by Victoria Smith Ellison

From 1910 to 1930, a significant shift in the demographics of northern US cities took place. This period, known as the Great Migration, saw a mass movement as African Americans left the South in search of job opportunities and a renewed life. Charles S. Johnson, a prominent African American sociologist whose own family had journeyed from Virginia to Illinois when he was a boy, published several reports on the African American populations in different cities. In Johnson’s 1921 report, “The Negro Population of Hartford, Connecticut,” readers see through his eyes why African Americans migrated to Hartford, the challenges they faced, and how they made the communities they lived in their own. Johnson issued the report while serving as the director of the Department of Research and Investigations for the National Urban League, an organization founded in 1911 to address the resettlement needs of African Americans migrating from rural areas to cities in the North.

A Statistical Snapshot of Segregation

Between 1910 and 1920, Hartford’s population increased significantly. According to Johnson’s report, “…within this decade the [population] increase was 140 percent, one of the largest percentage increases of the Northern cities affected by the movement.” When African Americans initially arrived in Hartford, the job prospects, particularly in the tobacco industry, seemed promising. However, many of them discovered that the jobs were not always equally available to all. The newly arrived African Americans often competed for the same jobs as Italian and Polish immigrants, who had also settled in Hartford. Employers often favored these ethnic minorities when hiring, which made race a factor for those seeking work. The declaration of World War I brought more hope for African American migrants. There was an increase in job openings as immigration was banned—and as a number of the immigrant residents of Hartford returned to Europe fight for their homelands.

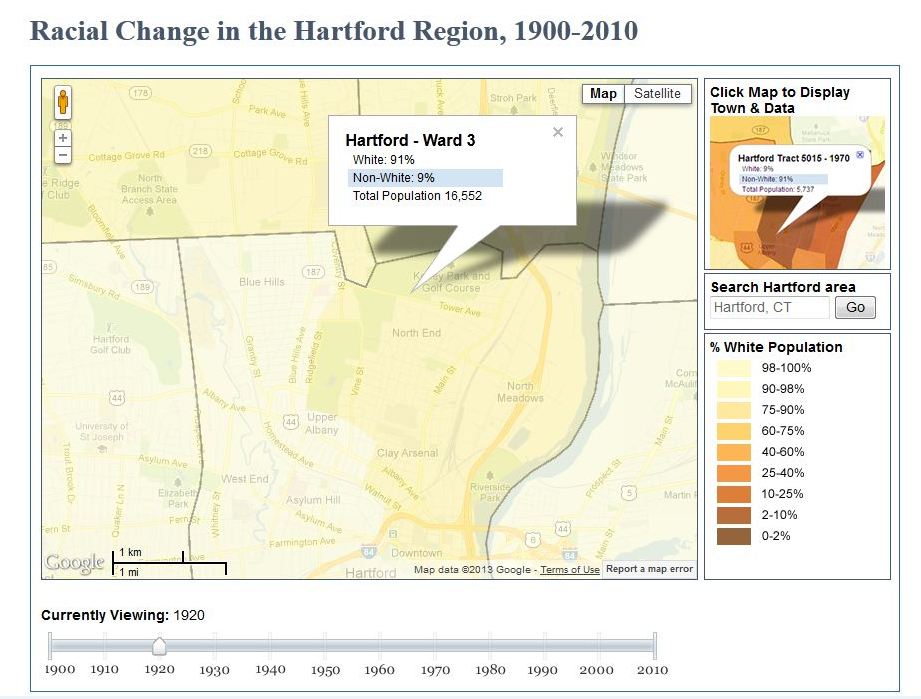

Racial Change Map 1920 displaying the African American Population concentrated in the Northeast part of Hartford, Racial Change in the Hartford Region, 1900-2010 – University of Connecticut Libraries, Map and Geographic Information Center (MAGIC)

Adjusting to urban life in Hartford was not an easy transition for migrants. The new African American arrivals faced many challenges in addition to the lack of equal access to job opportunities. They faced backlash from African Americans who had lived in the North prior to the Great Migration. Members of existing communities oftentimes tried to distinguish themselves from the newcomers and blamed them for frictions or difficulties that occurred. New arrivals also felt the manifestations of racism. They were segregated in certain areas of the city and endured harsh living conditions. According to Johnson, “The heaviest concentration of Negroes was found in Districts IV and V, the only housing actually available for the Negro newcomers.” He described these areas, which were bounded on their eastern edge by the Connecticut River, as “among the oldest and most deteriorated sections of the city … .” Those who could acquire the means to move to better housing did so, but many others remained behind.

Churches Serve as Community Focal Points

Despite these less than ideal circumstances, those who lived in the worst of the segregated areas found ways to uplift their communities. African American churches played a significant role not only as religious institutions but in their role as social centers where members could air grievances, seek aid, and make connections. But differences between the Southern newcomers and Hartford’s established African American communities existed here, too, on matters of belief, church policy, and even styles of worship.

Johnson concluded his report with words of encouragement and advice for the new and existing African Americans who called Hartford home. He stated that despite the differences that seemed to draw them apart, there were a number of individual ministers who possessed strong leadership skills. If they worked to overcome their differences and collaborated, Johnson believed that they would then be able to effectively tackle the social obstacles that oppressed their communities and denied African Americans equal opportunities for attaining a better life.

Victoria Smith Ellison, a sophomore at Trinity College in Hartford during the 2012-13 academic year, is an Educational Studies major.