By David Drury

The greatest epidemic in human history, the so-called Spanish flu of 1918, killed tens of millions of people worldwide. Some recent estimates have placed the death toll at greater than 100 million. An estimated 675,000 Americans perished, including some 9,000 men, women, and children in Connecticut—nearly 1% of the state’s population.

Origins of the Spanish Flu

Influenza was little understood in 1918 because viruses were as yet unknown to medical science. The speed with which the Spanish flu hit, the devastating array of symptoms that followed, and the fact that the victims were typically young, otherwise healthy adults, confounded and overwhelmed public health officials. A person infected could be perfectly healthy one day and dead 48 hours later, usually from pneumonia or another opportunistic bacterial infection of the lungs. Penicillin would not be discovered until 1928.

Exactly where the killer virus originated remains a subject of conjecture. Medical researchers today believe that, like later human influenza strains, it started as an avian virus, perhaps among the bird populations of the Far East. It then transitioned to humans, with pigs a likely intermediary.

The pandemic coincided with another devastating event: the Great War, more commonly known today as World War I. During the late winter and spring of 1918, virulent flu outbreaks were reported among doughboys training at Fort Riley, Kansas, in the resort town of San Sebastian, Spain, and sweeping through the trenches of the Western Front, sickening troops on both sides of the epic conflict. A mid-summer lull followed, a period in which virologists believe the virus mutated, reappearing in the US in August more deadly than before.

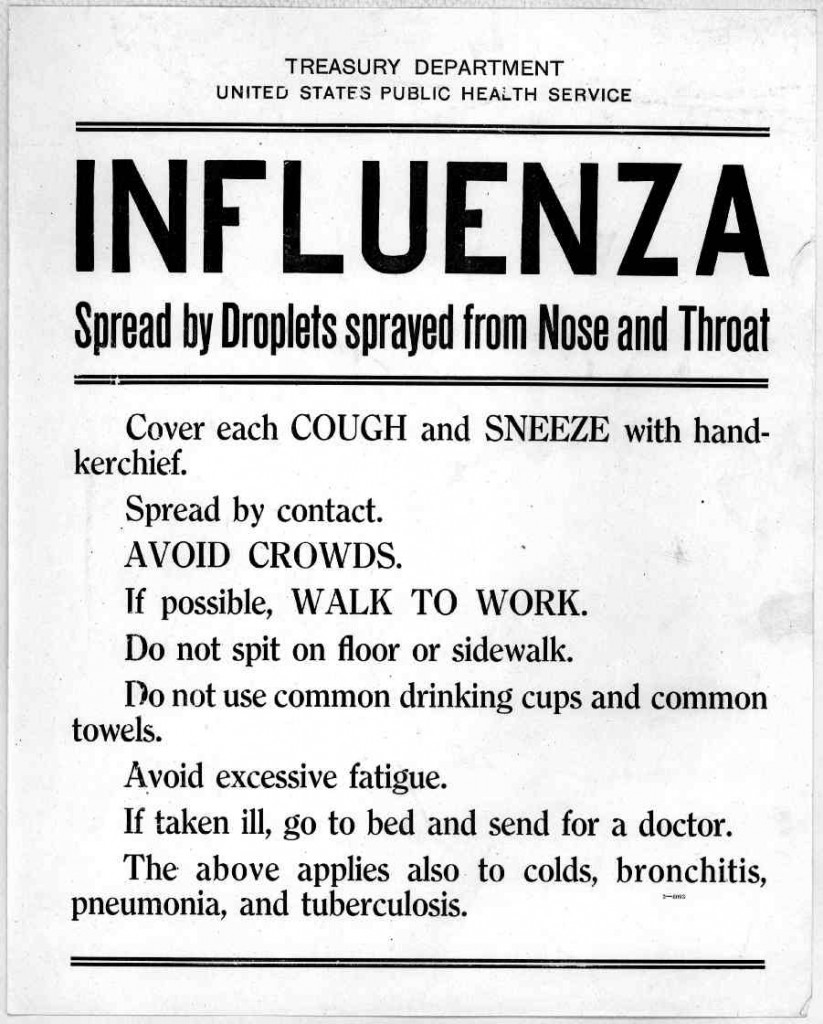

United States Public health service flyer, 1918 – Library of Congress, American Memory

Sickness Spreads to the States

The East Coast ports provided the means of entry and military bases where millions of young Americans were being massed for training prior to embarkation to Europe gave it sustenance. Camp Devens, a large US Army base outside of Boston, was a scene of profound misery. Nearly 11,000 influenza cases were reported by September 23. There were not enough doctors, nurses, or hospital beds to care for the sick. Death spared no one. The Reverend William Cornish, a Methodist minister from Windsor, Connecticut, who was called to duty as an army chaplain, was among the early victims. By late September, a shortage of caskets prevented authorities from shipping bodies of the mortally stricken back to their homes, the father of one Hartford serviceman told The Hartford Courant.

Connecticut Contracts the Flu

The port of New London saw the first outbreak in Connecticut. Between 600 and 700 influenza cases were reported in the city by the third week of September. About half of those stricken were service personnel, many of whom were lodged in private homes. “The entire city is under quarantine for men in uniforms who are not allowed to leave New London without a special physician’s permit,” The Courant reported.

From New London County, the “Spanish Lady” (as it was euphemistically known) headed north and west, spreading across the state. Five hundred cases were reported in Hartford by September 21; Willimantic schools were ordered closed a week later. On September 30, students at Yale University were provided with muslin masks to cover their noses and mouths while attending public gatherings.

By the first week of October, local officials in several communities had cancelled fairs, football games, and theater performances. October marked the outbreak’s deadliest month in Connecticut, with more than 5,000 flu-related fatalities recorded. For four successive weeks, beginning on October 12, deaths totaled in excess of 1,000 per week, reaching a peak of more than 1,700 during the week of October 19.

The State Responds

Public health officials found themselves under siege. John T. Black, the commissioner of the State Department of Health, urged doctors and nurses to remain in the state and on-call at all times. In New Britain, private homes were opened to accept overflow cases from New Britain Hospital. On October 17, Hartford Hospital began using the Hartford Golf Club as an emergency hospital for flu patients, staffing the facility with one physician and relying upon volunteers to provide nursing care. In Waterbury, 654 flu-related deaths were recorded in the month, the highest total among all Connecticut localities; in one day alone, 33 burial permits were issued in the Brass City for those who had died in the previous 24 hours.

The state’s cities and industrialized towns, their densely populated neighborhoods swollen with immigrant families, were particularly vulnerable. Whole families were wiped out, with adults and children all succumbing at home in their beds: in Meriden, it was reported that a 37-year-old man died following the deaths of his wife, his 15-year-old daughter, his 2-year-old son, and a sister-in-law, who lived with the family, all within the span of three weeks.

As the numbers of the sick and dying grew, local leaders responded by closing churches and schools, cancelling public events—even wildly popular Liberty Loan drives—and banning public funerals. No statewide bans were instituted. Instead, public service announcements in print and on the movie screens urged cold-sufferers to stay home, cover mouths and noses when coughing or sneezing, and avoid the risk of infecting others. With the medical profession seemingly at a loss in how to treat the disease or prevent its spread, many households fell back on age-old home remedies, including camphor (“placed in a bag and hung from one’s neck,” according to The Courant), onions (either eaten or worn on the body), whiskey, and prayer.

By mid-November, with the signing of the Armistice signaling the end of the Great War, the numbers of new cases and flu and pneumonia-related deaths in Connecticut dropped sharply. While the epidemic would linger into 1919, the worst had passed. By the time the epidemic had passed, estimates are that one-quarter of Connecticut’s residents had fallen ill of the influenza. “So far as the United States is concerned, it [influenza] has proved itself more deadly than the war and is likely to cause here a greater money loss than the war,” The Courant noted on November 30, 1918.

The genetic makeup and the proteins that made the Spanish Influenza virus (H1N1 strain) so deadly were identified in the late 20th century from tissue samples of its victims. By unlocking its mysteries, researchers have hoped to gain insights that will help them to better understand the ever-mutating influenza virus and engineer appropriate vaccines to head off another world pandemic.

For those who lived through the 1918 flu, life was never same. Interviewed for the film, Influenza 1918, part of The American Experience series on public television, 85-year-old John Delano of New Haven recalled what it was like for him, then age 6:

After the flu, I was a pretty lonely kid. All my friends had died. These were the friends I had played with for years, gone to school with. When I lost them, my whole world changed. People didn’t seem as friendly as before, they didn’t visit each other, bring food over, have parties all the time. The neighborhood changed. People changed. Everything changed.

David Drury, a retired editor of The Hartford Courant and lifelong student of history, regularly contributes articles about Connecticut history to The Courant and other publications.