By Leah S. Glaser

For centuries, Connecticut residents have reflected and influenced how our nation has balanced natural resource conservation and economic development. Prior to the 20th century, urban development visibly strained the state’s natural resources and prominent, concerned citizens found ways to set aside certain places for preservation without significant opposition. The recreational demands of the 1920s further shifted Connecticut’s conservation efforts from private activism to public responsibility. Unlike management at the national level, where different Departments, that of Agriculture and the Interior, respectively, administered the forests and parks, Connecticut developed a single body for oversight of its natural and historic resources.

Campbell Falls State Park, Norfolk – Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries

In 1921, the State Park Commission became the State Park and Forest Commission and assumed responsibility for appointing the State Forester, a position that had previously included duties at the Agricultural Station at New Haven. Thus, Connecticut’s park and forest systems, which both addressed recreational needs, operated interdependently. The Commission allowed the state forester, Austin Hawes, to practice scientific forestry for economic development, while a superintendent managed the parks for aesthetic and recreational enjoyment. Field Secretary Albert Turner, charged with acquiring state parklands, agreed that forests and parks were different in purpose and management. Turner further separated state parks from the formal, “museum-like” municipal parks.

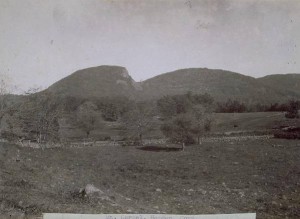

Sleeping Giant, Mount Carmel, Hamden, ca. 1890-1908 – Connecticut Historical Society

To Turner’s dismay, Connecticut’s acquisitions of land for public parks in a state dominated by privately-held property lagged behind similar efforts in neighboring states. Still, the state park system grew to 7,000 acres including Hammonasset Beach in Madison, Macedonia Brook and Kent Falls State Parks in Kent County, Mohawk Mountain State Park in Cornwall County, and the Campbell Falls State Park in Norfolk and North Canaan. In some cases, private citizens’ groups worked to achieve state protection for valuable recreational sites. For example, the Sleeping Giant Park Association successfully lobbied to protect the Mount Carmel site against quarry operations through park designation. Similar local groups in Stamford (Laddin’s Rock) and Westport (Sherwood Island) worked with the Connecticut Forest & Park Association (CF&PA), a nonprofit, non-governmental group active since 1895, to establish conservation areas. Such partnerships brought the conservation-minded organization, which had previously focused on the preservation, restoration, and scientific maintenance of forests, into the realm of recreational development.

Depression-era Programs Advance Conservation Projects

The Depression provided additional opportunity for state conservation efforts through the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), initiated in 1933 and one of the flagship work programs of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. In fact, work camps developed in Connecticut by State Forester Hawes from 1930-32 served as prototypes for the national CCC program. The need for such work was pressing. The Connecticut River flood in 1936 and the Great Hurricane of ’38 devastated vast parts of a landscape already scarred by decades of industrialization and deforestation.

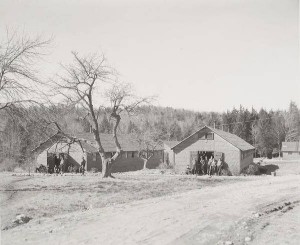

Civilian Conservation Corps work camp, located in the Tunxis State Forest, East Hartland, 1935 – Connecticut State Library, Mills Photograph Collection of Connecticut, 1895-1955 (PG 180)

In all, Connecticut hosted 21 CCC camps both to revive the forests and to meet the public’s demand for recreational opportunities. The young men built hundreds of miles of hiking trails, access roads, sawmills, dams, picnic areas, swimming ponds, and fire towers throughout the forests, many revived through planting and the latest scientific reforestation techniques. Their work built entrances and traffic rotaries at Hammonasset Beach, the ski trails at Mohawk Mountain in Cornwall, and the Schreeder Pond swimming complex at Chatfield Hollow State Park in Killingworth. In addition to creating accessible preserves, Connecticut’s CCC helped the state revive a commercial forest products’ business by helping to build wood treatment plants, charcoal kilns, and a state sawmill. They even harvested ice from state forest ponds for commercial sale. The CCC also developed a state trail system, passing through public and some private lands, with miles of hiking, bridle, and ski trails marked by blue paint (the Connecticut Blue Blazed Trail System, now 700 miles).

All of this activity further confused the role of forests and parks in a rapidly industrializing state. Opposing philosophies of nature—one advocating carefully managed resource use and the other promoting preservation and recreation—inevitably encountered conflicts. Connecticut Governor, and later Senator, George McLean willed 3,400 acres for the McLean Game Refuge in 1933 to serve as a public “wilderness recreation” area. McLean’s idealistic wishes challenged the ecological practicality of preserving wilderness alongside agricultural and recreational uses. The state chapter of The Nature Conservancy eventually devised a plan that divided the refuge to accommodate wildlife and vegetation management needs with public use.

Furthermore, CF&PA and other private organizations promoted the beautification of roadways with shade trees and helped establish the Bureau of Roadside Development in the State Highway Department. The construction of the Merritt Parkway in the 1930s equated transportation with recreation and conservation by luring drivers away from the commercial stress of the Boston Post Road and closer to nature with a winding scenic drive surrounded by an open, naturalistic landscape of fields and trees. It forecast a repurposing of Connecticut’s natural resources for use in urban development and recreation, rather than managing them as a local economic resource as urged by earlier conservationists. For example, when the Bridgeport Hydraulic Company hoped to impound water for the city, it took the private land of the former iron community of Valley Forge by eminent domain. The community fought the seizure in court with a broad and unlikely coalition of landowners, progressive urban reformers (including nationally-prominent Lillian Wald), garden clubs, and even the state’s socialist party. The water company prevailed, built the dam, and created the Saugatuck Reservoir. The reservoir has since become part of Centennial Watershed State Park (so named to honor the State Forest System’s 100th anniversary) and is part of the largest “natural” and recreational preserve of southwestern Connecticut.

Suburbanization and Modern Environmental Movement Bring Change

Not surprising for a state emerging from the Great Depression, the first State Development Commission in 1940 focused heavily on the protection of natural resources for economic development, with little regard for site preservation. But soon afterwards, a group of businessmen interested in the recreational development of Connecticut’s forests and parks took control over the state’s reorganized Park and Forest Commission and successfully challenged the foresters and conservationists who had controlled its policies and acquisitions for 30 years. The Commission’s professionally trained foresters protested the continued management of the forests and parks under a single park administrator (Hawes retired early) and with the same primary purpose: “public enjoyment.” World War II also slowed conservation efforts save for the acquisitions of what became Gillette Castle State Park and Nathan Hale State Forest.

Landscape blight, New Haven, ca. 1950s – New Haven Museum

By the 1950s, Connecticut was the fourth most densely populated state, with 3 million people residing within 5,000 square miles. Single-story retail stores, vast parking lots, and larger house lots had eliminated much open land space. Policymakers began to worry about the dispersed residency that suburbanization caused, making health, utility, transportation, education, and other public services increasingly impractical, logistically difficult, and financially unfeasible. In 1959, Connecticut consolidated related agencies and established a Commissioner of Agriculture and Natural Resources, marking a more coordinated approach for planning development.

The environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s further encouraged Connecticut to rebalance its policies and administrative practices regarding conservation and development. The state formed committees to gather data for future soil and water needs and designated 27 “natural areas” free of human interference (beyond trails) in order to serve scientific, educational, and cultural purposes. Population pressures prompted more towns to adopt planning and zoning commissions as well as ordinances to control and coordinate land use—although some, like New Haven, already had well established planning departments. At the same time, private advocacy groups like the CF&PA repeatedly protested power development along the Connecticut River and highway construction into the state forests. In 1965, such groups stopped I-91 from running through East Rock Park in New Haven. State laws and tax concessions encouraged maintenance of open space and the development of outdoor recreational facilities. Towns like Madison and Ridgefield founded land trusts that advocated for clean air, protection of water resources, and open space. On the heels of the National Environmental Protection Act, and faced with new environmental problems, the state created a coordinating agency for all natural resource and environmental problems in the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) in 1971.

Legislation Tackles Water Quality and Other Issues

In 1973, the legislature passed the Connecticut Environmental Protection Act, which required state agencies to evaluate the ramifications of any action that might have an impact on the environment. The first statewide Conservation and Development Report, in 1974, urged greater attention to water supply issues, natural and historic preservation principles, scientific forest management, investment and development of public recreational areas along the shoreline, planning higher density and mixed-use development, and a stronger partnership on these issues between state and local governments. It divided the state into different zones of use (urban, open space, recreation, etc).

However, the plan threatened the local autonomy of Connecticut towns and lacked details about the state’s role in its implementation. As a result, a revised report the following year incorporated extensive public comment, more details about implementation and state-local coordination, and more complex categories for land use.

Concerns about water pollution encouraged the state legislature to pass Connecticut’s Clean Water Act in 1967. The act, which was ahead of national policy, raised water quality standards and the level of sewage and wastewater treatment. For example, a state grant program extended sewer services to 63% of the population. In 1986, the Connecticut Clean Water Fund (CWF) provided financial assistance to towns and cities to design and construct wastewater collection and treatment projects. In the 1980s, the Federal Environmental Protection Agency’s plan to study the water quality of Long Island Sound prompted a shift in understanding the Sound’s development as an ecological region, rather than merely an economic and political zone; this helped launch efforts to restore the Sound. However, a thriving economy and housing boom proved to be formidable foes to conservation efforts.

As federal legislation required more sophisticated water treatment technology, towns and utilities no longer needed vast watersheds to ensure potable water quality. These entities then sold the land to developers. In the 1990s, actor and state resident Paul Newman led a successful protest against selling the Trout River Valley, a 700-acre tract of watershed no longer needed to ensure the quality of the water supply. A rare victory for open land advocates, the watershed’s preservation symbolized how the housing boom of the late 1990s and early 2000s challenged conservation efforts particularly in the area of open space.

East Haddam Bridge over the Connecticut River – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Carol M. Highsmith Archive

Additional private statewide and local advocacy groups have emerged since the 1970s that reflect broad and diverse coalitions of government agencies, philanthropists, and volunteers. In 1997, for example, the Connecticut River Watershed Council and 49 other sponsors successfully nominated the Connecticut River as an American Heritage River, and the Lower Farmington River and Salmon Brook are currently undergoing Wild and Scenic River designation by the National Park Service. Organizations such as the Rivers Alliance of Connecticut, The Face of Connecticut Campaign, and the 1000 Friends promote regional planning and environmentally sensitive development. Other groups undertaking conservation work in the state include the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation and the Mohegan Tribe. In conjunction with the Federal Environmental Protection Agency’s Tribal Program, the Mashantucket Pequots maintain a Natural Resource Protection Department responsible for preserving the reservation’s ecosystems. The Mohegans conserve energy through fuel cell technology and practice waste reclamation and recycling at their casinos, most notably in the area of food service.

Looking to History for a Way Forward

The 21st century raised new concerns about environmental and economic sustainability. Climate change, carbon emissions, and the effects of acid rain forced the state to integrate issues of conservation and development in new ways. Legislation required the state to draft plans of conservation and development every 5 years, and every 10 years for many towns, in order to receive state funding. Connecticut legislators passed bills on sustainable forestry (forest cover is now twice that of the 1700s), wetlands, drinking water, invasive plant and animal species, historic preservation, and farmland preservation. This included the bipartisan Community Investment Act in 2005, a national model for development legislation, which provides a revenue stream, through a recording fee on all municipal land transactions, for historic preservation, affordable housing, open land protection, and farmland preservation.

The Conservation and Development Policies Plan for Connecticut, 2005-2010 adhered to six Growth Management Principles that included redeveloping and revitalizing regional centers and areas with existing or currently planned physical infrastructure, environmental and open space conservation areas, and integrated planning on state, regional, and local levels. However, the housing market imploded in 2008 and stalled new construction projects. The current 2013-2018 plan continues the same “smart growth” philosophies with expanded, high density, mixed-income housing choices, cultural resource preservation, and concern for environmentally-related health issues. Rural land and “natural infrastructure” conservation (of ecosystems) is the closest the plan comes to integrating natural resource management with economic growth as the state’s earlier conservationists advocated.

The economic recession and the fall 2011 storms should compel us to look at past decisions regarding resource management. Some have been in step with national developments: Connecticut’s industrial economy grew with the country’s westward expansion, and its state park and forest program emerged alongside the US Forest Service and the National Park Service. But with much of Connecticut’s land privately owned, the balance between private development and the public good that the utilitarian, arguably overzealous philosophy of Connecticut’s early conservationists promoted proved precarious. Post-war housing and commercial building, the proliferation of the automobile, and demand for local leisure opportunities positioned conservation efforts as the foe, rather than a partner, of development. Examining this complex history may allow us to craft truly sustainable policies for the economy and the environment.

Leah Glaser, PhD is an Associate Professor of History at Central Connecticut State University where she teaches courses on Public History and the American West.