By Paul Grant-Costa

Once a common sight in Connecticut’s towns, itinerant Indian crafters walked miles across the state, selling all sorts of brooms, baskets, herbs, and other Native goods. In the late 18th century, several such vendors were known to the people of Guilford as town residents.

Dutch map (detail) showing the early 17th Century Quinnipiac (as Quyropey) territory: Nicolaas Visscher II (1649-1702), NOVI BELGII NOVAEQUE ANGLIAE NEC NON PARTIS VIRGINIAE TABULA, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, the Dutch National Library

Among them were Mantueese, his wife Hannah Punk (who lived to become a centenarian), and a blacksmith named Picket. Like many of his kinsmen, Picket was a French & Indian War veteran and served with a distinction — he single-handedly captured French General Dieskau at the Battle of Lake George in 1755.

A generation later, Oliver Momauguin, his wife Quinnetoket, and several other Native families returned seasonally to the east shore of New Haven to live among their relatives, sell their crafts, and work for local farmers. Having pursued a similar lifestyle, basket maker Asa Freeman eventually settled at Branford and died there in 1882.

These Indians share a common heritage. They are all Quinnipiac.

The Quinnipiac in Connecticut

Quinnipiac is a word that can be found today in, among other things, the title of a university, a national polling service, several businesses, and a bridge that crosses a river of the same name in New Haven, Connecticut.

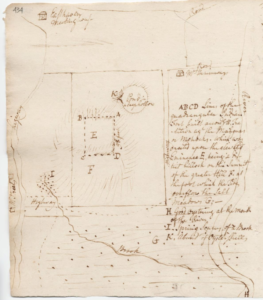

Ezra Stiles’ Description of the Indian Fort at East Haven, Connecticut, Itineraries 1: 454, Ezra Stiles Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

It was along this river estuary that a village of agricultural indigenous people existed for thousands of years. As do many tribal communities in New England, they draw their name from their homeland’s landscape. The Quinnipiac (meaning “people of the long water land” in the Quiripy language) and their ancestors inhabited what is presently the Quinnipiac River watershed in south central Connecticut, utilizing the environment’s resources on a seasonal basis.

The original Quinnipiac territory encompassed ten present-day towns in New Haven County, from the Atlantic shore at West Haven to twenty miles inland, from Woodbridge on the west to Madison on the east. In all, Quinnipiac Country extended over 300 square miles.

Its main village of Quinnipiac proper lay on both sides of the Quinnipiac River in what is now New Haven, North Haven, and East Haven. The metropole, as it does today, sat at the intersection of a number of important travel routes that ran along the shore and to other Indian communities in the interior. Intermarriage with neighboring tribal communities made the Quinnipiac kin to the Paugussett on the west, the Wangunk and Mattabesett on the north, and the Hammonasset and Niantic to the east. Quinnipiac deities Hobbomock and Keihtan provide the creation stories for the local landscape.

Population estimates for the tribe at the beginning of the 17th century are uncertain, but possibly over four thousand Indigenous men, women, and children lived within Quinnipiac homelands. That number declined by up to 90 percent after waves of smallpox epidemics, brought on by European contact, decimated Indian communities in southern New England in 1634 and 1635.

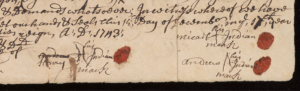

The Branford Congregational Church was the primary purchaser of Totoket land at Indian Neck. The image of the signatory marks of Micael, Andrew, and Henry (detail), Quinnipiac deed from Micael, Andrew, and Henrym Indians of Branford, to John Russell, Isaac Harrison, and Noah Rogers (1743), Gen Mss File 160, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection, Yale University

By 1638, the surviving Quinnipiacs lived at four distinct yet related villages along the Long Island Sound: Quinnipiac (New Haven), Monotwese (North Haven), Menunkatuck (Guilford), and Totoket (Branford).

Colonial Settlement Reaches Quinnipiac Territory

With the settlement of New Haven in 1638, colonial authorities began to acquire land along the Quinnipiac coast but reserved bounded space on which the surviving Indian communities could remain, creating America’s first Indian reservation.

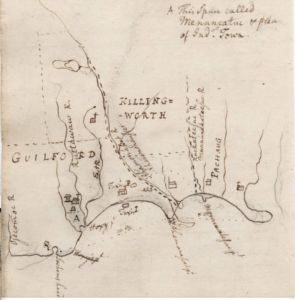

Ezra Stiles’ Map of Killingworth and Guilford, Connecticut showing Indian Town (marked A) Itineraries 1: 468, Ezra Stiles Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

As the colonial need for more land increased, tribal leaders and individual Quinnipiac landholders were pressured, or in some cases compelled, to sell their property, forcing Indian people to accommodate a greater colonial presence in their lives or to remove elsewhere.

After further land loss in the 18th century, some community members removed to a reservation created for them at East Mountain in Waterbury, or merged with the Paugussett, Schaghticoke, or the Tunxis in Farmington. Later migrations from Farmington to Oneida Country in New York and then to Wisconsin brought some families westward.

While this may have given the impression that the Quinnipiac had disappeared entirely, some community members remained in Connecticut, living less visibly in villages or moving to cities, where employment opportunities thrived. From the mid-18th century to at least the mid-19th century, a community of displaced Menunkatuck, Quinnipiac, Hammonasset, Niantic, Mohegan, and Wangunk coalesced at the West Pond section of Guilford. It was where Mantueese, Hannah, and Picket lived.

Quinnipiac landholdings may have been extinguished, but the Quinnipiac people have not been erased. While numerous descendants of the Quinnipiac still live in Connecticut and across the country, the community is not presently one of Connecticut’s recognized tribes, nor is it federally acknowledged. However, the Algonquian Confederacy of the Quinnipiac Tribal Council is an organization dedicated to preserving Quinnipiac history and culture.

Paul Grant-Costa is the Director and Executive Editor of the Native Northeast Research Collaborative (formerly the Yale Indian Papers Project).