By Susan P. Schoelwer

What is a tavern sign? The term designates a popular category of early American folk art, typically consisting of a wooden signboard painted on both sides with a combination of images and words and equipped with hand-forged, often decorative, iron hardware for hanging. Tavern signs originated from the practical need to identify dwellings licensed to provide entertainment to travelers–entertainment being the period term for essential services, including food, drink, and lodging, as well as feed and stabling for horses.

Signs Distinguished Public Houses from Private Homes

Today’s comparable establishments (roadside restaurants, motels, gas stations) are generally recognizable as distinctive building types, but colonial taverns and inns were literally “public houses.” These were ordinary dwellings licensed to accommodate strangers. How could an out-of-towner find such a home-away-from-home? From 1672 on, every licensed innkeeper in Connecticut was required by law to mark his or her establishment with “some suitable Signe set up in the view of all Passengers for the direction of Strangers where to go, where they may have entertainment.”

What was considered a suitable sign? The legislation provides no clue, and no examples or images of 17th-century Connecticut tavern signs have survived. In this early period, it is possible that the presence of any sign in front of a residence was sufficient to distinguish a public house from a private one. The survival rate of tavern signs is extremely low, which is not surprising given the hard usage they received from the outdoor conditions in which they were necessarily displayed. A conservative estimate, based on the number of licensed taverns, suggests that there may have been as many as 5,000 tavern signs produced in Connecticut between 1750 and 1850. Of these, only about 100 (2%) are known to have survived; nearly 70 of these survivors are preserved at the Connecticut Historical Society (CHS) in Hartford.

Documentation is Key to Studying These Artifacts

Although tavern signs have been celebrated enthusiastically as a genre of folk art, they have been difficult to study historically. Most tavern signs have multiple paint layers, having been repainted when surfaces were worn by exposure to wind and rain or when taverns changed hands. A visible date is not necessarily a reliable indicator of a sign’s creation date. In addition, tavern signs collected as folk art can often be identified only in very general terms—for example, as American works produced in the 19th century. Many of the early collectors of tavern signs saw them as representative of an essential American spirit. This national, but anonymous, spirit was more important to such collectors than specific details about who had owned a particular sign or the location of the public house it identified. Such information, which is part of what curators call an object’s provenance, was frequently lost.

In contrast, the CHS collection is not only the largest assemblage of early American tavern signs in existence, but it is also strongly documented, thanks to Hartford insurance company president Morgan B. Brainard. A descendant of Hartford’s founding families, Brainard began collecting signs in the 1920s, focusing specifically on Connecticut examples (although a few outliers unintentionally crept in). Because Brainard’s interests were primarily antiquarian, the vast majority of his signs have histories linking them to specific towns and often to individual owners, whose active dates can be determined from tavern licenses, newspaper advertisements, and other primary documents. The geographic focus and strong documentation of the CHS collection make it an unparalleled resource for understanding the production, use, and significance of tavern signs not only in Connecticut but throughout the United States.

Changing Shapes and Images

Tavern signs were multi-media creations, incorporating three distinct craft traditions: woodworking, painting, and metalsmithing. Surviving signs from the 1700s are characterized by relatively complex, sophisticated woodworking and relatively simple, unsophisticated painting. This pattern corresponds to the profusion of established woodworking shops at the time contrasted with a scarcity of trained painters. Nineteenth-century signs tend to have simpler woodworking but more complex and accomplished imagery. Hardware design is the most difficult of the three components to characterize, as the original elements are often lost or replaced.

Eliphalet Chapin (wood work), Bissell’s Inn post-and-rail sign, South Windsor, ca. 1777 – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain.

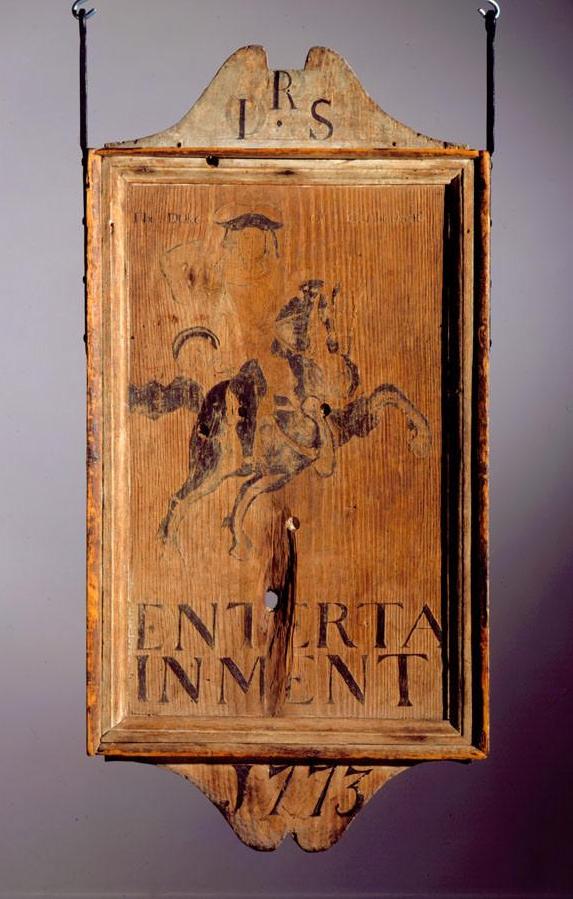

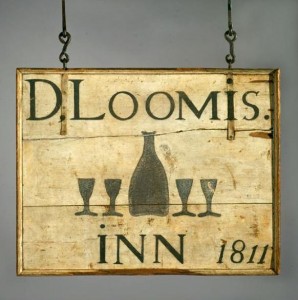

The most iconic tavern sign form is the 18th-century post-and-rails type. This type consists of two vertical, turned posts and two horizontal, molded rails that together frame a vertically-oriented signboard with straight sides and a decoratively-shaped top and bottom (called the pediment and skirt). A related, but less elaborate type retained the shaped pediment and skirt but replaced the post-and-rails framing with four strips of molding nailed directly onto the signboard. An example of this is the Duke of Cumberland sign shown on this page. An even simpler type of sign was likely the most common; this type consisted of a plain panel, rectangular or square in shape, either unframed or framed by applied moldings. This inexpensive type was likely less substantial, less likely to survive hard usage and less appealing to early collectors, leading to a lower survival rate. Thus, the distinctive profile of the post-and-rails type came to epitomize the genre, while the simple panel type is known only pictorially and through later examples such as the sign for David Loomis’s Inn.

Three-dimensional figures, used to mark British inns from the late Middle Ages onward, were evidently rare in America: only two three-dimensional signs from Connecticut are known, both depicting the Roman god of wine, Bacchus.

Stylistically, 18th-century tavern signs paralleled fashions in furniture and architecture. The crowned pediment of the earliest surviving Connecticut sign, dated 1749, for Edward Bull’s Centerbrook tavern, echoes the tops of Baroque high chests and Queen Anne chairs. Later sign-makers adopted the triangular and swan’s neck pediments seen on Chippendale-style furniture and door frames. Elaborate turnings on the posts grew simpler, sometimes becoming classical columns. During the Federal era, around 1800, the popularity of neo-classical designs prompted the replacement of solid vertical signboards with separate panels—either oval or shield-shaped—which were suspended from shaped horizontal rails. With the exception of a brief vogue for oval signs in the 1830s, the majority of post-1820 tavern signs were simple, horizontal rectangles, often with heavy applied moldings, making them appear as outdoor counterparts to painters’ indoor, framed canvases.

From Markers to Marketing, Sign Imagery Grows More Elaborate

The Duke of Cumberland shaped tavern sign, Rocky Hill, 1753 – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain.

Whatever their shape, signboards were painted on both sides and hung for maximum visibility–usually from a crossbar atop a high post or from a horizontal wooden bracket extending outward from the side of a house. Colonial-era signs customarily displayed a single large image above a brief legend, typically the innholder’s initials, a date (usually the year a license was first granted), and sometimes the word “entertainment.” The words “inn” or “tavern” rarely, if ever, appear on extant signs from the 1700s. Surviving imagery includes horses, soldiers, suns, birds, coats of arms, ships, bulls, and saddles; newspaper accounts and other documents record countless other motifs.

The early years of the new Republic saw eagles emerge as the overwhelmingly most popular motif, some based closely on the national seal adopted in 1782. Other choices included allegorical figures, flags, horse-drawn vehicles, moons, suns, lions, grapevines, punchbowls, and decanters. The most sophisticated signs featured portraits, landscape compositions, or genre scenes, often adapted from print sources.

The increased prominence of painted imagery corresponded to changes in transportation, travel patterns, and innkeeping practices, as well as the proliferation of trained, professional artists active in the region. Nineteenth-century turnpikes and stagecoach lines expanded the volume of travelers, changing the nature of innkeeping and the function of signs. Colonial innkeeping had been largely a community service. Especially in small towns and rural areas, it was a sideline– not always lucrative–to the primary occupation of the innkeeper, often a local notable. In this context, tavern signs served simply to inform strangers of available services.

David Loomis’s Inn simple panel sign, Westchester, 1811 – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain.

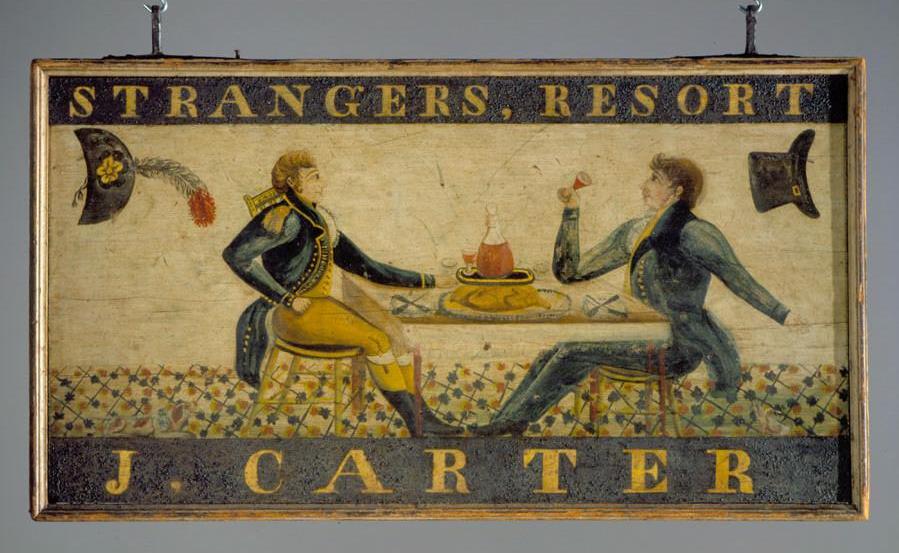

As the volume of travel increased, innkeeping became more commercial. Professional innkeepers aimed to earn a livelihood from the business, competing for customers by emphasizing distinctive offerings. No longer simply markers, signs became potent marketing tools. Squares, compasses, and other Masonic iconography solicited the patronage of traveling Freemasons (and by extension, similarly respectable strangers). Plowshares and beehives invited farmers; anchors resonated with sailors. Where colonial signs repeated the same motif on both sides, 19th-century signs doubled their appeal with different images. Jared Carter’s elegant sign featured a gentleman and a soldier on one side and a fashionable young couple on the other. This imagery explicitly addressed two distinct audiences, even as it visually corroborated its owner’s newspaper advertisements pitching a first-class establishment, a “pleasant and healthful resort” in seaside Clinton.

Sign Painters

The profusion and diversification of imagery on tavern signs in the 1800s was made possible by the increasing numbers of visual artists and artisans active in Connecticut. Signs represented one branch of ornamental painting, which encompassed a wide variety of objects, including carriages, wagons, sleighs, flags and banners, fire engines and buckets, furniture, drums, military regalia of all types, window shades, sleds, woodwork, walls, floor cloths, and floors. More than 60 individuals have been documented as offering sign painting in newspaper advertisements and city directory listings in Connecticut between 1760 and 1850. The number of practitioners was undoubtedly much higher. House and ship painters also painted signs, as did no small number of aspiring portrait, miniature, or landscape artists in need of commissions.

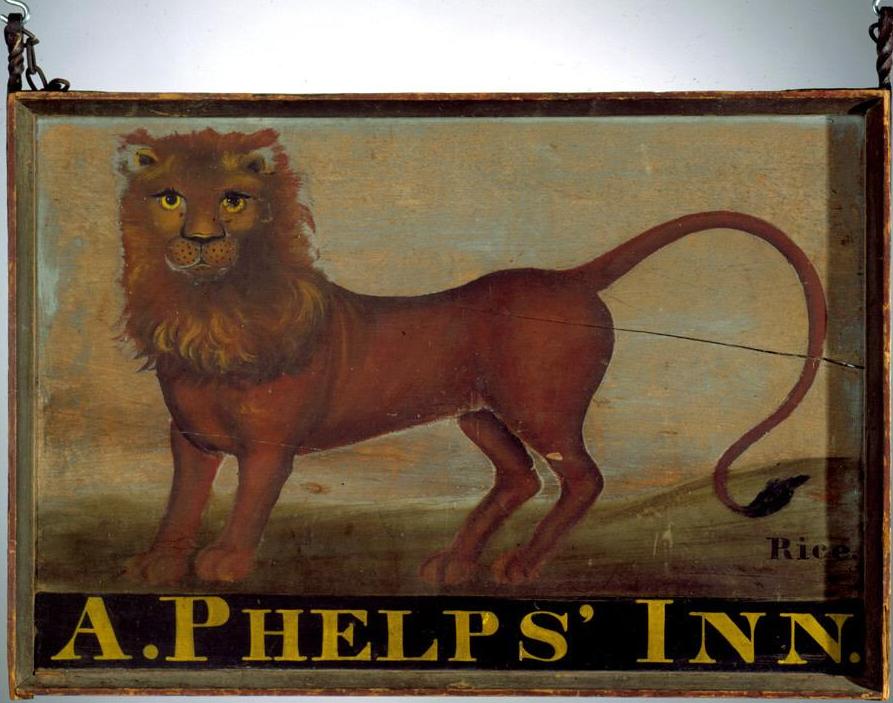

Because few sign painters signed their work, it is rarely possible to link documented artists to surviving signs. One exception is William Rice, who operated a successful painting business in Hartford, at the Sign of the Lion, from 1816 until his death in 1847; the shop was continued thereafter by his son, Frederick F. Rice. At least 20 surviving signs, or 40 compositions, can be credited to the elder Rice—a number much greater than can be linked to any other American sign painter.

William Rice, Arah Phelps’s Inn sign, North Colebrook, ca. 1826 – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Used through Public Domain.

Rice’s painted signature enables the recognition of a characteristic formula, with large, horizontally-oriented signboards framed by deep, heavy moldings. His bold images occupy nearly the entire signboard, with gold-painted black name bands running along the bottom. He offered customers an array of attention-getting special effects: different colors of gold and copper leaf, textured flocking, glittering glass flakes, and glow-in-the-dark smalt. The latter substance consisted of ground-up particles of blue glass, which Rice promised “will never tarnish but grow brighter with age.” Contemporary townscapes showed such signs displayed atop tall posts, visible at long distances, similar to modern gas station or hotel signs along interstate highways.Rice’s most frequent motif was an eagle, appearing in 17 of his compositions. He occasionally paired an eagle with a lion (traditional symbol of the British government); however, no historical evidence has been found to support the common interpretation that Rice intended this pairing as a commentary on the triumph of American republicanism over British tyranny.

A Persistent Tradition

The mid-1800s marked the end of an era in tavern sign painting. Later inn and hotel signs were often little more than name bands, affixed directly to building façades and painted on one side only. Images disappeared, supplanted by an array of ornamental typefaces disseminated in published sign painting manuals. By the 1870s, however, the nascent Colonial Revival movement prompted renewed interest in quaint old tavern signs. Surviving examples were resurrected from sheds and attics and updated to adorn self-consciously old-fashioned country inns and tea rooms. New versions became popular as signs for antique shops.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the primitive qualities of early signs appealed to both modernists and folk art collectors, prompting the inclusion of numerous examples in major museum collections. As noted above, these artifacts were often shorn of their historical provenance, which was considered irrelevant, if not antithetical, to the folk art enterprise. The late-1930s Index of American Design, sponsored by the federal government, popularized tavern signs through remarkably detailed watercolor renderings, and the approach of the American Bicentennial in 1976 witnessed yet another upsurge of interest in historic tavern signs during the 1960s and 1970s.

Despite their low survival rate, tavern signs played a vital role in the development of art and visual culture, in Connecticut and throughout America. As the most conspicuous early form of public art, they offered ordinary people inspiring glimpses of colorful imagery, in times when book illustrations, prints, and paintings were relatively scarce. The mid-19th-century Boston portrait painter Francis Alexander vividly recalled the impact these creations had had on him, as a farm boy in Killingly, Connecticut: “I then made up my mind to become an ornamental or sign painter . . . . I thought sign painting the highest branch of painting in the world. I had been at Providence – had seen the signs there, and those were the only marvels in painting that I saw till I was twenty . . .”

Today, the visual legacy of tavern signs–particularly the distinctive shapes of early post-and-rail signs–remains firmly embedded in the American imagination and on the American landscape. This legacy persists in the obvious echoes of contemporary pub and country inn signs as well as in the shapes and imagery of a wide array of modern enterprises touting comforting, reliable services, from fuel stations to undertakers to banks.

Susan P. Schoelwer, PhD, is Curator at George Washington’s Mount Vernon, the most-visited historic home in America; she previously served as Director of Museum Collections at the Connecticut Historical Society.