By Peter P. Hinks

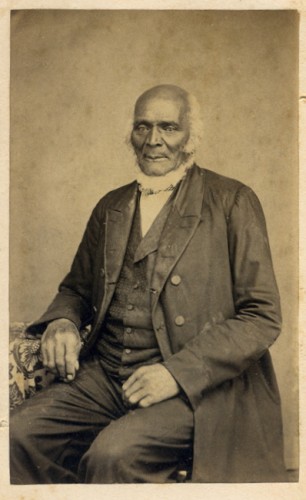

James Mars was born into slavery in Canaan, Connecticut, in 1790. Reverend Thompson, the town’s Congregational minister, owned Mars’ parents and siblings. James, however, was born as Connecticut began to gradually abolish slavery. His memoir, first published in the mid-1800s, stands as one of the most important account of the cruelties and uncertainties of life for the enslaved in New England. Mars’ later life as a free man, political activist, churchman, and autobiographer speaks to the importance of historical memory—of remembering the ugly truths as well as accomplishments of the past.

Life under Gradual Emancipation

The enslavement of African peoples had been present in Connecticut since the 17th century, and by 1775 slaves in the state numbered almost 5,100, roughly 3% of the population. In 1783 the General Assembly passed a gradual emancipation act, which would take effect on March 1, 1784. From that date, all children born to enslaved parents would be free upon reaching their age of majority—25 for men, 21 for women. While the enslaved could not be sold out of state, they were to labor faithfully for their mother’s owner who could sell them to work for another master or mistress until they reached the requisite age to be freed. James thus came of age as the presence of slavery steadily diminished in the state.

Nevertheless, James remained in the custody of Thompson, who in the latter 1790s decided to remove to Virginia and to take the Mars family with him. Once the family realized his plans, they fought tenaciously to circumvent them. Fleeing to the nearby town of Norfolk, Connecticut, James’ parents found local white supporters who hid the family and would alert them when Thompson or his agents prowled the vicinity. Over the next several years, they lived, worked and roamed furtively in and about the households and woods of Norfolk. They narrowly averted recapture on several occasions.

By 1798, Thompson had managed to place Mars with another family in Canaan. Yet by September of that year, the reverend grew eager to move to Virginia and tired of tracking the Mars family. Thompson arranged through intermediaries for James to be sold to a Mr. Munger of Norfolk and for his brother to be taken on by another local slave owner. While both of James’ parents and his sister secured their manumission and remained in the Norfolk area, he and his brother would have to remain with their respective owners until they reached the age of 25.

Munger proved to be an abusive taskmaster. Old and frail, Munger worked James long and strenuously in the fields, at woodcutting, and with tending the horses and cattle. Munger “was fond of using the lash,” as James later wrote. James’s brother managed to gain his freedom by the age of 21 and James set his hopes on a similar release. When he turned 21 he went to his parents’ house and refused to return to Munger. The courts eventually intervened and determined that James be freed from Munger upon paying him a compensation of $90. James, however, reconciled with the Munger family after his manumission and returned to work for them for a number of years afterwards.

Mars Wrote to Remind All of Connecticut’s Past as a Slave State

In the early 1830s, Mars married and had two children. The family moved to Hartford where James worked in a dry goods store while becoming very involved in the life of the city’s emerging free black community. He became a deacon at the Talcott Street Congregational Church and a principal in the pivotal case, Jackson v. Bulloch (1837), in which the enslaved Nancy Jackson successfully sued her Georgia owner, James Bulloch, for her freedom.

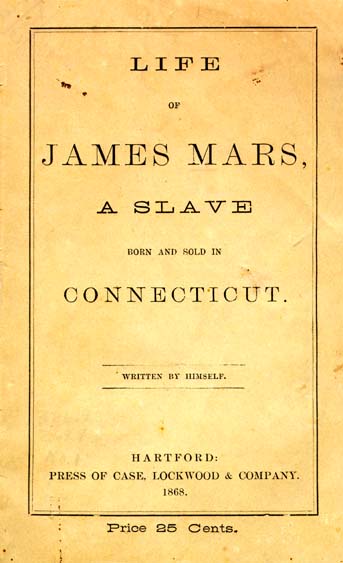

Life of James Mars, a Slave Born and Sold in Connecticut. Written by Himself

In about 1845, Mars moved with his family to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where he purchased land. He farmed, schooled his children and stayed involved with black reform and political movements. One son would later join the US Navy while his daughter would become a colonist in Africa at Cape Palmas, a settlement sponsored by the American Colonization Society.

In 1864, an aging James Mars returned to Norfolk. By 1870, impoverished and increasingly frail, Mars determined to write his autobiography because “[s]ome told me that they did not know that slavery was ever allowed in Connecticut, and some affirm that it never did exist in the State.” He recognized “that the so-called favored state, the land of good morals and steady habits, was ever a slave state, and that slaves were driven through the streets tied or fastened together for market. This seems to surprise some that I meet, but it was true.”

The man who took great pleasure in having been able to vote twice for Abraham Lincoln now resolved to correct the memory of his beloved state. Sale of the thin pamphlet aided him financially in his later years, and local residents later recalled how Mars, hobbled with leg problems, would travel slowly from door to door, selling his powerful testament to an earlier inhumanity in the state. In May 1880, in Ashley Falls, Massachusetts, James Mars died.

Peter P. Hinks is a historian who has researched and written extensively on slavery and black freedom in Connecticut and the American North.