By Steve Thornton

At a “Colored Men’s Convention” in Hartford on January 26, 1899, Connecticut’s first black lawyer took to the stage with an uncompromising message. “It is the right of the colored man to fight for his rights,” Walter S. Miller told the crowd. “When a white man shows a revolver, I want the Negro to show one also. In that way only will he be granted his rights by demanding them and being ready to insist upon them.”

During July 1967, several Hartford children look into a broken storefront window. Many businesses in North Hartford were attacked during the riots, and Hartford, along with Newark, New Jersey, became a national symbol of racial unrest. Photographer Unknown – The Hartford Times Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

From the 1920s to the 1960s, Connecticut’s African American activists formed a number of membership groups for self defense. The Anti-Lynching Crusaders (led by Mary Townsend Seymour), the Negro Defense Council, and the Hartford League of Struggle for Negro Rights were just some of the organizations that protested police and vigilante violence on a local and national scale.

In 1961 the US Civil Rights Commission found that as the civil rights movement grew, a majority of African Americans feared racist backlash. They feared police violence and harassment as well. The commission reported that when racial violence took place, the black community came to expect that “the police will side with the white mob.” The same report found that “Negroes feel the brunt of brutality proportionately more than any other group in American society.”

Divided by Race and Class

In Hartford, Connecticut, downtown separated the black, poor North End from the stable, white working-class South End. The two areas reflected America’s race and class divisions, particularly the wide gap between how Connecticut’s black and white residents viewed the 1960s urban rebellions.

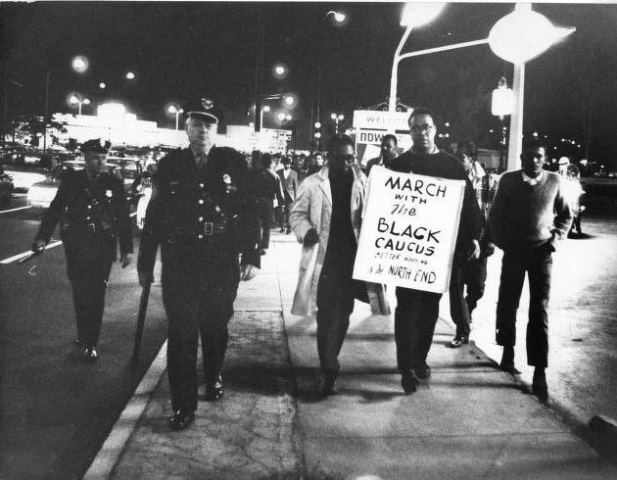

Marchers for better North End (Hartford) housing, West Hartford, 1967. Photograph by S. Robert Pugliese – Hartford Public Library, Hartford History Center, Hartford Times Collection and Connecticut History Illustrated

This racial divide encompassed discrimination in jobs, housing, and education. Police brutality ranked high on the black community’s grievance list as well. Authorities released a confidential analysis of Hartford police/community relations in June 1969 just as they lifted a city-wide curfew, previously triggered by clashes between police and young black men. Respected criminal justice scholar Dr. Sol Chaneles wrote the study at the behest of the local authorities. His “top secret report on crime in Hartford” showed that African Americans believed the Hartford police force spent more time “harassing ghetto residents” than protecting them.

Dr. Chaneles, who previously worked for the US Chamber of Commerce, reported that whites, not blacks or Puerto Ricans, committed the overwhelming percentage of major crimes in the city. Yet according to Chaneles’s report, a “disproportionate amount of time was spent protecting downtown business establishments” from petty infractions. Meanwhile a dozen organized crime rings operated freely. Hartford’s police chief denied every accusation.

The Panthers Organize

In Bridgeport, Josė Rene Gonzalves of California organized the first Black Panther Party chapter in Connecticut. “We have members in thirty seven states and we didn’t get there by killing,” Gonzalves explained. “We got it by organizing and telling people what the problem is. We are dealing with the needs of the Black community.” He soon started chapters in New Haven, Waterbury, and Hartford. After establishing local leadership, national figures like Ericka Huggins came to the state to run political education courses and organize Panther programs. “This is a revolution,” Gonzalves told a Stamford crowd. “It’s a revolution against the system that teaches a man to be less than a man. A revolution against ignorance, fear and hate.” The Panthers’ goal, he said, was to “take the strength from the few and give the power to the people.”

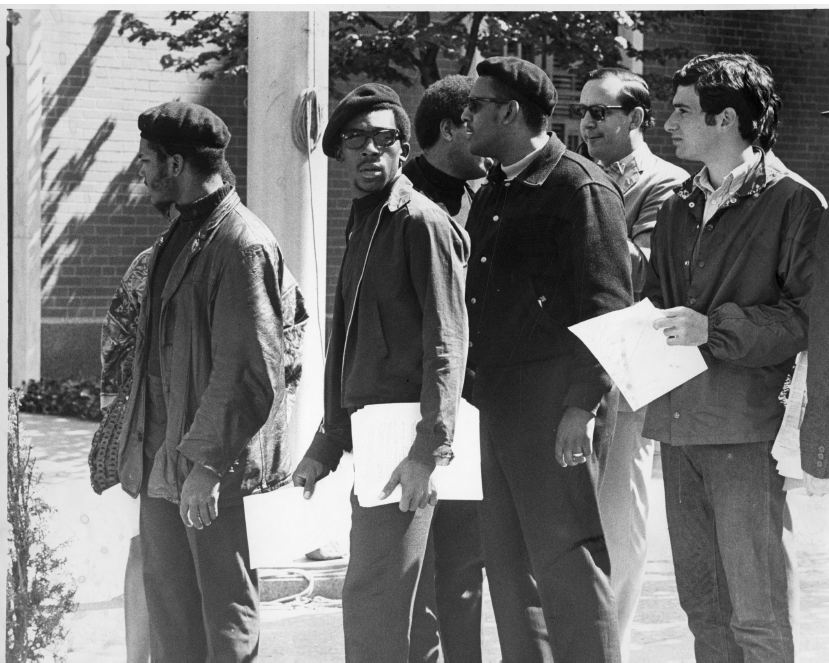

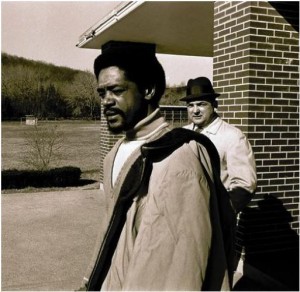

John Barber at Demonstration, Hartford, CT, September 28, 1967 – Photograph by George Grogan – Hartford Times Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

Walter “Rap” Bailey grew up in Hartford. He described how black youths from the projects experienced more violence and deprivation “than any child is meant to see.” His motivation to join the Panthers came after marching with John Barber, leader of the Black Caucus. On September 18, 1967, Barber led protestors on an “open housing” march from the North End to south Hartford. Their target was the practice of segregated housing that made buying or renting homes in the South End practically impossible for African American families. The marchers (an integrated group that included white students from the Community for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) in Voluntown) proved militant but peaceful.

Police stopped the protestors before they reached downtown. Bottles and rocks then began flying through the air, but apparently not from the hands of marchers. Regardless, according to Bailey, police waded into the crowd, hitting and arresting people at random. Word of the arrests spread fast, and that night Hartford experienced its first full-scale riot. When the Panthers started recruiting, Rap Bailey was among the first to join.

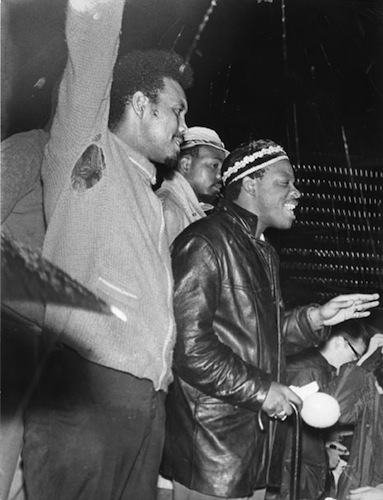

Charles “Butch” Lewis, a well-known and respected figure in the black community, helped organize the Black Panther Party in Hartford. Lewis grew up in the South, moved to Hartford, was drafted and served in Vietnam for 14 months. As a veteran and a respected community figure, he became Field Captain. Lewis understood white people’s perception of the Panthers. “I know a lot of people fear we’re a gang of thugs and hoodlums,” he said during an early Panther demonstration, “but we’re a political party, not a gang. We’re an army of people who are fighting for the people, the oppressed people.”

The Black Panther Presence

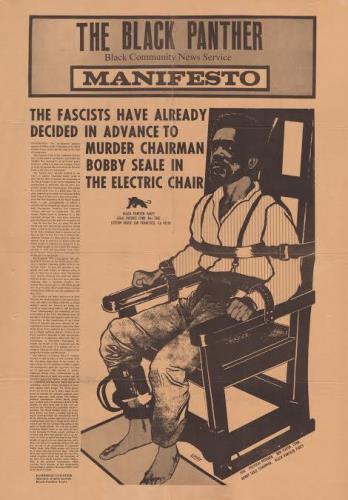

The Black Panther Manifesto. Broadside, 1970. Seale was viewed by some as a victim of a government conspiracy – Connecticut Historical Society

When the Panthers took to the Hartford streets in the summer of 1969, their first priority was to “patrol the police.” Panther leader Don Mounds told a public forum: “What we were doing was patrolling the police for the simple reason that we knew, like a lot of people know, that the police make false arrests, shoot tear gas into the houses. The police came into the area like storm troopers. We were threatened to be arrested and a few of us were arrested.”

Some police officials saw the Black Panther presence, and the party’s use of the Second Amendment to carry arms, as a direct threat to police authority. Yet even when neighborhood groups attempted to protect black lives and property, they found their efforts blocked by local police departments. In Waterbury, Mayor George Harlamon made an agreement with a group of youths (who called themselves the Young Black Militants) to patrol city streets on their own block, equipped only with bullhorns. The police union vehemently objected, declaring that the mayor had “sold out the police department.” On the first two nights of civilian patrol, however, one officer admitted that it was the quietest time on the streets he had ever seen.

Hartford residents faced the same resistance. The Oakland Civic Association formed an unarmed patrol of men to watch their neighborhood. This effort had some funding behind it and the men wore berets and carried whistles and walkie-talkies. The Hartford police forced the men to abandon their berets and equipment, but still, disturbances dropped significantly while they patrolled the streets.

Bobby Seale leaves Montville for his trial on March 18, 1971 – Hartford Courant file image

One Connecticut event eclipsed all the work local Panthers undertook, however. In 1969, police arrested 14 New Haven members for the murder of Alex Rackley, a Panther from New York. While the prosecutor called it an “ordinary case of murder,” the trial became a showdown between the federal government and the Panthers. Authorities arrested Ericka Huggins and Black Panther founder Bobby Seale for the crime, which many in the movement believed was part of an effort to disrupt the Panthers’ organizing efforts and force the group to spend all of its time entangled in the legal system. In the end, three men faced conviction in 1971 for Rackley’s murder. The remaining defendants, including Seale and Huggins, were released.

Conflicting Views of the Black Panthers

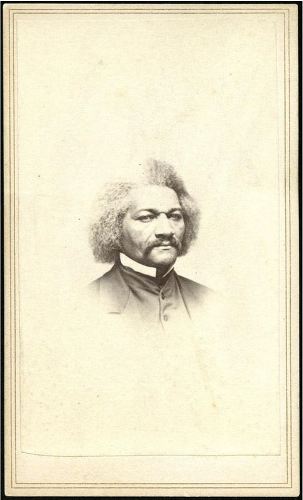

The legendary abolitionist Frederick Douglass spoke in Connecticut many times, including an 1879 talk in Hartford on John Brown (the anti-slavery activist both celebrated and damned for his armed rebellion at Harper’s Ferry). Douglass called Brown a “moral earthquake,” a metaphor that conjured up death and destruction on a righteous scale.

Frederick Douglass. Photograph by Stephen H. Waite, 1864. Taken in Hartford during an 1864 lecture tour – Connecticut Historical Society

Many viewed the Black Panthers in the same conflicting light. Whites often feared and loathed the Panthers, charging them with fomenting violence and being behind much of the 1960’s urban riots. This was not a universal opinion, however: “Violence was there all along in back alleys and ghetto streets,” wrote an international observer. “What the Panthers did, by standing up armed, was to become lightning rods attracting those flashing bolts of violence, and the concentration of fire power coming from police guns lit up the night.”

Steve Thornton is a retired union organizer who writes for the Shoeleather History Project