By Alex Gerrish

Dr. Alice Hamilton was a leading authority on industrial diseases and the first female faculty member at Harvard. After attending Miss Porter’s School as a young adult, Hamilton worked at Chicago’s Hull House for 22 years where she researched diseases such as typhoid and lead poisoning. Hamilton held spots on both national and international health committees, and she cemented a legacy in improving worker safety until retiring to Hadlyme, Connecticut, where she died in 1970.

A Love for Academia

Alice Hamilton was born on February 27, 1869, in New York City and grew up in Fort Wayne, Indiana. For her early education, Hamilton’s parents homeschooled Alice (and her four siblings) so she could focus on subjects they deemed important: languages, literature, and history.

Following a family tradition, Hamilton attended Miss Porter’s School in Farmington, Connecticut, with other affluent young women, such as Theodate Pope (Riddle). Hamilton recalled that “the teaching we received was the world’s worst” due to the school’s “elective curriculum.” Allowed to focus on subjects that came easily to her, Hamilton was able to ignore her weak subjects such as math and science and eventually looked back fondly on her time at the school thanks to the relationships she built there and the school’s respectful, no-nonsense atmosphere.

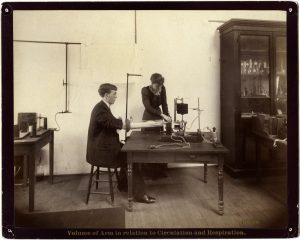

When Hamilton returned to Indiana, she remained a student, opting to study science and medicine because she “was deeply ignorant of science” and desired to know more. After studying basic science for a year in Fort Wayne, Hamilton convinced her father to let her study medicine at The Medical School of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor where she earned her doctor of medicine degree in 1893.

Hamilton gained experience interning at various hospitals around the world; she studied at Johns Hopkins and abroad in Germany at the Universities of Leipzig and Munich. These ventures helped her land a job teaching pathology in the Women’s Medical School of Northwestern University in Chicago and to realize her dream—living at Hull House.

Influences of Hull House

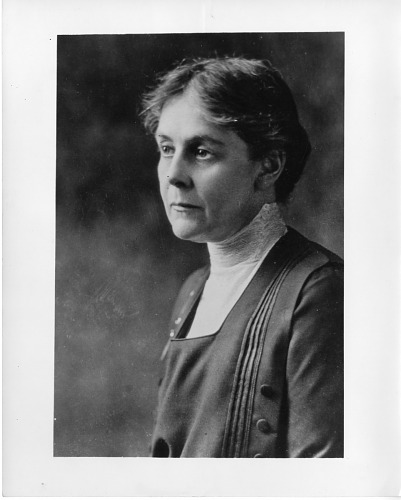

Alice Hamilton at the University of Michigan Medical School, ca. 1893 – University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library

As one of America’s most famous settlement houses, Hull House—established in 1889 by activist and reformer Jane Addams—offered education, culture, and a sense of community to lower-class Chicago residents. In addition to her teaching job at Northwestern University, Hamilton worked closely with Addams and admired her intellectual integrity and pragmaticism. In fact, as an advocate for the peace movement, Hamilton accompanied Addams to both the 1915 and 1919 International Congress of Women meetings. In addition to her involvement in social reforms, Hamilton’s work at Hull House further cultivated her interest in scientific studies and exposed her to issues faced by poorer communities.

A typhoid epidemic in the fall of 1902 began Hamilton’s interest in health disparities. Hamilton took to the streets of Chicago to investigate why typhoid affected poorer communities disproportionately. Among other observations, she noticed swarms of flies surrounding outdoor bathrooms, which she initially deemed as the main cause of typhoid during a well-publicized presentation to the Chicago Medical Society.

With further research, however, Hamilton disproved her initial theory. The real cause of the epidemic was a broken pipe in a Chicago pumping station, which allowed sewage to escape into water pipes, infecting community water. The Chicago Board of Health, however, failed to advertise this discovery. A discouraged Hamilton later stated that her fly theory “haunted me and mortified me” as it caught more public attention at the time than her other research. Hamilton’s time living and working at Hull House exposed her to many of the issues of the working class and poor communities that she researched and advocated for throughout the remainder of her career.

Becoming the Leader on Industrial Disease

Hamilton’s work at Hull House spanned 22 years and encompassed many of her biggest accomplishments. In 1910, she began work at the Illinois Commission on Occupational Diseases as a medical investigator, which tasked her with researching industrial sickness and mortality rates in the area. Hamilton focused on lead poisoning in industries such as enamelware, painting, and rubber making. At the time, few studied the negative effects of lead or recommended precautions when working with it.

Hamilton visited factories, observed hospital records, and made home visits to workers. She concluded that many of the workers’ illnesses and deaths stemmed from their occupations, finding that over 70 industrial processes—including paint production and enameling—exposed workers to lead poisoning. In 1913, Hamilton joined the newly founded US Department of Labor, which allowed her research to extend nationally. The department only paid her if her reports were accepted, but Hamilton’s research resulted in many state and federal laws ensuring workers’ safety. Hamilton also assisted factory workers by sharing solutions with them directly.

Hamilton became the nation’s leading authority on lead poisoning and industrial diseases and to address this growing field, Harvard University created a school of industrial medicine and made Hamilton the first female faculty member of Harvard—an all-male school at the time. Despite her faculty position, Harvard excluded Hamilton from attending the Faculty Club, marching in commencement, or obtaining football tickets.

Rather than secluding herself on campus, Hamilton remained active in her field during this time. From 1924 to 1930, she was a member of the League of Nations Health Commission and was invited to go to Russia in 1924 to survey their work in industrial medicine. Hamilton conducted research well into the 1930s on harmful chemicals at the request of presidents and health professionals and wrote two influential books while at Harvard: Industrial Poisons in the United States and Industrial Toxins. Hamilton retired at 65 years old—Harvard’s mandatory retirement age.

Retirement in Hadlyme

Hamilton lived the remainder of her life in Hadlyme, Connecticut, along the Connecticut River, where she took up residence 15 years earlier. Sharing the Hadlyme house with various family members, she was also neighbors and friends with Yukitaka Osaki—actor William Gillette’s valet and assistant. Hamilton remained a social, political, and academic activist. In 1943, she documented her life’s work in an autobiography, Exploring the Dangerous Trades.

Hamilton died on September 22, 1970, at 101 years old. She is buried in Cove Cemetery in Hadlyme. Her legacy as a leading authority on industrial disease lives on through the countless laws and regulations she inspired to help keep workers safe.

Alex Gerrish is the Programs Manager at the Noah Webster House and holds a B.A. in American Studies from Western New England University.