By Paula Gibson Krimsky

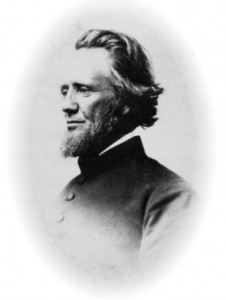

Frederick Gunn is recognized today not only as an abolitionist and educator but also as the “father of recreational camping” in the United States. In fact, for Gunn, these three passions were uniquely bound together in the school he founded in 1850. The founder’s name alone alerts the unfamiliar to the fact that The Gunnery is not a military school but an eponymous reflection of a man and his vision.

Frederick W. Gunn, ca. 1860s – The Gunnery Archive

Gunn, who had been traditionally educated and held a degree from Yale University, resisted the familiar establishment trappings of the Victorian period when he created his own school. Three pillars upheld his vision: the importance of building character, the need to abolish the institution of slavery in this country, and reverence for nature. These driving concerns melded into a core educational philosophy. Gunn not only believed that nature was an inherently wonderful teacher but that learning how to manage oneself outdoors was necessary preparation for the coming Civil War, which he predicted as the inevitable outcome of the abolition movement. To prepare his student body for such a future, Gunn led his them on long treks, in effect teaching young people how to survive on bivouac.

An Educator’s Education

Born on October 4, 1816, in Washington, Connecticut, Frederick William Gunn was the youngest of eight children. His father, a respected farmer and deputy sheriff, and his mother, a devout Christian, both died in his 10th year, leaving his oldest brother John to raise and educate the family. Young Fred grew up in Washington, a rural, farming community nestled in the foothills of the Berkshires about 15 miles south of Litchfield, which was a bustling center on the turnpike between Hartford and Albany, New York. He went to school in nearby Cornwall. Gunn entered Yale in the class of 1837 and majored in botany. New Haven, then a thriving port city on the Connecticut coast, held little allure for the student who yearned for the rolling hills and woods of his home town, some 40 miles north. Gunn, whose love of hunting and fishing would be life-long, made his own hunting bow in college, which, his students reported in The Master of the Gunnery(1887), was “a bow which none but he could fully draw.”

In 1837, he returned to Washington. Eschewing a doctor’s profession because of an unavoidable queasiness in the presence of blood and suffering, he began his career as schoolmaster in his home town in 1843. His popularity as an instructor is attested to by observations that his classrooms from 1837 to 1846 were “filled to overflowing.”

Gunn Pays Price for Endorsing the Abolition of Slavery

Despite early success, Gunn’s career path fell victim to the great national reform movement against slavery. Having been influenced by Theodore Woolsey (the Yale professor who taught him Greek), the writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thomas Carlyle, and the work of his brother John in the abolitionist movement, Frederick became an outspoken leader for the antislavery cause in Litchfield County.

As was the case across much of New England, the Congregational Church served as the center of community activity and the social arbiter of the period. In Washington, Parson Gordon Hayes, an unabashed supporter of slavery, personified that role. He justified human bondage on biblical grounds and delivered sermons condemning the abolitionists. Under the cleric’s influence, Gunn’s teaching became anathema, and parents began withdrawing students from his classroom. It is said members of the community feared social and political ostracism, but, in fact, the abolitionist movement in New England of the 1840s was unpopular and regarded as radical.

When it became nearly impossible to earn his living as a schoolmaster, Gunn received an invitation from his friend Henry Booth in nearby Roxbury to teach at an academy in Towanda, Pennsylvania—a community more tolerant of abolitionist views. During this period of exile, nature remained Gunn’s salvation. He wrote to his fiancée, Abigail I. Brinsmade, back in Washington about taking his students to lie on roof tops and teaching them to identify the constellations in the starlit sky. His classes also took spring walks to identify early flowers and bird songs. In winter, they walked the local riverbed, identifying animal tracks and hibernation caves.

Gradually, the tide of public opinion in New England changed on the question of slavery. A homesick Frederick Gunn, now married to Abigail and father to his first child, quickly accepted the urgings of family and friends to come home to Washington, where they assured him he would be welcome. The Gunns returned to Connecticut in the summer of 1849.

The Gunnery Unites Nature and Education

This time, Gunn established a school in his own vision. In 1850, he and Abigail opened the doors to their rambling Victorian home on Washington’s hilltop Green (near the Congregational Church that had ostracized him almost a decade earlier) to about a dozen students. The students boarded at the Gunns and with other families in the neighborhood. From the beginning, girls were accepted as well as boys, although, until 1854, many of the girls chose to go to Judea Seminary, a girls’ school also on the Washington Green, run by Abigail’s sister Mary Brinsmade. In 1872 the first two of four Chinese boys came to The Gunnery under the auspices of the Chinese Educational Mission, which was based in Hartford. This began a long tradition of welcoming international students to the school.

Years later, in an 1877 speech to fellow educators, Gunn emphasized the importance of nature in promoting learning for boys and girls. “The ideal school, “ he said, “ is set in the country, or, if in the city, the generous city fathers have afforded it liberal space with trees and flowers.”

Gunn’s teaching methods proved to be well-suited to the temper of the times, and the school grew and prospered. He was an early proponent of physical exercise and sport as an integral part of the curriculum. He participated enthusiastically in student games of baseball, football, and shinny (a forerunner of hockey). Fishing and hunting, too, were as much a part of the school’s routines as the reciting of Latin verbs. Gunn was known to declare a holiday from class when the weather was particularly suitable and to lead his students on tramps through the woods and along the waterways, where he drew their attention to the wonders of nature hidden under the leaves and behind the hillocks.

Civil War-Inspired Training Evolves into Camping Movement

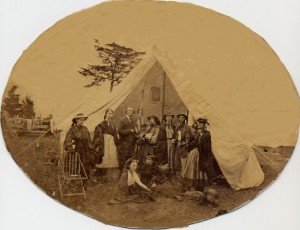

Frederick Gunn’s reputation as the founder of recreational camping emerged during the early 1860s, when he organized long marches for his students who then numbered about 30 boys and a dozen girls. In 1861, he led his first trek 30 miles from Washington to Welch’s Point at Milford, Connecticut, on Long Island Sound. The group camped there for 10 days, and amidst swimming and foraging, they performed military drills in preparation for service in the Union Army. The students called it “gypsying.”

Mr. Gunn (center) Girls’ camp, Milford, 1863 – The Gunnery Archive

Camping at Point Beautiful on Lake Waramaug, New Preston, ca. 1870s – The Gunnery Archive

The success of the Civil War era camps gave way to summer camps in the 1870s at Lake Waramaug, about seven miles north of The Gunnery. A letter, whose author and date are unknown, spoke of the preparations for the summer camp. The writer described camp tasks and activities, such as ball-games, swimming, hiking, fishing, and boating. He also wrote about the morning bugle call for the “Family Meeting” where Mr. Gunn would give advice and “cautions” for the coming day: “no swimming alone, the big boys to care for the younger ones, etc.” In the evening, they would sing “camp songs” with organ accompaniment played by Mr. Gunn.

The camps came to an end when the educational year began to change and a long school vacation in the summer replaced the winter respite. Mr. Gunn, who had turned many of his duties over to his eventual successor, continued to teach up to his death in 1881. His camping legacy was continued by his son-in-law John Brinsmade, who inherited the school, and has been supported by all subsequent headmasters.

Many of Mr. Gunn’s students formed their lives around his lessons and love of the outdoors. William Hamilton Gibson, Class of 1866, for example, became a prominent naturalist, author, and illustrator, known for his meticulous depiction of such natural phenomena as the bombardier beetle and the cross fertilization of plants by bees. Ehrick Rossiter, Class of 1870, became a renowned architect whose distinguishing characteristic was fitting his buildings into the landscape. Richard Burton, Class of 1876, became a well-known lecturer on natural wonders of the world, and A.S. Gregg Clarke, an 1870s graduate, went on to found a still-extant canoeing camp, Keewaydin, in Maine.

In 1986, the American Camping Association celebrated its 125th year by replicating the walk of Gunn and his students to Milford and holding a camp on the town’s Gulf Beach for 1,500 campers from around the world. In 2011, on the organization’s 150th anniversary, it officially recognized the organized camping movement in the United States as having begun in 1861 with Mr. Gunn’s camps in Milford. Today, The Gunnery continues to send its students on camping and hiking expeditions through the activities of its Outdoor Club and the Sophomore Saunter. It also commemorates its founder’s visionary educational philosophy with an annual all-school walk of about eight miles that takes place as close to Mr. Gunn’s October birthday as possible.

Paula Gibson Krimsky, whose great grandfather was a student of Frederick Gunn’s during this period, holds a BA in history from Smith College and is the archivist/historian at The Gunnery as well as its Associate Director of Communication.