By Steve Thornton

“No Danger of Race Riots in Hartford Police Officials Say.” It was August 4, 1919. Hartford’s black clergymen feared that the white mob violence raging through seven US cities could very well take place in their own city. Police chief Garrett J. Farrell tried to reassure the ministers by telling them that “there was no likelihood of a dispute between white and colored residents.” Reports of a racial incident on Windsor Street were probably “phoney,” Farrell said.

Detail from a glass plate negative showing the rear of one of the tenements that lined the Park River, Hartford – Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

The clergy used their pulpits to condemn wanton attacks on black communities in what became known as “Red Summer.” Even as they were preaching, Chicago, Illinois, was in its sixth day of deadly rioting. The trouble began when a white crowd killed a black teenager who, while he was swimming, strayed from the “colored only” part of a lake. While, in the end, there was no significant racial violence in Hartford that summer, it was only a matter of time.

Racial Tensions Build in Hartford

In the first half of the 20th century, local African American leaders and social reformers exposed intolerable living conditions that, some warned, were bound to spark uprisings. Black families lived in the “worst housing conditions in the country,” according to a 1908 report. Child mortality was almost three times higher for black children than for whites (a 1923 Yale health study found) and tuberculosis deaths in blacks occurred with five times the frequency of whites during the 1930s.

In addition, there was “practically universal prejudice” against hiring black workers, a government official told Connecticut business leaders in 1919. Five of the top Hartford factories employed no black men or women.

The Hartford coalition attending the March on Washington for Freedom and Jobs in August 1963 included religious leaders, business leaders, men and women, blacks and whites – Photographer Unknown – Hartford Times Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

As the century progressed, little changed. Every new report or investigation and every prescription for change received lukewarm responses from local government and business leaders.

It was not that reformers always failed. Black activists, often backed by their churches and low-key civil rights groups, led struggles to better their communities. Together, they created housing and other improvement projects. When they politely petitioned government for support, however, they often found themselves politely ignored.

Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes told the nation in 1951 that if the American Dream was deferred for black people, it could “dry up like a raisin in the sun,” or, he warned, it could explode. The barriers to decent living were taking their toll for an ever-increasing number of Connecticut’s African Americans who made their exodus from the South. (Hartford’s black population more than doubled over the next decade—from 12,000 in 1950 to 25,000 residents in 1960.)

On March 11, 1965, a determined group of local leaders met with Hartford’s commission on human relations in another attempt to win urgent action. The NAACP, the Catholic Inter-racial Council, and the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) again laid out the problems facing the black community. A young group of upstarts, the North End Community Action Program (NECAP), was also present. Using the civil disobedience tactics of the southern Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), NECAP had earned its place at the civil rights table.

At the March 11th meeting, both the public and private sectors received harsh criticism. “Negroes are being deprived of basic rights,” said one leader, while others claimed that responses from city power brokers were “a whitewash.” The groups left frustrated and angry. “I hate to think of the demonstrations in Hartford we’re going to have if we don’t get some action,” said a representative of the Catholic group.

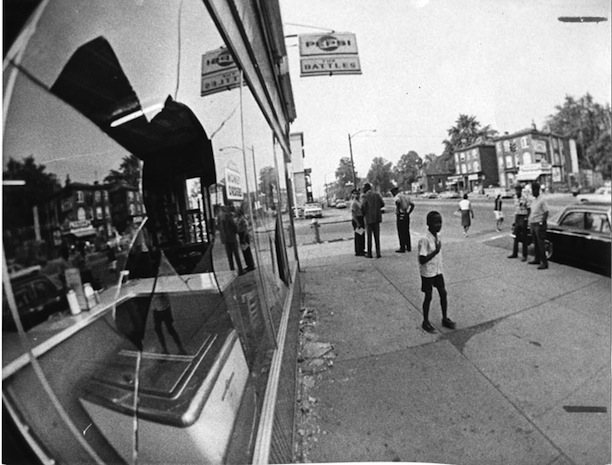

Damage from demonstrations, North End of Hartford, Hartford, CT, July 1967. Photograph by Ellery G. Kigton – The Hartford Times Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

Frustrations Become Disobedience

New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago had all been scenes of urban rebellions in 1964. Now, a few months after the disappointing March 1965 meeting in Hartford, the Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts lay burning. On the warm night of August 17, 1965, NECAP director Charles Turner told a crowd of 300 that the Watts uprising was triggered by the same conditions that faced Hartford’s poor. A sign in the crowd even read, “Turn Left or Be Shot,” a direct reference to the National Guard order given to Watts protest marchers.

The NECAP-led crowd then marched down Main Street to city hall. Officials bused in thirty police officers to meet them. As Turner and others attempted to bring a symbolic black coffin to the city hall steps, a police line blocked their approach. After trying to cross the line and sit on the steps, Charles Turner and eight others found themselves under arrest. They were ultimately convicted of incitement to riot.

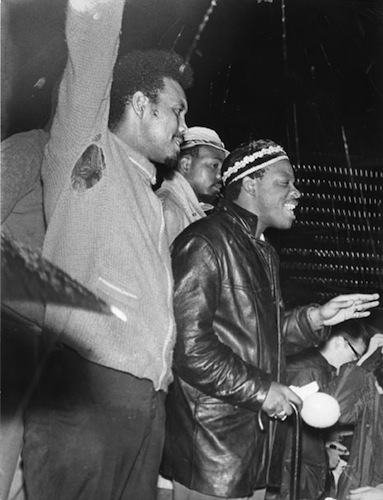

John Barber (spokesman for the Black Caucus) at a local demonstration, Hartford, CT, September 28, 1967 – Photograph by George Grogan – Hartford Times Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

Word traveled fast through the north end that night. Soon a crowd gathered at the original rally site. The police blocked access to the area. A few bottles and rocks thrown into the streets accompanied the arrest of 14 more people.

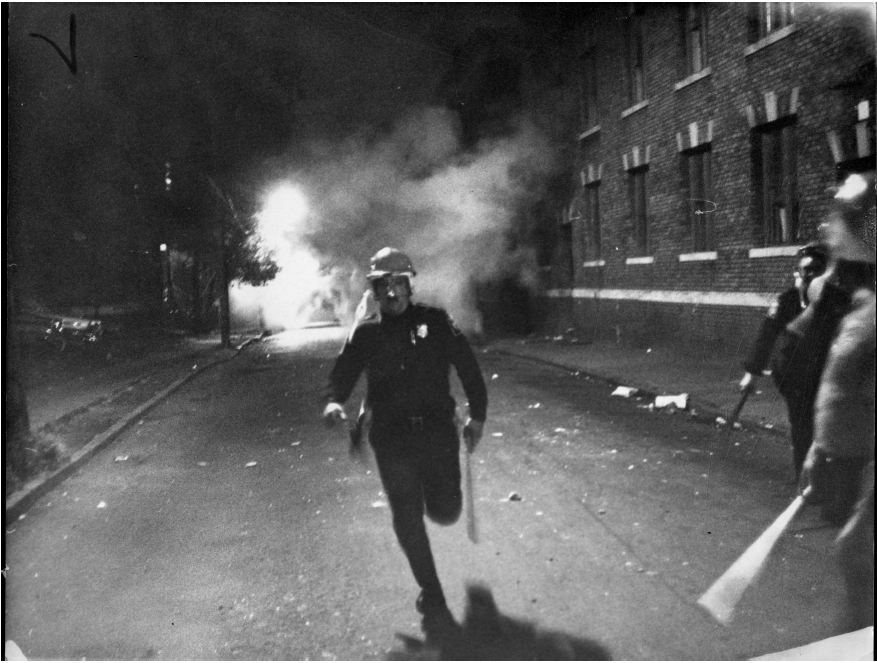

Over the next five years, Hartford’s north end exploded. On July 12, 1967, the arrest of a black teenager for allegedly swearing at a waitress led to charges of police brutality. Four nights of rock-throwing, broken windows, and arson ensued. One well-known black conservative blamed “engineers of violence” who were supposedly directing the street disturbances. Not everyone believed the “outside agitator” theory, however. As Martin Luther King Jr wrote, “A riot is the language of the unheard.”

April 4, 1968, witnessed the assassination of Dr. King. Grief and anger once again turned into violence. Much more attention was paid to the street disturbances, however, than to the 400 Hartford High students who peacefully marched downtown from their school to talk with the mayor.

Connecticut Politicians Embody National Divisions on Race

American society never reached a consensus on either the cause or the solution to the urban revolts. Nowhere was this more evident than in the opposing positions taken by Thomas J. Dodd and Abraham A. Ribicoff, two Democratic senators from Connecticut during the 1960s.

US Senator Abraham A. Ribicoff, far left, and US Senator Thomas J. Dodd, second from left, met with Connecticut men and women attending the March on Washington for Freedom and Jobs on August 29, 1963. An estimated 3,000 people from Connecticut were at the march. Photographer Unknown – Hartford Times Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

Senator Ribicoff believed that the cause of the riots stemmed from “100 years of neglect” of the black community’s needs. When he said “black Americans are now presenting the consequences to the nation” of that neglect, Senator Dodd (who called riots “an incipient civil war” targeted at whites) insisted the riots were the work of “black extremists” controlled by Red China and Fidel Castro.

In addition, Ribicoff argued that part of the problem was the $30 billion a year spent on the Vietnam War, which he felt siphoned off money badly needed by cities. To the contrary, Dodd declared the US was “strong enough” to prosecute the war and run the country at the same time. Finally, while Senator Ribicoff submitted a $1 trillion spending bill for housing and full-employment programs, Senator Dodd authored “riot control” legislation to establish a 20-year prison term for crossing a state line to incite a riot.

The debate in Connecticut proved symbolic of just how divisive an issue urban riots proved to be for the entire nation. Dodd and Ribicoff, while both desirous of restoring peace to inner city neighborhoods, proved remarkably far apart on their approaches to understanding and addressing racial unrest in America.

Steve Thornton is a retired union organizer who writes for the Shoeleather History Project (shoeleatherhistoryproject.com)