By Emily Clark

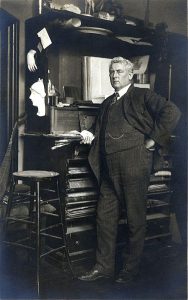

Though he was born in West Point, educated in Europe, and died in New York City, artist Julian Alden Weir called rural Connecticut home. From the serenity of his farm in Windham to his Branchville residence he called a “haven of refuge,” peaceful Connecticut locales provided Weir the inspiration to create hundreds of paintings and become one of America’s leading Impressionists.

Early Studies in New York and Paris

The 14th of Robert Weir and Susan Martha Bayard’s 16 children, this renowned American artist was born on August 30, 1852. Art surrounded Weir from a young age—his father was an art professor at the U.S. Military Academy and his older brother John was also a well-known artist. At age 17, Weir enrolled at the National Academy of Design in New York. Four years later, eager to refine his art, he moved to France to continue his education at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, learning from artists Jean-Leon Gerome and Jules Bastien-Lepage.

Originally conservative in his art, Weir soon began to veer away from traditional techniques to express his own ideas. This led to his work with Impressionism, though he was initially disgusted with this style in France, referring to such paintings as “horrible things . . . worse than the Chamber of Horrors.” When he returned to New York in the late 1870s, Weir became a teacher at the Art Students League and Cooper Union Women’s Art School, helped establish the Society of American Artists, and befriended a group of other promising young artists—including Winslow Homer.

Windham and Branchville

While teaching a drawing class in New York, Weir met Anna Dwight Baker of Windham, Connecticut, a student who soon became his wife. Just before their wedding in 1883, Weir purchased a farm in bucolic Branchville. Weir’s brother John called the sprawling homestead of over 150 acres “a pleasant place for retreat.” The pastoral farm, along with another in the charming village of Windham, provided places for Weir—and his growing family of three daughters—to relax and work, away from the hustle and bustle of New York.

Over the next 36 years, the Weirs made their home in Branchville and the artist honed his skill, inspired by the rural life surrounding him. Weir’s painting Spring Landscape, Branchville was merely the first of many. The peaceful paintings of sleeping dogs, waving grasses, and even Anna sitting quietly on the steps of their home became the trademark images of Weir’s works. After Anna’s sudden death, however, Weir sought solace elsewhere—urban Chicago—until he returned east to marry Anna’s sister Ella in 1893.

A Flourishing Career in Impressionism

At the close of the 19th century, Weir’s status as an Impressionist painter and landscape artist flourished as he experimented with pastels and etchings and learned from his American contemporaries such as Childe Hassam and John Twachtman, who often visited him in Branchville to paint the beautiful Connecticut countryside. Weir also explored the skills of Japanese artists, allowing him the opportunity to try different types of patterning, cropping, and toning.

Along with Hassam, Twachtman, and seven others, Weir formed “The Ten American Painters”—or “The Ten,” as they became commonly known—and they presented their work together throughout the coming years. Considered progressive for their time, these artists veered from the outdated styles of the National Academy of Design and Society of American Artists (with which Weir was no longer associated). During one show, an art critic described Weir as “the first among Americans to use Impressionistic methods and licenses successfully.” During a joint exhibition with Twachtman, Weir exhibited beside the famed French Impressionists Claude Monet and Paul Besnard.

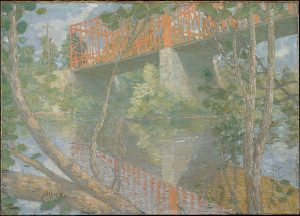

Though Weir produced more than 450 paintings, his most critically acclaimed is the 1895 masterpiece The Red Bridge—an image of an iron truss bridge high above the Shetucket River in Windham. In this painting, the reflections on the water are astonishingly realistic, thanks to Weir’s ability to unite the colors of the red bridge with the greens of the wooded backdrop and the blues of the sky and river.

Later Years and Legacy

Connecticut’s landscapes and natural environments continued to dominate Weir’s attention until his death in December 1919. His collections garnered him numerous awards and coveted positions on boards and academies, such as president of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors and member of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts in the early 1900s. Princeton and Yale bestowed honorary degrees upon him and his paintings now hang in institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington D.C., and the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford. Senior curator of American paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Erica Hirshler, once asserted that “there are several artists like Weir who have been called the fathers of the American Impressionist movement, but Weir was certainly at the heart of it.”

Today, Weir’s beloved farm in Branchville is the 60-acre Weir Farm National Historic Site—the only park unit devoted to American painting and where the artist spent his last days, comforted by the natural beauty of his longtime home. “Really, I know not what I am best at,” he once wrote. “I believe I am a fisherman, dreamer and a lover of nature . . . and if I lived to 120 I might become an artist.”

Emily Clark is a freelance writer and an English and Journalism teacher at Amity Regional High School in Woodbridge.