By Emma Wiley

Described once by the Hartford Courant Magazine as “an active community leader for all people,” Mary Townsend Seymour was a leading organizer, civil rights activist, suffragist, and so much more in Hartford during the early 20th century.

Mary’s Early Life

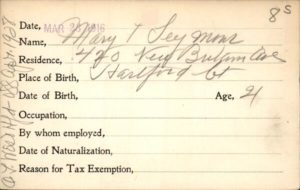

Jacob and Emma Townsend welcomed the birth of their daughter, Mary Emma Townsend, on May 10, 1873—the youngest of their seven children. Mary’s childhood is not well-documented, but at the end of her mother’s life in 1888, the Seymours—a prominent family in Hartford’s Black community—adopted 15-year-old Mary. She took it upon herself to officially change her name with Hartford’s Hall of Record to Mary Emma Townsend Seymour.

Three years later, Mary married Frederick Seymour—a postal worker and son in the Seymour family—on December 16, 1891. They had a son, Richard, in 1892, but he did not live past infancy. Mary devoted the rest of her life to fighting for the civil rights and fair treatment of her community—from voting rights for women to anti-segregation advocacy to honest wages for Black factory workers and so much more.

Founder of the Hartford N.A.A.C.P.

Mary Townsend Seymour’s Letter to the Editor printed in the Hartford Courant on July 2, 1918, concerning the use of offensive language to describe Black American soldiers – Hartford Courant

Mary Townsend Seymour is perhaps best known for her integral involvement founding the Hartford chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.)—an interracial national organization founded in 1909 to advance justice and civil rights for African Americans.

The Great Migration—the mass movement of African Americans from the American South to the North, Midwest, and West—began in the early 20th century and lasted until the 1970s. Many southern African Americans moved to find new economic and employment opportunities and get away from racial violence, disenfranchisement, and entrenched Jim Crow policies. Consistent with trends in other northern cities, Hartford’s Black population increased by 143 percent in the decade between 1910 and 1920. This shift in population put stress on racial tensions in Hartford, including prompting a discussion of segregating the city’s schools.

In response to both the racism and discrimination in Hartford and the nation, Mary Townsend Seymour opted for action. On October 9, 1917, in their home at 420 New Britain Avenue in Hartford, Mary and Frederick hosted a group of local activists and leaders in addition to three national N.A.A.C.P. leaders—W.E.B. Du Bois, Mary White Ovington, and James Weldon Johnson. That night, the group decided to form a Hartford chapter of the N.A.A.C.P.; they elected William Service Bell as the president and Mary Townsend Seymour as vice president.

Seymour took care of the administrative needs of the chapter and became the spokesperson of the organization when William Bell went overseas to serve in World War I. According to former Connecticut State Archivist Mark H. Jones, Seymour was unique because “instead of dealing primarily with Hartford’s white male leaders or through the black male Interfaith Alliance of ministers, she collaborated with a small group of influential elite white women reformers” such as Josephine Bennett. Through her role in the N.A.A.C.P. as well as participation in other organizations such as the Colored Women’s League of Hartford, Seymour advocated for fair treatment of Black laborers, pursued equal rights for Black soldiers, and raised awareness about the lynchings taking place in the country.

Seymour understood the power of language and periodically wrote to newspapers, shedding light on discrimination and injustices. For example, as hundreds of thousands of African Americans served in World War I, Seymour wrote a letter to the Hartford Courant to object to the way that articles referred to Black soldiers. Unfortunately, the editorial response printed directly beneath Seymour’s letter was dismissive and declared that “the writer is too sensitive.”

Seymour’s work during the war was not limited to the newspaper; she also joined the Red Cross and helped form a local chapter of The Circle for Negro War Relief in 1918 which helped take care of soldiers and their families.

In June 1920, The Crisis—the national magazine of the N.A.A.C.P.—published Seymour’s exposé of the working conditions for Black women in Hartford’s tobacco factories. Hearing from workers at N.A.A.C.P. meetings about how foremen cheated them out of wages, Seymour decided to gain firsthand experience and went undercover as a tobacco stripper at one of the factories. Afterwards, Seymour helped 60 women organize into a union and gain seats in the Central Labor Union (the collective organization with representatives from numerous unions). According to the exposé, Seymour read different Crisis articles monthly to the Central Labor Union meetings, eventually inspiring some of the white members to see the intersections between racial and economic oppression.

Seymour became less involved in the N.A.A.C.P. in the late 1920s. A 1952 Hartford Courant Magazine article, however, celebrating the 35th anniversary of the Hartford N.A.A.C.P., declared that Seymour was a “woman of culture whose mind and heart went out, not only to the oppressed people of her own race, but to subject people everywhere.”

Seymour as a Suffragist

In addition to her work with the N.A.A.C.P., Seymour was an active suffragist. By the early 20th century, however, the American suffrage movement had a long history of systematically and intentionally excluding Black women. Southern states were the most challenging opponents to women’s suffrage and passing the 19th Amendment—white suffragists often ostracized Black suffragists, even in the North, to appeal to white southerners.

Seymour did not accept this exclusion and persistently wrote to white suffragists and leveraged her relationships with other well-connected women. In addition, the newspapers routinely listed her as part of numerous suffragist and voting rights organizations including the Hartford Equal Franchise League and the Connecticut League of Women Voters.

In 1920, after fighting for women’s right to vote, Seymour decided to throw her own hat in the ring and ran for state representative on the Farmer-Labor ballot. Even though she lost the election, she was the first African American woman to run for the Connecticut General Assembly. Seymour ran and lost again in 1922, this time for Connecticut secretary of state. Newspapers as far away as Wichita, Kansas and Guthrie, Oklahoma noted the impact of her campaign.

Mary Townsend Seymour’s Legacy

On January 12, 1957, after a long activist career, Mary Townsend Seymour died at the age of 83. Despite Seymour’s activism and her profound impact on civil rights, her involvement was rarely appreciated or celebrated outside of the Hartford community for much of the late 20th century. Even during her life, many official records did not capture the full extent of her influence. For example, the US Censuses never listed a profession for Mary and there is only one known image of her—a grainy photograph from the Hartford Courant.

In 2006, however, Seymour was posthumously inducted into the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame after three eighth grade girls from Bloomfield, Connecticut nominated her for the honor. In the Hall’s tribute film, Seymour’s grandnephew, Alan Green, described his aunt as “tall, strong, with a commanding presence.” Today, the Connecticut Freedom Trail includes her gravesite in Hartford’s Old North Cemetery on its list of sites.

Emma Wiley is the Digital Humanities Content Manager at CT Humanities and holds a B.A. in History from Vassar College.