By Richard DeLuca

Ferries have existed in Connecticut from the earliest days of the colony because of its many rivers and streams too wide to cross by any other means. Ferries were also utilized at crossings where bridges, though feasible, were too costly or difficult to construct. Two of the earliest ferries in Connecticut operated across the Connecticut River, one at Windsor and the other at East (Quinnipiac) River in New Haven. Both ferries began operation in the 1640s. As settlement expanded, additional ferries appeared, and by 1700 Connecticut had 11 well-used ferry crossings. These were located on the Connecticut River at Windsor, Hartford, Wethersfield, Haddam, and Old Saybrook; the Saugatuck in Fairfield; the Housatonic in Stratford; the Quinnipiac in New Haven; the Niantic in East Lyme; and the Thames River at Norwich and New London.

Early Crossing Technologies and Hazards

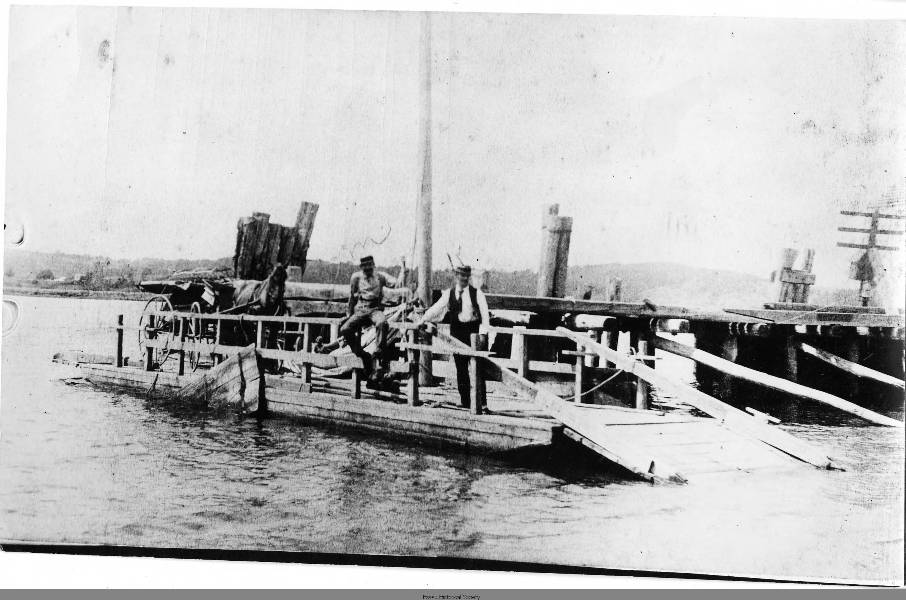

Bissell’s ferry, Windsor

The technology utilized by early Connecticut ferries varied from crossing to crossing. Most were scow-type, flat-bottomed boats that operators poled, rowed, or sailed across the water or, in the case of the Niantic ferry, pulled across using a rope line that spanned the river. A most ingenious crossing was at Windsor. Here a cable-pulley system stretched across the river and was firmly anchored to each shore. The cable passed through a pulley on the side of the ferry scow. After shoving off, the ferryman turned the boat at an angle to the river’s current, whose force moved the boat along the cable line in much the way a sailboat tacked into the wind. On the return crossing, the ferryman simply reversed the angle of the boat to the flow of the water.

Ferry crossings were not always uneventful, particularly in the colonial era. During her travels on horseback through the Connecticut colony in 1704, Sarah Kemble Knight wrote in her journal, “About seven that Evening, we come to New London Ferry; here, by reason of a very high wind, we mett with great difficulty in getting over–the Boat tos’t exceedingly, and our Horses capper’d at a very surprising Rate, and set us all in a fright.”

In the decades after Madam Knight’s vividly recorded travels, diarist Joshua Hempstead of New London wrote of using the ferry between New London and Groton frequently. Hempstead owned property in both New London and Stonington and often transported goods and livestock back and forth. In January 1755, he noted, in his usual shorthand, “Carry over the ferry 6 young Cattle in order to go to the farm to morrow.” He detailed the color and ownership of each animal and recorded that he paid the ferryman 40 shillings for the several trips necessary to get the cattle to his land in Stonington.

Unlike the building of a bridge, where the cost of construction and repair was a drain on the town treasury, a ferry was a low-cost alternative. In return for the right to collect a toll, a willing ferryman promised to provide a boat and operate the service for a given period of years, usually seven. The General Court set the fare for each ferry, with toll rates depending on the nature of the crossing. Tolls were highest at the colony’s two widest crossings, the Thames and the Connecticut Rivers, where a further surcharge was allowed for a winter crossing.

Other Transportation Developments Transform Ferry Operations

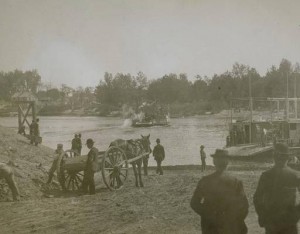

Ferry crossing at Hartford, 1895 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

As commerce and travel increased in the 18th century, additional ferry crossings appeared throughout the colony. By 1750, the number of ferries in Connecticut had grown from 11 to 26 and would peak at 30 by the end of the century. Busier crossings now utilized two boats, one stationed on either shore, and offered scheduled service as opposed to service on demand. In 1764, the colony established its first ferry across Long Island Sound, from Norwalk to the town of Huntington on Long Island.

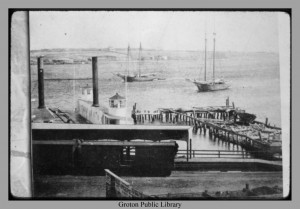

Railroad ferry across Thames River, Groton, ca. 1889 – Groton Public Library and the Treasures of Connecticut Libraries

At the turn of the century, the operations of several heavily traveled ferries were transferred from individual to town ownership. The need to finance improvements at ferry landings and to provide the larger boats needed to accommodate the wheeled carriages and stagecoaches that began to appear on Connecticut roads prompted the transfer. Towns that operated their own ferries typically used the toll revenue to subsidize the cost of their public schools—or to pay for bridge repairs.

With the construction of turnpikes in the early 1800s, bridge building became more professional and more commonplace. As joint-stock corporations were chartered to construct toll bridges around the state, the number of ferries in Connecticut fell from a high of 30 at the turn of the century to 20 by 1821, after which the number remained about the same for some 50 years. With the advent of the steamboat, many of these remaining ferries were converted to steam power.

Connecticut’s rail network also included two important ferries along the shoreline route from New Haven to Boston: one to cross the Connecticut River from Old Saybrook to Lyme; another to cross the Thames River from Groton to New London. The two crossings were made by steam-powered ferries specifically built to accommodate rail cars. Once the rail cars were loaded onto the ferry, the train’s steam locomotive stayed behind, while another engine waited to remove the cars from the ferry on the opposite shore. A rail ferry crossing excited some passengers, including Charles Dickens, who described his experience riding the Shore Line Railroad in 1868:

Two rivers had to be crossed, and each time the whole train is banged aboard a steamer. The steamer rises and falls with the river which the railroad don’t do, and the train is banged uphill or banged downhill. In coming off the steamer at one of these crossings yesterday, we were banged up to such a height that the rope broke and the carriage rushed back with a run downhill into the boat again. I whisked out in a moment, and two or three others after me, but nobody else seemed to care about it.

Such excitement ended with the construction of railroad bridges across the Connecticut and Thames rivers in 1870 and 1889, respectively.

The appearance of the automobile in the 20th century and the public funding of highway and bridge construction led to the demise of many of the state’s remaining highway ferries. By 1919, the two longest ferry crossings in the state, across the Connecticut River at Saybrook and the Thames River at New London, had been converted to bridge crossings.

A handful of ferry services still operate in Connecticut today. Two ferries operate seasonally across the Connecticut River, one on Route 160 between Rocky Hill and Glastonbury—the nation’s oldest ferry service in continuous operation, having been founded in 1655—and the other on Route 148 between Chester and Hadlyme. These two river ferries are descendants of ferry services begun at these locations in the colonial period and are operated today by the State Department of Transportation. Private operators also provide commercial ferry service for passengers and vehicles across Long Island Sound at Bridgeport and New London.

Richard DeLuca is the author of Post Roads & Iron Horses: Transportation in Connecticut from Colonial Times to the Age of Steam, published by Wesleyan University Press in 2011.