By David Drury

The French and Indian War was the greatest military challenge faced by the Connecticut colony between the time of King Philip’s uprising and the American Revolution. The war had a profound impact on the colony because it severely taxed economic, political, and manpower resources and set in motion forces that caused Connecticut and Britain’s other original North American colonies to rise in rebellion a dozen years after the war ended.

Phillip [sic] alias Metacomet of Pokanoket. This print is a variant copy of a 1772 Paul Revere engraving – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Used through Public Domain.

In 1754, these two empires collided in what is now western Pennsylvania in a series of confrontations between French authorities and Virginia colonial scouting parties led by young George Washington. The following year, 1755, saw Connecticut authorities mobilize for war. In March, the General Assembly authorized bonuses and set salaries for military recruits. Three thousand enlistments followed and by June, hundreds of Connecticut militia had marched to Albany, which became the major staging area for the New York campaigns that followed. In July 1755, the war began in earnest when a Franco-Native American force routed British regulars and Virginia provincial troops on their way to oust the French from Fort Duquesne (present-day Pittsburgh).

Back in New York, Connecticut enlistees served as part of a planned move by General Sir William Johnson upon the strategic French outpost at Fort St. Frederic (Crown Point) along the southern end of Lake Champlain. Johnson’s expedition halted to construct a base of operations, Fort Edward, between the Hudson River and Lake George. The delay gave the French and their Native American allies time to launch their own attack. The forces clashed on September 8, 1755, in the Battle of Lake George.

Troubled Times for Connecticut Troops

Approximately eight hundred Connecticut troops under the command of Durham, Connecticut, native Phineas Lyman took part in the engagement, sustaining significant casualties: 45 dead, 20 wounded and 5 missing. These were in addition to a number of men who perished earlier in the summer from accidents and disease. It had been a rough introduction to military life. Many of the Connecticut troops, lacking effective weaponry and training, were employed in road-building, construction, and other menial tasks, and their morale did not improve when the wages promised by the General Assembly went unpaid.

By 1756, the conflict in North America had morphed into a world war with armies and naval forces engaged in Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean. Colonial legislatures in British North America responded to the Mother Country’s annual calls for manpower, and enlistments in Connecticut totaled about 3,700 for 1756 and 1757.

The war in North America continued to go badly for Britain, however. Fort William Henry, on the southern shore of Lake George, fell in August 1757 despite the presence of a substantial relief force holed up at Fort Edward just 15 miles away. Jabez Fitch Jr., a 20-year-old Norwich sergeant who was serving with a militia company from New London, kept a diary of life at Fort Edward during that time. Fitch expressed the impotence he and his fellows felt hearing William Henry under daily bombardment but unable to do anything about it: “The siege of Fort William Henry began August 3rd and it was surrendered the 9th at 7 in the morning. During the whole time of this siege our men were extreme resolute to go to relieve our people. But never could by any means get orders.” Fitch goes on to report the infamous massacre of William Henry captives by French commander Marquis de Montcalm’s Native American allies who, Fitch said, “plundered, stripped, killed and scalped our people.”

“Our treasury is exhausted, our substance consumed [and] the number of our able-bodied men much lessened,” Connecticut’s able colonial governor Thomas Fitch reported at the end of 1757. Also, he said, “the spirit, vigor and resolution” of the populace had much flagged. In short, the Connecticut colony was war-weary.

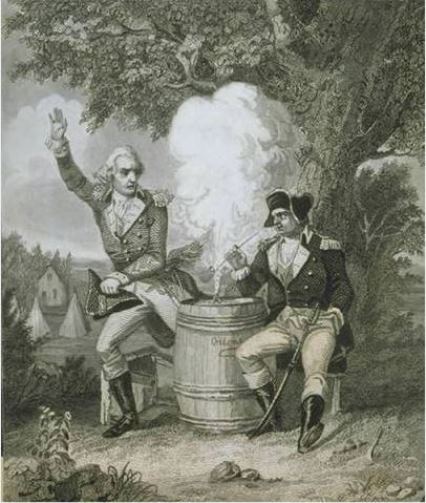

One of many legends surrounding Israel Putnam of Pomfret relates how, during the French and Indian War, an arrogant British officer challenged him to a duel. Print ca. 1850-1869 – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain.

Reinvigorated Efforts

The fortunes of war turned dramatically the following year, 1758. Under the leadership of William Pitt, the British government began pouring money and resources into the conflict, determined once and for all to establish naval and colonial superiority over France. In addition to dispatching more British regulars, Pitt asked the colonies for 20,000 provincial troops, pledging the British government’s assumption of the costs incurred to train, equip, arm, and pay them. The Connecticut General Assembly responded enthusiastically, declaring a levee of 5,000 in 1758 and another 5,000 in 1759. The colony came close to meeting both targets.

Major General Lyman’s newly reinvigorated Connecticut command formed a substantial portion of the army of 9,000 provincial troops and 6,000 regulars that British General James Abercromby employed in hopes of expelling the French from Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga), south of Lake Champlain. The ensuing battle on July 8, 1758, the biggest of the war in terms of forces involved and casualties sustained, was to be the last major French triumph.

Beginning with the fall of Fortress Louisbourg on July 27, 1758, British arms scored success after success, capturing Forts Duquesne, Niagara, and Carillon, Quebec City (September 1759), and finally Montreal (September 1760).

![Putnam [rescued by Molang], wood engraving by Lossing & Barritt, 1856 - New York Public Library Digital Gallery](https://connecticuthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/FrenchIndianPutnamRescued.jpg)

Putnam [rescued by Molang], wood engraving by Lossing & Barritt, 1856 – New York Public Library Digital Gallery. Used through Public Domain.

The Havana expedition marked one of the last episodes of the war, which concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in February 1763. The treaty left Canada and the vast Great Lakes region under British control. New France was no more.

The War’s Lasting Consequences

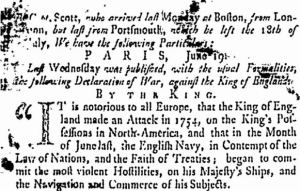

Detail of the news from “Paris, June 19”, The Connecticut Gazette, September 18, 1756, New Haven, Connecticut – Used through Public Domain.

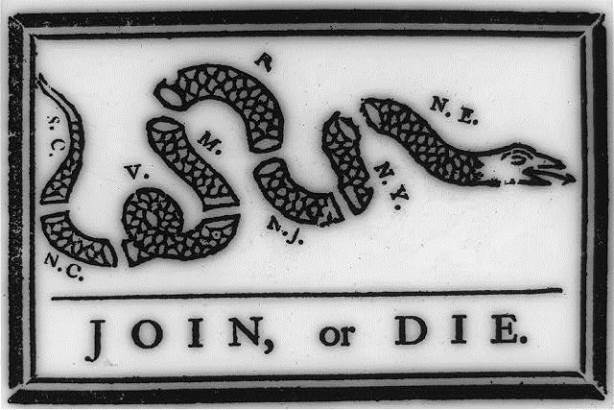

The French & Indian War made a deep impression on the Connecticut colony. Its first newspaper, the Connecticut Gazette, launched in April 1755 in New Haven largely to provide readers with reports about the conflict. A second newspaper, the New London Summary, also known as the Weekly Advertiser, started publication in August 1758, also as a vehicle for war reporting.

Because enlistments were an annual affair and many men enlisted more than once, historians calculate that the 22,858 Connecticut wartime enlistments represented about 16,000 men—or approximately 12 percent of the total population of the colony. Many of those who volunteered did so for economic reasons. The signing bonus and monthly salary provided the poor farmer and artisan, those without land or profession, with a source of income. Still, the job came at a price: 1,445 Connecticut troops died in battle, or from disease, or of other causes during the war years.

The end of the war found the colony economically depressed and deeply in debt—and it only got worse. The British government had to find a way to pay costs associated with the war (which nearly doubled the national debt). The ministers determined that the American colonies needed to share in the expense since they greatly benefited from the war’s outcome. First came tariffs on sugar, coffee, wine, and other imported commodities. Then, in 1765, Parliament adopted the notorious Stamp Act, effectively taxing all paper materials. The colonies exploded into opposition.

David Drury, a retired editor of the Hartford Courant and lifelong student of history, regularly contributes articles about Connecticut history to the Courant and other publications.