By Jason R. Mancini for Connecticut Explored

Author’s Note: The use of the term “Indian” is problematic but must be contextualized. Tribal specific labels are preferred, though often “Native” and “Indigenous” are used now in place of “Indian” as generalized descriptors. In the US, the term “Indian” has legal and political significance to tribes and how they manage their relationship with state and federal governments. “Indian” is codified in the U.S. Constitution and in subsequent “Federal Indian Law” and the “Bureau of Indian Affairs.” Historically, “Indian” people were excluded from the federal census (1790-1860) or relabeled using other race categories like “mulatto” or “colored” that resulted in their erasure from colonial, state, and federal records, a process that Native people describe as “pencil genocide.” Some tribal communities today self-identify using the term “Indian” including the Narragansett Indian Tribe, Schaghticoke Indian Tribe, and Shinnecock Indian Nation. Keeping this in mind, to better connect readers to the historical documents that serve as the foundation of this article, the term “Indian” is used to describe the Indigenous peoples of New England (and their descendants) when specific tribal labels are not applicable.

On July 17, 1710, Peter Wayamayhue, a Pequot Indian who had served as an apprentice to Lieutenant John Faning of Groton, indentured himself with the permission of his mother and her husband to Major John Merrett and Mrs. Mercy Raymond of Fishers Island, New York, for a period of two years. Though few other details are known, the terms of the agreement did stipulate that Peter would be permitted two weeks out of the year to visit his mother and other relations on the mainland.

Indentured Service and Indian Resistance

On his return to Fishers Island early in his second year of service, however, he encountered a man-of-war sloop entering Long Island Sound under the command of Lieutenant Daniel Allyn, likely of the British Royal Navy (the origin of the vessel is not noted in the court records). The crew of the vessel beckoned Wayamayhue to come onboard, which he did. One of the men then “turned his canoo adrift,” and they continued on their voyage, impressing him into service and effectively terminating his indenture—or trading one form of indenture for another, according to court records. Trickery was often used to lure men of any race into maritime work, as it was difficult, low-paying labor.

Detail from the map Connecticut, from actual survey, Hartford, CT: Hudson & Goodwin, 1811 – University of Connecticut Libraries’, Map and Geographic Information Center (MAGIC)

Two and a half years later, on January 1, 1713, while in Boston, one Peter Faning, “an Indian man late of New London,” in the company of several seamen, became very drunk on “Slip and punch” and indentured himself as a mariner’s apprentice to Lieutenant Daniel Allyn for a period of three years. Shortly thereafter, according to New London County court records, “in May 1713 he did Run away and absent himself from his [second] master…& his service.” His whereabouts were unknown until nearly three years later, when he appeared in Groton on March 27, 1716. At this time the sheriff of New London was instructed to seize Peter’s property or arrest him so that he could be arraigned before the county court. Peter then provided a sworn statement before a local justice of the peace explaining the events that had brought about his current situation.

Peter Wayamayhue and Peter Faning were, of course, the same person. Now entangled in two lawsuits resulting from his having abandoned his first indenture on Fishers Island and his second indenture with Lieutenant Allyn, Peter could easily be cast as a victim of a harsh, indifferent, and discriminatory labor market and colonial legal system that was constructed by and for the English. But Peter had picked up a few tricks of the trade to help him beat the system: an alias, an apparent willingness to violate his contractual obligations, and a seaman’s knowledge and mobility.

The experience of Peter Wayamayhue, alias Peter Faning, provides insight into the ways Indians and other people of color were adapting to and resisting a power structure that attempted to place them near the margins of Anglo-American society.

This article examines important ways that Indian people forged their existence and community structure on land, in port, and at sea. In an era of dispossession (when Indians lost their lands) and diminishing autonomy on the land, Indian mariners, as a class of transient laborers, rapidly learned to use Anglo-American structures and institutions to establish for themselves a degree of power and personal freedom. And by the end of the 18th century, as the number of Indian mariners increased, they had created maritime-based social networks that included other men of color.

Indian Mariners Navigate Colonial Legal and Economic Systems

The Treaty of Utrecht, which ended Queen Anne’s War in 1713 and terminated inter-colonial conflicts between the French and English, also transformed the power structure between the English and Indians in New England. By the mid-18th century, every Indian community in Connecticut experienced significant loss to their remaining reservation lands or a challenge to their land rights that directly resulted in dispossession. This affected the Pequot communities at Mashantucket (present-day Ledyard) and Lantern Hill (present-day North Stonington), the Mohegan in present-day Montville, Niantic in present-day East Lyme, Wangunk in Middletown, Tunxis in Farmington, Paugussett in Derby, and Schaghticoke in Kent. The loss of this land caused many Indians to leave their reservations and find new ways to live and survive in colonial society. Importantly, the dispersion of the Indian population may have contributed to the perception that Indians were vanishing. Census records, however, indicate that the Indian population, albeit small compared to the English and African populations, was clearly increasing.

As the century progressed and their depth of experience with English ways increased, Indians developed a clearer understanding of English legal and economic systems. With this, they began to regain some control over their lives and livelihoods (which at this time was largely limited to voluntary or involuntary servitude, military service of some type, or peddling crafts). Indians throughout the region were engaged in numerous court cases involving land loss and encroachment, and trials for theft, murder, and breach of service (runaways). In the first quarter of the 18th century, they also participated in the colonial legal system by appearing occasionally as jurors of inquest. Consequently, Indians became better equipped on their own or with the assistance of white overseers/legal counselors to take matters into their own hands and this extended to situations in what, ironically, was one of the more appealing work options, given the low-paying and menial work that it was, going to sea.

Twenty years after Peter Wayamayhue was defending his actions in court, George Jobe, an Indian mariner from New London, was exercising his rights as a plaintiff. Demonstrating his experience with English law, in 1733 Jobe sued the master of the Brigantine London, Naboth Graves, after he refused to pay the agreed-upon wage of 55 shillings per month. As a foremast man on a 12-month, 14-day voyage, Jobe was part of a crew that sailed to “Ireland, Madeira, Cape deVerd Island, Soranam Boston and New London” between July 11, 1732 and July 25, 1733. A writ attaching “the goods or Estate” of Graves suggests that his complaint was not quickly brushed aside. The case was later adjudicated in favor of Jobe and settled when Graves’s father-in-law “John Prentice gave special bail £68 for abiding judg.mt,” according to New London County court records.

Work at Sea an Attractive Option amid Limited Opportunities

Maritime work was not only more lucrative than other labor options for Indians, it was a good way to avoid certain types of servitude. One such case involved an Indian boy of Lyme named Tantipinant, alias Philip. In 1732, Tantipinant was bound to the service of John Lay 2nd, also of Lyme, for a term of six years and one month. At some point in December 1734, Lay and Tantipinant were on board Capt. John Sears’s sloop Elisabeth, and Lay, court records suggest, “Considering yt his Indian had so Great a Desire to Go to Sea he Thought it would be more for his Profitt to Let him go Than to keep him att home.” From that point, Tantipinant continued on as one of Sears’s hands to the West Indies islands of Antigua and Saint Christopher.

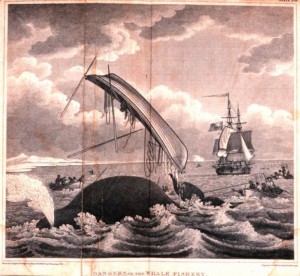

Dangers of the Whale FisheryAn account of the Arctic regions with a history and description of the northern whale-fishery by W. Scoresby, 1820 – NOAA Photo Library

During his service to Sears, when their sloop was “providentially frozen in att Rocky Hill [along the Connecticut River],” Tantipinant was released with two other sailors “to go home until ye vessel was thawed out and he [Sears] would take them on board att Saybrook.” It is not clear from the court records reporting the release if he went home to the Indian community in Lyme or if he returned to the service of John Lay. It might appear from the legal proceedings that Tantipinant did not return to Lay’s service, which was likely the source of the dispute between Lay and Sears. Tantipinant had selfish motivations to go to sea, and he must have recognized that placing himself in a situation between “masters” gave him a certain amount of power. He also knew that the power of his two masters was situational and could not extend to both land and sea.

As commerce increased around the Atlantic world, more vessels required more men. Men of color frequently ran away or deserted service on the land to pursue opportunities in maritime occupations. Runaway or deserter advertisements in local newspapers increased in the middle through late 18th century and often contained warnings to “masters of vessels” not to “harbor” or “carry away” these men.

Sailors often adopted aliases that helped conceal their identity; many were willing to desert unwelcome or unwanted situations at sea as well as on land, and this contributed to the mobility and “disappearance” of Indians. David Pompey, for example, “a light complexioned Indian…was bro’t up to the sea,” noted the New London Summary newspaper. At 22 years old, he had an alias (Thomas Ginnings), and on March 5, 1760 he had deserted from the Schooner Three Sisters. The captain, Simon Rodes, knowing that Pompey would head to sea on another ship, used particularly harsh language in a newspaper advertisement warning his fellow “masters of vessels …against harbouring, concealing or carrying off said indian on the utmost penalty of the Law.” Tracking down runaways and deserters may have been next to impossible as it had “become very fashionable for Sailors to assume some fictitious name by which they ship and are known before they sail,” as Elmo Holman notes in The American Whaleman (Longmans, Green & Co, 1928). That Pompey easily disappeared at sea suggests that there may have been many other Indians serving as sailors and thus he was easily able to go unidentified.

Communities of Color

Thus far, these accounts reflect a few individual experiences but don’t provide a sense of whether Indian sailors were a sizeable group or community nor whether they were able to form durable social networks or communities of color at sea. Fortunately, other sources are beginning to reveal a fuller picture. According to war enlistment records, by the American Revolution opportunities for men to aggregate in military-oriented companies began to emerge both on land and at sea. Among the earliest documented instances of community-level presence and involvement of Indians in New London’s maritime industry appeared during the construction of the Continental Frigate Confederacy along the Thames River in Preston. A number of the workers were associated with the Mohegan community directly across the river. Many of these men, including Peter Neshoe, Thomas Mosset, Turtle Hunter, Gurden Wyaugs, Ebenezer Tanner, Daniel Uncas, Dennis Mohegan, Simeon Ashbow, and James Jeffrey, were almost exclusively employed as ships riggers between October 1778 and February 1779. The nature of this work, which involved detailed knowledge of ship engineering and operation, suggests that these men were all by this time experienced mariners and recognized as such.

Furthermore, men from various Indian communities, including some of those involved in the construction of the Confederacy, later sailed as crew members: Simeon Ashbow and Daniel Uncas as marines, Ebenezer Tanner as a cook’s mate, and William Fagins, Jonas Peege, and Turtle Hunter as seamen. Other vessels such as the Continental Frigate Trumbull, Connecticut Frigate Oliver Cromwell, Connecticut Galley Shark, and Connecticut Brigantines Defence and Marshall had groups of Indian mariners such as Gurden Wyaugs, John Wampy, Abimelech Uncas, John Jeffords (alias Jacob Sowwas), Benjamin Cinamon, and Indian Peter serving in various capacities. The growing presence of Indians working in the maritime industry and their demonstrated ability to perform well in difficult circumstances impressed their white captains and officers. Thus, with their reputation for hard work in a merit-based industry Indians and other men of color became an important part of New London’s maritime labor force in the late 18th century.

New London also became a place where Indians could revive and adapt their social networks. The port of New London was located within 22 miles (as the crow flies) of six Indian reservations: four in Connecticut (Mohegan, Western Niantic, Mashantucket Pequot, and Lantern Hill Pequot); the Narragansett reservation in Rhode Island; and the Montauk reservation in New York. Arguably, this consortium represents and anchors one of the densest concentrations of Indian people in the Northeast. Living not just on reservations but throughout the surrounding towns of southern New England and eastern Long Island, many Indian men gravitated toward New London’s waterfront and developing urban economy.

The extent to which Indians were drawn to New London’s maritime industry was never directly mentioned in historical records, but it was, in part, reflected by the absence of Indians living on reservations. Commenting on the state of Pequot Indians at Mashantucket in May 1804, Colonel Edward Mott of Preston noted in a letter to William Hillhouse, a member of the Connecticut General Assembly, that “a Considerable Number of Aged & a Number of Females & some Males (sic) Invalids” remained on the Indian reservation and “a great part of their able & Smart Men are gone…”

Ample Evidence Discredits the Myth of “Vanishing” Indian

With the drastic reduction of Indian lands in Connecticut in the mid-18th century, so many Indians had dispersed that the English began to misunderstand and misrepresent both reservation life and the social networks that were developing to keep Indian people connected to each other. Recent work with the Records of the Collector of Customs for the Collection District of New London, Connecticut 1789-1938 has begun to illuminate Indians’ off-reservation activity. Between August 1796 and the date of Mott’s letter in 1804, nearly 80 Indian men from across the region had registered for a Seamen’s Protection Certificate or appeared on a vessel crew list arriving at or departing from New London. Hundreds more would follow.

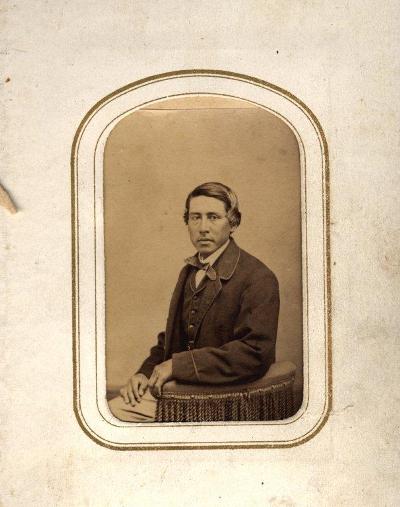

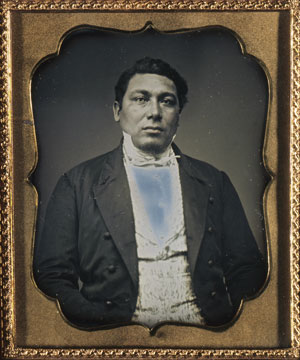

Few images of Indian seamen exist. Amos Haskins, a Wampanoag Indian, sailed on six whaling voyages from 1839 to 1861, rising through the ranks until he was appointed master of the bark Massasoit in 1851. Daguerreotype, 1850 – Courtesy of New Bedford Whaling Museum

A comparison of customs records with tribal documents and federal census records indicates that of 224 individuals specifically identified as “Indian” in the customs records between 1796 and 1860, only 28 appear on tribal lists, records, or petitions. This means that 88% of New London’s seafaring Indians never appear on tribal documents but nonetheless were born in or resided in the towns surrounding these Indian lands. Though customs records alone don’t fully reveal the way people of color identified themselves, many Indian mariners declared their tribal affiliation in other sources such as tribal petitions, census records, and legal proceedings. In the customs records, men of Indian descent were often placed in categories associated with African ancestry such as “black” or “Negro” and in categories typically associated with European ancestry such as “fair” and “light.” Further complicating this picture is the inconsistency with which many individuals were perceived and labeled. Between 1810 and 1818, Henry Fagins of Bozrah was labeled on various crew lists as “negro,” “of color,” “mulatto,” and “dark.” Similarly, in the period between 1819 and 1834, David Rogers of New London was listed as “Indian,” “colored,” “dark,” “mulatto,” and “yellow.”

Though Indian voices were strangely silent during this time, their actions were not. Beginning in 1796, with the initiation of the New London Customs Records, family and community connections can be observed and documented in the maritime industry. While the registration lists were maintained in alphabetical order over a period of decades, each mariner (often with an alphabetically different surname) received a numbered protection certificate on a certain date. When the protection certificates are reorganized sequentially and by date, a startling pattern emerges where it has become clear that many of these “vanished” men were appearing and enlisting together in New London.

This cohesion can be seen in the crews of merchant vessels reported in the New London customs records between 1796 and 1822 and principally on whaling vessels after 1821. As with other seamen, men of color appeared on these vessels in groups of three to six men. On board, they filled a variety of roles such as able seaman, ordinary seaman, cook, steward, boy, and occasionally cooper or mate. But as these fraternities were forming, they were also being obscured by the arbitrary classification of race or “complexion” by white customs officials.

At a time when the Indian population was perceived by Anglo-Americans to be vanishing, these individuals and groups were adapting and redefining themselves in ways not recognized or documented in contemporary historical accounts. The nature and extent of these connections are only realized by considering Indian reservation populations as part of a larger regional network of Indians and people of color. Assessment of the Indian presence in Connecticut has been hindered by our inability to recognize individuals as “Indians.” By considering various biases, including those of race, identity, and mobility, and by framing Indians in a population- and community-level study, we allow their rich and detailed histories to emerge.

Jason R. Mancini, PhD, is executive director of Connecticut Humanities and a former executive director of the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center. “New London’s Indian Mariners” is excerpted from his article “Beyond Reservation: Indians, Maritime Labor, and Communities of Color from Eastern Long Island Sound, 1713-1861″ in Gender, Race, Ethnicity, and Power in Maritime America (Glenn S. Gordinier, editor; Mystic, CT: Mystic Seaport, 2008).

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 7/ No. 2, SPRING 2009.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.