By Richard DeLuca

During the last decades of the 19th century, as the railroad established itself as the dominant form of overland transportation in Connecticut, events were in motion that would undermine its future and alter the direction of transportation for generations to come. The agent of change was a modest new technology in whose popular success Connecticut played an important role: the bicycle.

The Extraordinary “Ordinary”

In 1878, Colonel Albert Pope, a former Civil War officer and successful entrepreneur from Boston, began the manufacture of what was called the high mount or “ordinary” bicycle at the Weed Sewing Machine Company in Hartford. Pope had first seen the ordinary bicycle, an English import, at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia two years earlier. Despite the difficulties of riding a cycling machine with a front wheel 54 inches in diameter and rear wheel less than half that size, Pope was determined to make the ordinary bicycle an American success story. To that end, he acquired the patents needed to legally control the trade in this country and within a few years was producing 10,000 bicycles a year from the Capitol Avenue plant in Hartford, which he now owned.

The Columbia Cycle Club, Hartford, 1890 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

As the popularity of cycling grew, bicycle clubs appeared in cities across the country, including Bridgeport, Hartford, and New Haven. In 1880 Pope, a businessman who knew the value of product advertising, convened a meeting of 31 cycling clubs in Newport, Rhode Island, and formed the League of American Wheelmen, a national organization with state chapters that acted to promote bicycle touring among those daring enough to undertake the challenge of an ordinary bicycle.

As a result, a social network of cyclists evolved in many states, including Connecticut, where the league produced its first Connecticut roads book in 1886. By 1890, the pocket-sized Cyclist’s Road-Book of Connecticut had been revised to include more than a dozen suggested cycling tours and fold-out highway maps, with recommended routes highlighted in red, for each of Connecticut’s eight counties. Each route segment was rated in increments, from poor to first class, for the condition of the roadway as well as its grade, from level to very hilly. In addition, the league held annual tournaments in Hartford and New Haven, where ordinary cyclists gathered to race, share adventures, and celebrate their sport. For the cycling league, it was an opportunity to recruit new members. Together with a road book of recommended touring routes, membership included discounts at certain hotels and restaurants along the way.

Woman wearing bicycling costume, Pope Manufacturing Co., package enclosure, Hartford, 1895 – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

A Better, Safer Bicycle

The relatively high cost of an ordinary bicycle and the physical stamina required to use it, however, limited the market to athletic young men of the middle and upper classes. Yet by 1888, advances in metallurgy, gearing, and pneumatic tires produced the low mount or “safety” bicycle. With smaller, equally-sized wheels front and back, and an optional drop-bar frame for lady-like mounting, the safety bicycle opened the sport of cycling to nearly everyone, while mass production lowered the price to an affordable $75. Within 2 years, the number of cyclists in the United States doubled to 150,000, many of whom were women. As a travel writer passing through Saybrook, Connecticut, in 1902 noted of that community:

An odd thing about the town, and one that rather offset its sentiment of antiquity, was the omnipresence of bicycles. Everybody, old and young, male and female, rode this thoroughly modern contrivance. Pedestrianism had apparently gone out of fashion, and I got the idea that the children learned to ride a wheel before they began to walk.

Good Roads for Smooth Riding

As the cycling craze grew, the role of the League of American Wheelmen expanded to include a national campaign for the construction of good roads, especially of inter-city country roads, which were often poorly maintained by the compulsory labor of town residents. As a member of the league’s national executive committee, Albert Pope became a relentless advocate for good roads, using his own funds to establish the league’s Good Roads magazine and to endow courses in highway engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. To broaden the scope of the issue beyond cycling, Pope gave numerous speeches on the economic benefits of good roads to groups such as the National Carriage Makers Association and the Hartford Board of Trade, and in 1892, he founded another lobbying organization, the National League for Good Roads.

Pope’s advocacy proved effective on both the national and state levels. Following a petition to establish an ongoing national program for road improvement, Congress established the Office of Road Inquiry in the US Department of Agriculture in 1893. The office disseminated information on good road engineering and built short segments of “object-lesson” roads in select cities to whet local appetites for additional good road construction.

While the Office of Road Inquiry did not plan or fund a national network of good roads (that would have to wait for its successor, the Bureau of Public Roads, and the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1916), it became a permanent presence in the national government and replaced the League of American Wheelmen as the chief lobbyist for good roads.

States Get into the Act

The good roads movement initiated by Pope and the League of American Wheelmen impacted state governments as well, as the heavily traveled Northeast established the first highway departments in the nation. The Connecticut program, established in 1895, evolved into a cooperative venture between individual towns and the state government, with towns funding from one-quarter to one-third the construction cost of road improvements, while the state provided the remainder.

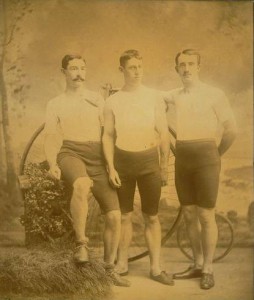

The Hartford Wheel Club racing team, Hartford, 1886 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

By the late 1890s, the state budget for good roads was $250,000 annually, enough to improve perhaps 80 miles of road each year. It was a slow start, but funding gradually increased. By 1905 the Connecticut Highway Department had identified a statewide system of trunk line highways (a scheme to handle long-distance through traffic) that totaled about 1,000 miles and whose improvement and ongoing maintenance was the state’s sole responsibility. State (and eventually federal) funding of highway improvements represented a radical departure from past transportation policy, in which all manner of improvements—from turnpikes and steamboats to canals, railroads, and street railways—had been provided by privately owned corporations. The change in policy had been prompted by the latest in a long line of transportation technologies, the bicycle, and by men like Albert Pope.

No sooner had the state funding of good roads begun when another new transportation technology appeared. In 1893, Frank and Charles Duryea drove their gasoline-powered horseless carriage on the streets of Springfield, Massachusetts. Though at this early date no one realized the impact that the horseless carriage and the coming age of automobility would have on the railroad and other modes of transport, Albert Pope sensed the timeliness of the event and what it meant for the future of the good roads movement. “The advent of the motor-carriage,” he noted, “is bound to increase the interest in good roads. The day of the horse is already beginning to wane, and as soon as a practical motor-carriage can be had by men of moderate means we must have good roads, not only in and about the cities, but throughout the entire country.”

Richard DeLuca is the author of Post Roads & Iron Horses: Transportation in Connecticut From Colonial Times to the Age of Steam, published by Wesleyan University Press, 2011.