766, the use of “draggs” (bottom-scraping dredges) was outlawed to further protect the natural beds.

Demand for Shellfish Creates Need for Importation

Unfortunately, the laws that had been intended to protect the beds failed to stop overfishing in southern Connecticut. Before oyster cultivation began in local waters, shortages of “natural growthers” led some oystermen to buy their “catch” in New York, the Delaware Bay, and the Chesapeake Bay. As John M. Kochiss notes in Oystering from New York to Boston (1974), “the commerce in oysters from the Chesapeake…was confined in Connecticut almost exclusively to New Haven, where the largest oyster shops were located.”

Indeed, as reported by Ernest Ingersoll in his 1881 volume, The Oyster Industry: Tenth Census of the United States, 250 schooners imported 2 million bushels of oysters to New Haven’s Fair Haven oyster shops in 1858. These Fair Haven oysters were then shipped inland to such cities as St. Louis and Chicago. By the 1890s, the world’s largest fleet of oyster steamships operated in Connecticut.

Connecticut Oystermen Learn to Cultivate

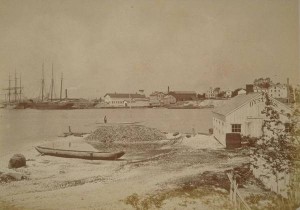

An oyster house on the New Haven shoreline, 1872 – Mystic Seaport Museum. Used through Public Domain.

Town records of early colonists in Groton indicate that some oystermen experimented with cultivation. Groton oystermen bent branches into the water to attract oyster larvae, which would then “set” on the twigs and grow to edible size. For the most part, however, oyster-bed cultivation was unknown in the United States until the 1820s, when the creation of artificial beds began in earnest. Connecticut oystermen gathered the free-swimming oyster larvae, planted them on artificially created beds of oyster shells and raised them to maturity. By the late 19th century, oyster cultivation in the state had developed into a major industry.

In the 1800s, oystering boomed in New Haven, Bridgeport, and Norwalk and claimed modest success in other towns along the Connecticut shore. By the mid-19th century, Connecticut led oyster seed production north of New Jersey. Famed as robust, select oysters of consistent size, with deeply cupped shells and fat meats with a flavorful saltiness, Long Island Sound’s Bluepoint, Saddle Rock, and Great White oysters were known far and wide. In 1911, Connecticut’s oyster production reached its peak at nearly 25 million pounds of oyster meats—higher by far than producers in New York, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts.

Threats to the Oyster and the Oyster Industry in the 20th Century

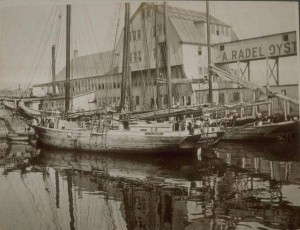

Schooner in front of Radel Oyster Co., South Norwalk, early 1900s – Mystic Seaport Museum. Used through Public Domain and fair use.

Increases in the coastal human population, industrialization, pollution, and marine traffic, as well as continued overfishing, threatened Connecticut’s oyster beds after 1920, with production falling drastically after 1950. Predation by such creatures as oyster drills (a snail), black drum (a fish), crabs, and sea stars decreased yield, as did destruction of beds by severe storms, increased amounts of silt, and channel dredging.

Market demand for oysters from 1890 to 1940 also faltered because of economic depressions and because consumers discovered that oysters could contain pathogens. Later in the 20th century, a spike in water temperatures and the resulting bloom of naturally occurring parasites destroyed 80-90% of the state’s oysters, particularly in 1997 and 1998.

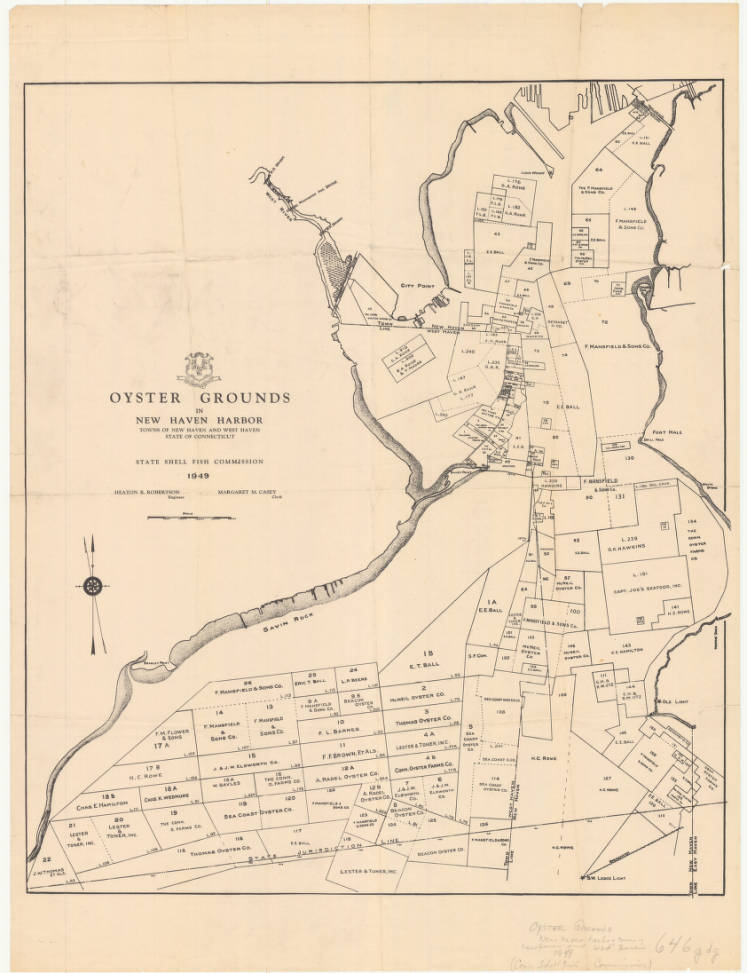

Oyster grounds in New Haven Harbor, from the State Shell Fish Commission, 1949 – Mystic Seaport Museum. Used through Fair Use.

Aquaculture and the Return of the Oyster

Today, marine biologists are breeding hardier parasite-resistant oysters. Connecticut aquaculture—the farming of aquatic plants and animals—includes renewed oyster-growing operations on underwater leases in Long Island Sound. At the outset of the 21st century aquaculture became one of the country’s fastest growing agricultural industries, and, for Connecticut, oyster farming accounted for its lead in aquaculture production in the Northeast.

In the process of oyster farming, very young oysters are spawned in a land-based or offshore hatchery, moved to a protected off-bottom, floating-dock nursery system where seed oysters grow in mesh bags or cages, and then returned to artificial clean-shell beds for the completion of their growth to market-size oysters. These artificial oyster beds have the same environmental benefits as natural beds, and the oysters that grow under these techniques generally reach a bigger size, have fleshier meats and are better shaped than “natural set” oysters. Among the actively managed beds in coastal Connecticut are those in the Mystic area, New Haven, Bridgeport, and Norwalk.

In the 21st century, Connecticut’s oyster industry is enjoying a slow but steady renaissance. In the year 2008, for instance, more than 160,000 100-count bags of Connecticut-grown oysters, worth well more than $6 million, were marketed throughout the country. Renowned for their quality and flavor, Connecticut oysters, restored by nature and by careful regulation and advanced techniques in aquaculture, seem destined for continued economic importance.

Doe Boyle, a Connecticut Office of the Arts Master Teaching Artist of creative and expository writing, is an editor, a widely published freelance writer, and the author of 11 children’s books and 2 travel guides to Connecticut, her home state.