By Amy Gagnon for Connecticut Explored

The town green remains a quintessential and unique part of the New England landscape, and for those towns lucky enough to have one still, the green may be one of the only extant artifacts from colonial times. An impressive 170 Connecticut greens exist today, though some towns have more than one and some no longer—or ever did—have any. Today, we re-appreciate the town green as a place where communities come together in times of celebration and commemoration. Three Connecticut towns—Lebanon, Newtown, and New Haven—have particularly notable greens.

Plotting the Green

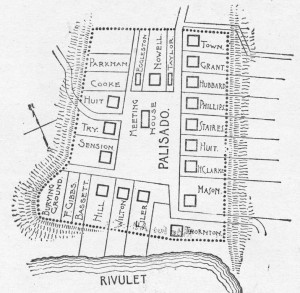

Plan of the Palisado, the original layout of the town of Windsor – Windsor Historical Society

As English settlers laid out Connecticut’s earliest towns in the 17th century, they reserved the best land for planting and for animals to graze, then plotted land close by on which to build their homes, often on equal-sized plots. In the middle of their settlement they reserved a common area for public use and as a place to erect a meetinghouse. While some planned settlements were regular in arrangement, more often they were irregular tracts shaped by topography and burgeoning town development.

Many early town greens served as the physical and spiritual centers of towns. In addition to serving as sites for religious activities—meeting houses stood on the green—they were multipurpose public gathering places, market places, parade grounds, places for local citizens to report for military training, burying grounds, and grazing areas for cattle or sheep. With their stocks and whipping posts, they were also sites of public punishments. Furthermore, townspeople used town greens as dumping grounds for discarded household items and broken equipment. With all of that going on, the green was not the peaceful, park-like place that we are familiar with today. Rather, as a heavily used communal space, the ground was often muddy, rutted from wagon wheels, and dotted with tree stumps and large rocks they had not bothered to remove. It was not until after the Revolutionary War that the town green began its transformation into the picturesque place we revere today.

The Town Green Gets a Makeover

Broadside announcing a lecture by Professor B. G. Northrop on the subject of village improvement, March 26, 1878, Glastonbury – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

In the decade after the Revolutionary War, population growth in Connecticut and the rise of industry provided new economic prospects for townspeople. Improvements in transportation, land grading, path and road construction, and communication led to greater ease of travel, and those who lived far from town centers, or in other towns altogether, could more easily journey greater distances to sell their goods. Residents cleared their greens of clutter and debris and arranged commercial and civic buildings around the edges, thus transforming many Connecticut greens and adjacent areas into thriving pre-urban commercial and civic hubs.

Starting after the Civil War and continuing into the late 19th century, residents increasingly viewed town greens as important central areas for shared community life. With the industrial age in full swing, people wanted a respite from the increasing crowdedness of city life, and when the City Beautiful movement swept through New England in the late 19th century, many ordinary greens in bustling city centers evolved into landscaped parks with trees, paths, street lamps, and benches. Greens also began to serve as places in which to erect war memorials.

In smaller towns, residents—mostly elite townswomen—established village improvement societies to beautify town centers and greens. They raised funds by holding bake sales and by soliciting unofficial taxes from property owners whose lots fronted the green. In 1845 residents from the town of Thompson raised funds to plant elm, maple, and ash trees on the green, and the loosely organized village improvement society saw to the green’s upkeep. Formally organized in 1874, Thompson’s village improvement society still maintains the land. By the turn of the 20th century residents of New Britain turned their town green into a small public park, now known as Central Park, which the city’s parks commissioner controlled. The green, located in the heart of downtown, maintained its original form as the downtown area developed around it.

Lebanon’s Revolutionary Green

Of all of the town greens throughout Connecticut, perhaps the most expansive and best preserved in its colonial form is Lebanon’s town green. Lebanon is located in the northernmost part of New London County and has largely maintained its agrarian roots. Most of present-day Lebanon was established in stages, beginning with a land grant from the General Court to John Mason in 1663 and continuing with the Five Mile Purchase in 1692 by English colonists of the Norwich area from the Mohegan sachem Oweneco. Around the time of incorporation in 1700, Lebanon resident Joseph Trumbull (father of Colonial governor Jonathan Trumbull Sr.) introduced livestock farming to the town. Thus began Lebanon’s long farming history.

By 1730 all available farm plots had been distributed to 51 original proprietors. In the center, an expanse of land two miles long by 400 feet wide was set aside as the town green. The town authorized a highway to run through it, and along the highway they built the meetinghouse and school. They used the green to pasture animals, train militia, and serve as the marketplace.

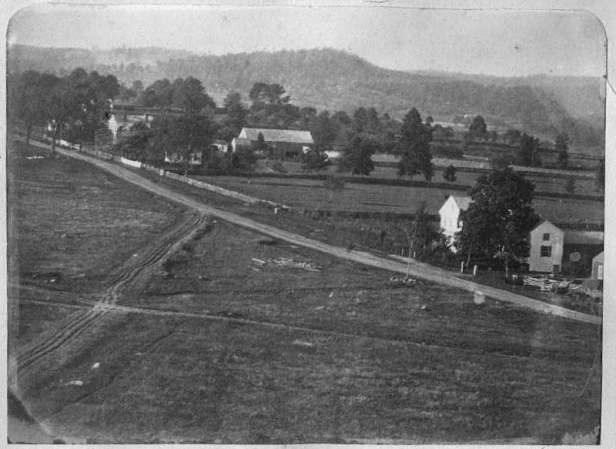

East Town Street and green viewed from the steeple of the First Congregational Church, 1868, photographer unknown – Lebanon Historical Society

Best known for its connection with the Revolutionary War effort, Lebanon was the home of Jonathan Trumbull, the only colonial governor to support rebellion against England. Trumbull led Connecticut’s mobilization of men and provisions from the War Office located at the edge of the green. The War Office also served as the meeting place for the Council of Safety, a wartime group organized to assist the governor. The Council met at the War Office more than 500 times, and George Washington visited. From November 1780 to June 1781, Lauzun’s Legion, the cavalry unit of the French army, used the green as its base camp and winter headquarters. Both American and French soldiers practiced their drills there.

In the years following the Revolutionary War nearby towns embraced the rapidly growing industrial age and built mills and factories along plentiful waterways. But Lebanon did not follow suit, remaining primarily an agricultural farming community and continuing to use the green for farming and grazing.

Though today the green is smaller than its original size, at one mile long and 400 feet wide it remains the town’s most distinctive feature. It was never landscaped as a park. Since Lebanon lacks a formal commercial district, community life centers on the green. Three of the town’s churches, the town hall, library, historical society, and historic Revolutionary War sites are all located on or near the green. Because of its national historical and architectural significance, the Lebanon Green was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978, along with the Revolutionary War Office and the Governor Trumbull Home that still stand at the green’s edge.

Visitors today experience the green much as it may have looked in the 18th century. While mostly level, the land slopes slightly behind the evenly spaced and deep-plotted buildings at its perimeter. Exactly who owns the green today is unclear. While it rightfully belongs to the descendants of early property owners, it is impossible to trace those titles. Under a remarkably cooperative arrangement, the town maintains responsibility for the land, and local farmers maintain portions of the grounds. The open expanse of land is the only town green in the state that is still used for agriculture: the hay grown there is harvested twice yearly by local farmers. It is through this relationship between the town and residents that the Lebanon Town Green remains preserved as open and public space.

Newtown’s Ram’s Pasture

Located in the southwestern part of the state, Newtown, incorporated in 1711, is a good example of early town planning. Newtown’s Main Street, once known as Town Street, dates back to 1709. When four-acre lots were laid out on either side of the street in a north-south direction the low-lying land to the west of Town Street was reserved for common land, some of which today is known as Ram’s Pasture for the sheep that once grazed in its fields. As early as 1732, town settlers made provisions for this large expanse of land to be reserved as a common grazing area for their collective flocks. But by the end of the 18th century, landowners had claimed and divided up much of the common land.

As with Lebanon and other towns across the state, troops under French General Rochambeau camped on Ram’s Pasture on their way to meet General Washington in Yorktown. Throughout the 19th century, the 12½-acre green remained undeveloped and under individual ownership. Then, in the 1920s, long-time Newtown resident and philanthropist Mary Hawley purchased the green from its various owners. The land briefly went to Yale University as part of Hawley’s estate after her death. In 1931 the Newtown Village Cemetery Association acquired the land and continues to maintain it today.

A Plan of the Town of New Haven with All the Buildings in 1748 by James Wadsworth. New Haven, CT: T. Kensett, 1806 – University of Connecticut Libraries, Map and Geographic Information Center (MAGIC) from the Map Collection, Yale University Library

Today, Newtown’s Ram’s Pasture is a long, broad meadow between South Main Street and Elm Drive. A brook runs through the meadow’s center to a pond at its south end. Trees dot its east end, and its landscaped area is well tended—a contrast to the rest of the meadow, which remains in a natural state. During the 19th and 20th centuries the neighborhood around Ram’s Pasture turned residential. Today, much of the land serves as a park for public events, such as the town’s annual Christmas tree lighting, and though not technically a formal town green, Ram’s Pasture retains much of its colonial character.

New Haven’s Green

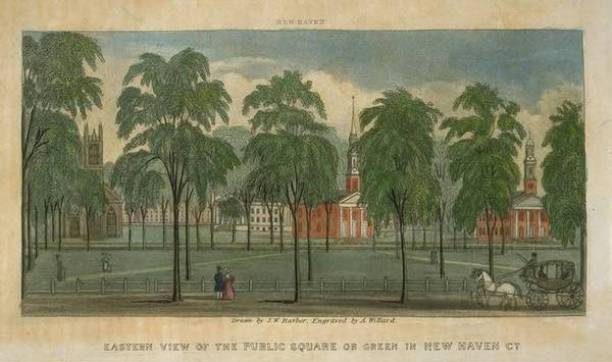

New Haven’s settlement began in 1638 when a company of English colonists led by merchant Theophilus Eaton and the Reverend John Davenport arrived from Boston. By 1641 the new town was laid out on a nine-square grid plan measuring a half-mile square. The center square, in keeping with English custom, was reserved for a green, while the eight surrounding squares were designated as house lots. On the green, town leaders built the meetinghouse and burying ground, the jail, and the town’s first school. They also used the common area as a market place and trade center for goods entering the bustling nearby port and as parade grounds and a mustering place for troops. New Haven and Hartford became co-capitals of the colony in 1701, and in 1719 founders erected the state house on the green’s northwest side (demolished in the 18th century to make way for a new capitol, which was in turn demolished in the late 19th century).

While other early settlements took utilitarian approaches to managing their common areas, New Haven’s early residents had an eye for beauty. They planted grass as early as 1654 and shade trees in the 1750s. Jared Eliot, in his 1760 paper “Essay on Tree Planting,” mentioned New Haven’s trees, writing, “I observed in New Haven they have planted a range of trees all around the market place and secured them from the ravages of beasts. This was an undertaking truly generous and laudable.”

Drawn by John Warner Barber. Engraved by Asaph Willard, Eastern view of the Public Square or Green in New Haven, ca. 1849, wood engraving – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

By the early 19th century, city officials continued to improve the green, fencing it off from the growing city around it and adding park-like improvements such as sidewalks and shade trees. Three of the city’s churches built new structures on the green at Temple Street, and a new state capitol building designed to resemble a Greek temple was erected on the upper green. That building was demolished in the late 19th century. In 1861, noted architect Henry Austin designed the Gothic Revival City Hall on Church Street facing the green. By the early 20th century, beautification efforts provided the impetus for building the 1908 New Haven Free Public Library and the 1914 New Haven County Courthouse, both facing the green at Elm Street. These large monumental structures complemented the landscaped green and the built environment around it.

Well cared for and obviously revered by its residents, the New Haven Green served as a very early burial ground, and many New Haven residents found their final resting place in the green. The practice of burying the dead there, however, practically ceased around 1800 when James Hillhouse, along with 30 others, purchased six acres on nearby Grove Street in 1796 to form a new burying ground. The first interment there took place in 1797. In 1812 Mrs. Martha Whittlesey was the last one interred in the green; she was laid to rest beside her husband, the Reverend Chauncey Whittlesey. In the same year headstones were cleared from the green, many of them moved to the new Grove Street burying ground, but the bodies were left undisturbed. According to information provided at the Center Church crypt, where many headstones and a few remains from the green now reside, an estimated 5,000 to 10,000 early residents, including New Haven co-founder Theophilus Eaton and Benedict Arnold’s first wife Margaret Mansfield, are still interred there.

Church Street project area and New Haven Green, Air-o-graph ca. 1959 – New Haven Museum and Connecticut History Online

During the 1950s New Haven became a leader in urban renewal efforts, and much of the city became a target for demolition and rebuilding. City planners largely spared the green. Surrounded by the main arteries of Chapel, Church, Elm, and College streets and bisected by Temple Street, the green today retains much of its integrity and many of its original characteristics. The descendants of the city’s original proprietors privately own the present 16-acre green. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970, the New Haven Green continues to be a place for public assembly (in 2011 it was the site of Occupy New Haven), local concerts, and rallies and a public park where people can enjoy open land and tranquility in a densely built urban area.

Whether in a bustling city, a quiet farming town, or a bedroom community, the town green continues to figure prominently in our neighborhoods and in our minds. Be it a small manicured park, a rolling meadow, or a vast expanse of land in the center of a city, the town green is a slice of our tangible past, wholly New England. Next time you drive by a town green, think of it as a window into our colonial past—and every era since.

Amy Gagnon, formerly a Research Historian with Connecticut Humanities, was a member of the ConnecticutHistory.org editorial team and received her MA in public history from Central Connecticut State University.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 10/ No. 2, Spring 2012.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.