By Shirley T. Wajda

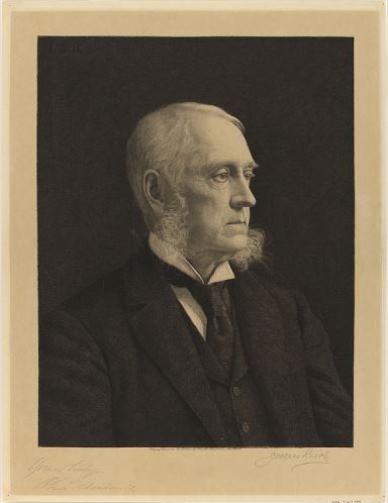

Charles McLean Andrews was one of the most distinguished historians of his time, generally recognized as the master of American colonial history. A graduate of Trinity College in Hartford (1884) and a Johns Hopkins University PhD (1889), Andrews taught at Bryn Mawr College (1889–1907) and at Johns Hopkins (1907–1910) before serving as Farnham Professor at Yale University from 1910 until his retirement in 1931. He received the Pulitzer Prize in History in 1935 and in 1937, was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and was awarded the gold medal (given only once every ten years) by the National Institute of Arts and Letters for outstanding work in history. He received honorary doctorates from Harvard, Yale, Johns Hopkins, and Lehigh universities. When he received the Harvard degree, on the occasion of Harvard’s tercentenary celebration, Andrews was cited as “a great teacher and scholar, foremost among the living historians of America.” Between 1888 and 1937, he was the author of more than one hundred books, articles, essays, and published addresses and estimated that, in addition, he had written some 360 book reviews, newspaper articles, and short notes.

When he wrote, shortly before his death, that “uppermost in his mind” was “to do something and to be somebody,” Andrews invoked the sense of mission his Puritan forefathers and his own evangelist father, William Watson Andrews (1810–1897), possessed. Having a Connecticut ancestry of seven generations and describing himself as “a Puritan of the Puritans,” Andrews not surprisingly exhibited a deep interest in American colonial history and the early history of Connecticut. His first book was The River Towns of Connecticut (1889), a study of the settlement of Wethersfield, Hartford, and Windsor. He also served as a member of the Connecticut Tercentenary Commission Committee on Historical Publications between 1933 and 1936.

Yet, Andrews did not devote himself to a glorification of early New England, as many adherents of the Colonial Revival promoted at this time. He observed, for example, that Puritan ideas “regarding the political and religious organization of society [were] far removed from the democratic ideas of later times.” Nor was Andrews a spokesman for an “uncritical Americanism” in charting the history of the American colonies. Rather, Andrews, along with Herbert L. Osgood (1855–1918) of Columbia University, forged a new approach to American colonial history: the so-called “imperial” interpretation.

A research visit to England’s Public Record Office in 1893 revealed to Andrews the necessity of a more inclusive political history of the American colonies and England. Andrews believed that previous colonial historians emphasized the colonies without sufficient attention to their imperial ties with Great Britain. In such works as The Colonial Period (1912), Andrews accordingly gave as much attention to England as to America. The interpretation of the coming of the American Revolution in Andrews was not an account of conscious British tyranny, a view characteristic of too many American historians before Andrews. According to Andrews, the Anglo-American clash was inevitable because the British statesmen of the era could not overcome the limitations of their society in order to relate to the dynamic society evolving in America. The essence of the Andrews approach to the Anglo-American worlds of the 17th and 18th centuries can best be examined in The Colonial Background of the American Revolution (1924) and in his masterpiece, the four-volume Colonial Period of American History (1934–1937).

Evangeline Walker Andrews (1869–1962)

Andrews met his wife Evangeline Holcombe Walker, then a Bryn Mawr student, in 1893. They married two years later, beginning a lifelong partnership in historical research, writing, and editing. Evangeline ran the household and raised their two children, edited Andrews’s prose, traveled with him at times, and published under her own name several works of note.

Born in London and raised in Indianapolis, Indiana, Evangeline Walker Andrews attended the Girls’ Classical School before attending Bryn Mawr. She founded the Bryn Mawr Alumnae Society and served as its president between 1892 and 1897. A specialist in Elizabethan history, Evangeline Andrews is credited with reviving May Day celebrations in the United States through her staging, in 1900, of the Elizabeth May-Day Festival at Bryn Mawr. She served in several administrative capacities, including headmistress (1921–1922) at the Ethel Walker School, founded by and named after her sister in 1911 and located first in Lakewood, New Jersey, and then Simsbury, Connecticut, in 1917.

Evangeline Walker Andrews involved herself in several of Connecticut’s historical societies and preservation efforts. She served as president of the Connecticut Society of the Colonial Dames of America from 1927 to 1933 and as chair of the restoration of the Henry Whitfield House in Guilford.

Shirley T. Wajda is the Curator of History at the Michigan State University Museum