Written by William Devlin for the Connecticut History Review

Pollution of Connecticut’s waters by industrial waste and sewage in the decades after the Civil War was arguably the state’s first modern environmental crisis. In the end it was the actions of ordinary citizens, operating through the courts, that began a long journey toward waterway restoration by laying its legal foundations.

In 1886, New Haven health officer S. W. Williston reported to the General Assembly that “nearly every stream adapted to manufacturing requirements in the state is contaminated” with dyes, acids, chemicals, and other manufacturing waste from the state’s burgeoning industries.

Connecticut’s Sewage Problem

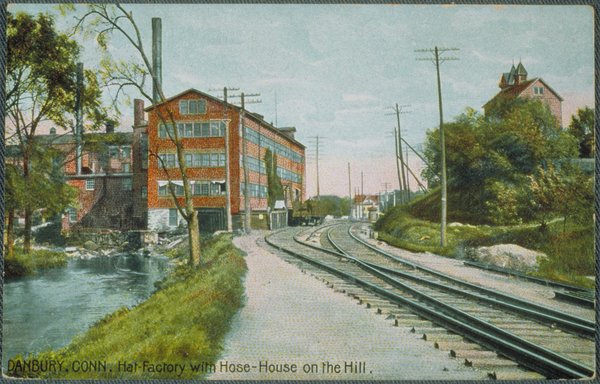

Workmen extend Danbury’s sewer line to the site of its new treatment plant in the wake of the decision in Morgan v. Danbury, c.1896. – Danbury Museum and Historical Society.

Then there was sewage. Rapidly growing cities and towns began fearing polluted wells and stagnant water that caused diseases such as typhoid fever. That disease alone sickened thousands and killed 400-500 state residents of working age every year. For cities on Long Island Sound and on tidal rivers, “the solution to pollution was dilution,” but most of the state’s inland manufacturing centers were located on streams that were shallow, sluggish, or had low seasonal flows.

The science of treating sewage was in its infancy, and treatment added costs to an already expensive project. Local economic factors usually dictated dumping into the nearest watercourse. “The rule now is to let the law of gravity prevail over the laws of health,” quipped the Hartford Courant in 1886.

The results were predictable. Mill owners found it difficult to hire workers as their millponds filled up with sewage. Farm fields were fouled when rivers flooded, and cattle developed rashes after wading into polluted streams. Odors carried far downstream, crossing town boundaries.

State agencies such as the State Board of Health (established in 1878) and the Board of Fish and Game, along with progressive farmers such as James Bradford Olcott, sounded alarms. Their pleas fell on deaf ears in a General Assembly dominated by rural interests. The Assembly had routinely granted cities the right in their city charters to release sewage into rivers. “The cities have drained the population from the towns; now they would drain their filth and make the towns pay for it. The cities are rich enough to find ways and means,” sneered Representative Milon Pratt of Old Saybrook in a debate in 1897, voicing a common attitude.

Early Environmental Lawsuits

Superior Court Judge George Wakeman Wheeler’s decision in Morgan v. Danbury was the strongest of its time in the state. He later served for 20 years on the State Supreme Court, including 10 as Chief Justice, and was considered by President Woodrow Wilson for the U.S. Supreme Court – Bridgeport History Center, Bridgeport Public Library.

While industry proved so important to the state’s economy that its waste remained an untouchable subject, sewage pollution generated wide controversy. Meriden, Wallingford, Bristol, Waterbury, Brookfield, and Torrington, along with scores of other towns and individuals, all became defendants or plaintiffs in lawsuits or other disputes.

The city of New Britain’s sewer system, for example, emptied into sluggish Piper’s Brook. When the State Supreme Court upheld a successful lawsuit brought by Henry Kellogg of Newington over the brook’s pollution in 1891, a wave of lawsuits began against cities across the state. Over a decade, New Britain alone had to pay settlements to 27 downstream residents (mostly in Newington), found itself sued by Hartford and Middletown, and finally had to build a treatment plant at a site in a neighboring town.

In their defense, cities claimed that the streams were already polluted and that the General Assembly had granted them the right to discharge sewage into their rivers. Judge George Wakeman Wheeler demolished those defenses in Morgan v. Danbury, a case involving Danbury’s Still River. There, an “alliance” of over 40 downstream mill owners and farmers from the rural Beaver Brook district of Danbury and the neighboring town of Brookfield joined the suit of mill owner George Morgan against Danbury, asking for damages and an injunction. A two-month long, “David versus Goliath” battle ensued. Wheeler came down strongly on the farmers’ side. The common law doctrine of riparian rights held that downstream users of a stream had a right to its use unimpeded by the actions of upstream users. Wheeler asserted that Danbury had no right to create a “nuisance,” even if for a public use. He ordered Danbury to build a treatment plant within two years, and the city complied.

Tightening Regulations

In the wake of the Danbury decision, Governor Lorrin A. Cook pushed a reluctant General Assembly to create a Sewage Commission in 1897 to advise cities about sewage treatment. By 1901, sixteen cities and boroughs were treating their sewage or had plans in the works. The state’s courts continued to issue decisions that upheld the rights of downstream property owners over polluting cities and boroughs. As a result, a 1903 U.S. Geological Survey publication crowed that “Connecticut’s courts have taken no uncertain stand…in no other state of the union has there been (such) unequivocal judicial disapproval of the practice of destroying water resources.”

But absent any enforcement or government aid for pollution control, cities found ways to circumvent the mandates. In Waterbury, the Platt Brothers, manufacturers of brass eyelets with a plant on the Naugatuck River, fought a decade-long battle with the city government that resulted in no fewer than three state supreme court decisions. The courts eventually ordered Waterbury to refrain from discharging raw sewage into the Naugatuck during six months of low flow in the summer and autumn.

Waterbury subsequently built a massive outfall sewer completed in 1907 but escaped building a sewage treatment plant until 1951. Other cities followed suit, particularly in the Naugatuck Valley.

A sea of change occurred during the Progressive Era. The press and public opinion, dismayed by the compromise of recreational opportunities and the decline of the Long Island Sound oystering industry due to ongoing pollution, began to talk about clean water as a natural right. A wide range of organizations mobilized behind bills that would have given the State Board of Health full jurisdiction over discharges into the state’s waters, but a reluctant legislature instead created an Industrial Waste Board in 1918 and a Water Board with power over discharges into streams (a forerunner of today’s DEEP) in 1925.

Its carrot-and-stick approach, using state and federal aid and the power to issue permits and fines, bore fruit over time. By 1963, 90% of the state’s municipal sewage and 40% of its industrial waste was being treated. A final push in the mid-60s under Governor John Dempsey brought about a Clean Water Act in 1967 that became a model for the Federal Clean Water Act five years later.

William Devlin was a history teacher, an adjunct instructor of geography at Western Connecticut State University and is the author of books and articles about Danbury-area history. He has been a longtime volunteer for environmental causes. This story is based on his longer paper for the Spring 2020 issue of Connecticut History Review.