By Jeannine Henderson-Shifflett

Sunday, March 11, began as an unseasonably warm day but, as the day turned to evening, the weather turned colder. As the snow started to fall, optimistic residents believed that the storm would not last, and many thought it was “just winter breaking up.” Even the Hartford Courant reported that the snow would soon turn to rain.

The snow continued to fall into the next day. Still confident that the storm would not last, residents around the state headed to work or school. By mid-morning, however, reports from Southington told of a black cloud appearing on the horizon and sweeping over the area. The sky filled with flakes and visibility declined drastically as temperatures plummeted to 15° degrees below zero and wind speeds increased. People began to leave work or school to return home, but some waited too long and had to wait out the storm where they were. In New Britain, for example, the principal of Smith School made sure that his students got home safely, but he was trapped at the school for 36 hours without food or supplies.

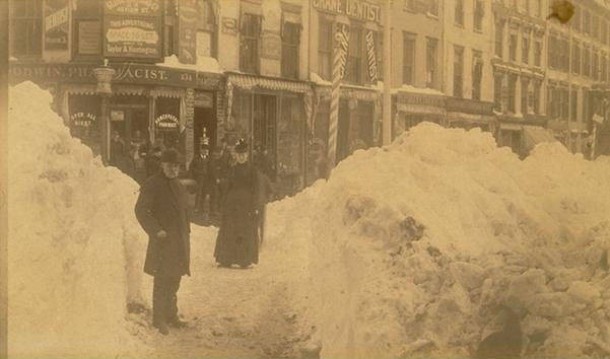

New Haven, street unknown. New Haven recorded forty foot drifts – Archives & Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries

The Great White Hurricane

On the first day of the storm, which lasted three days, over 30 inches of snow fell. Two days later, the total reached 45 inches. Today’s meteorologists now agree that two main factors contributed to the large amount of snowfall. The first was the amount of water vapor present in the air. The vapor came from the easterly and northeasterly winds that started in the Atlantic Ocean and then blanketed New England. The second factor was a sudden drop in temperature, which not only made for ideal snow conditions but also added to the already large amount of water vapor in the air.

In total, Connecticut received between 20 and 50 inches in various parts of the state, with snow drifts measuring 12 feet and higher. New Haven, for example, recorded drifts measuring 40 feet. More than 400 people across the East Coast died in the storm, and estimates placed total storm damage at $20 million. The storm, later called the “Great White Hurricane,” marooned trains, stranded deliverymen and laid up coal wagons.

In a reminiscence published in the Redding Times in 1960, Helen N. Upson, who lived through the storm on her family’s Redding farm, recalled that on a neighboring dairy farm “snow was so deep in the stables that cows and horses stood to their middles in it” and that “children, men and horses were everywhere struggling against the driving, blinding, drifting snow.”

Residents Face Storm with Humor and Heroism

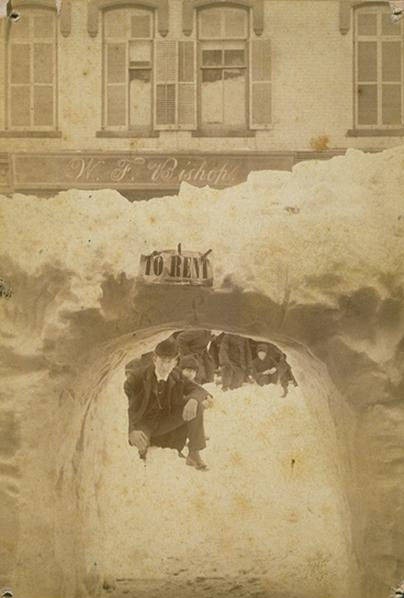

While the storm caught people by surprise, many tried to make the best of it. Humor and good nature often prevailed as the state dug its way out. People escaped snow-imposed imprisonment by crawling out of second-story windows and climbing down ladders. Some placed signs on snowbanks and snowdrifts offering them “for rent” and warning passersby to keep off the grass. When the railroad system ground to a halt, stranded travelers made the best of the situation by singing and watching performances by fellow passengers. A group of 53 stranded in Vernon even renamed the depot the “Vernon Hotel.”

Bridgeport, street unknown. Note the children in the background and the “To Rent” sign – Connecticut Historical Society

And, even in the face of the danger that the storm presented, many residents attempted to help those in need. A small girl in New Britain was on the verge of freezing to death before rescuers found her and brought her to safety. Also in New Britain, two men rescued a third who was intoxicated and trapped in a snowdrift. Visibility was so poor that a father rescued his own son without realizing his identity until they were safely inside. Similar situations occurred all over the state.

In Montville, two young brothers, Gurdon and Legrand Chapell, left their family’s home and got lost crossing the pasture to their grandparents’ house. Taking cover by a stone wall, the two little boys were covered with snow, lost consciousness and were discovered almost a day later by rescuers. They were alive, having been protected by the insulating blanket of snow. Two women workers at a Bridgeport factory were not as lucky; they tried to make it home through the storm on Monday and were found, dead in each others’ arms, two days later. In his hotel in New York City, which was also hard hit by the storm, Samuel Clemens of Hartford, better known as Mark Twain, wrote home to his spouse that he was “out of wife, out of children, out of line, and out of cigars.”

The state shut down for the duration of the storm. Businesses closed, mail carriers and milkmen stopped making deliveries, and printing presses and railroads stood still. With telephone and telegraph lines down, the storm left residents without any means of outside communication. So eager were residents for news of the storm that some young newsboys-turned-scalpers sold copies of the usually 2-penny Hartford Courant for 50 cents.

Digging Out

Snow removal immediately became a priority for the state. Some snowdrifts stood between one and two stories high; the tallest on record was in Cheshire where residents measured a snowdrift 38 feet high. The Hartford Courant urged authorities to pay whatever it cost to clear the snow, even if the amount was in the thousands. Paid workers earned $1.75 per day for their efforts, but others volunteered their time. Horses and oxen pulled snowplows through the drifts in order to speed up the process. In places where drifts were too high, workers dug tunnels for residents to walk through. In the days after the storm, temperatures quickly rose and the snow melted away in a few short weeks. Sadly, the melt uncovered the bodies of some of the state’s missing residents.

Jeannine Henderson-Shifflett, whose work includes curating several exhibits at the New Britain Youth Museum and researching and writing a walking tour for Connecticut Landmarks, holds a graduate degree in Public History from Central Connecticut State University.