By funding a new state house for New Haven in 1827, the General Assembly continued the two-capital tradition. Designed by noted Connecticut architect Ithiel Town, its Greek Revival architecture was intended to recall the beginnings of democracy in ancient Greece.

The General Court

After six futile attempts, in 1828 the General Assembly finally amended the Constitution to end the practice of statewide election of Senators. Eighteen to 24 senatorial districts were created. These new districts, approximately equal in population, provided the first proportional representation since the Fundamental Orders. No changes were made in the House’s town-based system of representation.

Absent from one another much of the year, legislators were in almost constant contact during the legislative session. For a month each year, legislators filled the boardinghouses and hotels of Hartford or New Haven, often sleeping four in a room. Since there were no legislative offices, a directory for each session gave the local address of each member.

Advocates for Equal Rights

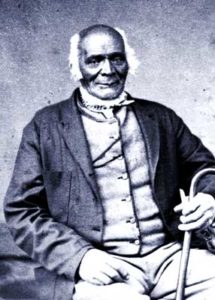

Equal rights advocate, James Mars

Opened in 1833, Prudence Crandall‘s school for “young ladies of color” in Canterbury was fiercely opposed by fellow townspeople. The General Assembly responded by passing a “Black Law” designed to close the school. Crandall persisted and was tried and convicted for violating the law, but the verdict was set aside by the Court of Errors. Her school was later attacked by a mob and she abandoned her crusade.

Deacon James Mars, a leader of Hartford’s African-American community, was born a slave in Norfolk, Connecticut in 1790 and did not win his freedom until 1815. In 1842, Mars and other African-American residents of Hartford petitioned the General Assembly to remove the word “white” from the voter eligibility clauses of the State Constitution and give African- American men the right to vote. The legislature rejected their request for equal voting rights but did finally abolish human servitude in Connecticut in 1848.

The terrible casualties of the war divided public opinion in Connecticut. Democrats bitterly opposed Lincoln’s policies and urged reunion with the South. Their “peace candidate” for governor, Thomas H. Seymour, lost the 1864 election by less than 2,600 votes.

This article is a panel reproduction from An Orderly and Decent Government, an exhibition on the history of representative government in Connecticut developed by Connecticut Humanities and put on display in the Capitol concourse of the Legislative Office Building, Hartford, Connecticut.

<< Previous – Home – Next >>