By Sandra Whitney

Early Years

Alfred Howe Terry was born on November 10, 1827, to Alfred Terry Sr. and Clarissa Howe Terry. Terry had three brothers and five sisters and remained close to his family throughout his life, especially to his brother Adrian and his sisters. As described in a letter written by a cousin, Rose Terry Cook, “We were children together and in the somewhat turbulent crowd of cousins—for the Terrys are a hot-tempered race—Alfred was always calm, kindly and generous. If we had a quarrel or some wrong was done among us, our grandfather always said after hearing the eager and contradictory statements of the others, ‘send for Alfred; he will tell me the exact truth, whether for or against him.’”

In 1829, the Terry family moved to New Haven where Alfred Terry Sr. entered the book and stationary business. Terry attended local schools and entered Yale Law School in 1848. He left Yale without graduating and began the practice of law in 1849 after a brief apprenticeship in a law office. In 1849, Terry was admitted to the Connecticut bar. In 1850, he became city clerk. He held this job for four years until he was appointed clerk of the Superior Court of New Haven. During this time, Terry followed his interest in military science. He joined the local militia in 1849 as a private and by 1860 advanced to the rank of colonel. He spent the summer of 1860 in Europe traveling and studying military fortification, ships of war, and any other military materials available for perusal.

The Civil War Years

Glass negative of General Alfred Howe Terry, ca. 1860–75 – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Brady-Handy Photograph Collection

Terry returned to Connecticut in 1861 in time to respond to President Lincoln’s urgent call for volunteers. Terry enlisted for a three-month period and became Colonel of the 21st Regiment of the Second Connecticut Volunteers. On May 7, 1861, he moved with his men to the Washington area to defend the nation’s capital. In July of 1861, he participated in the First Battle of Bull Run. Terry returned to Connecticut at the end of his 90-day enlistment.

Terry then re-enlisted for three years and became commander of the 7th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry with Joseph R. Hawley as Lieutenant Colonel. The 7th consisted of 1,018 men and was mustered into service on September 7, 1861. The regiment was ordered south and became part of the expedition against southern coastal points commanded by Major General T. W. Sherman and Admiral DuPont. In 1862, Terry took part in the battle of Port Royale, South Carolina, in which the 7th was the first to land and raise the Union flag on the soil of South Carolina. On January 13, 1862, Terry took part in the siege and final surrender of Fort Pulaski. The 7th was given the honor of being the first to garrison the surrendered fort.

Terry was promoted to Brigadier General of Volunteers in May of 1862. He was assigned command of the 1st Brigade of General Brenham’s division where he fought on James and Morris Island and took part in the battles of Fort Wagner and Fort Gregg. It was at this time that Terry and Colonel Hawley were sent on special business to New York City and Washington to secure Spencer rifles for his regiment and to meet with President Lincoln and General Terry for war instructions. In the summer of 1863, Terry took a leave of absence after contracting malaria. Upon his return to active duty, Terry took command of the 10th Army Corp of the Army of the James under General Benjamin Butler.

Hero of Fort Fisher

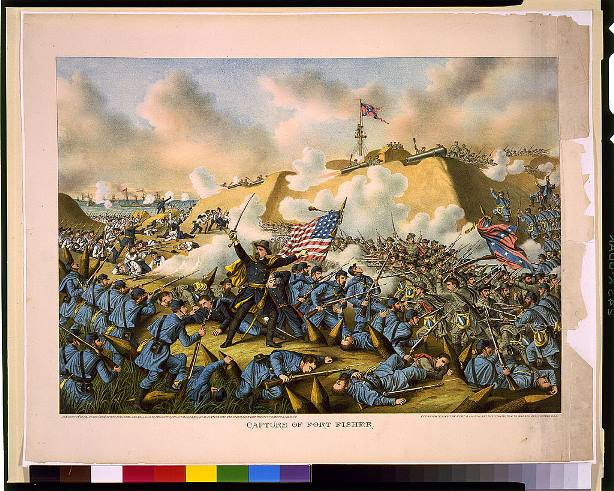

In December of 1864, General Butler attempted to capture Fort Fisher, one of the last strategic forts of the Confederacy. There was no joint planning with Rear Admiral David Porter, however, and the lack of coordination spelled defeat for the Union forces. General Ulysses Grant requested the removal of Butler and put Terry in charge. Terry focused on capturing Fort Fisher. He landed his men without difficulties and set up a defensive line and advanced his troops. The navy laid down a barrage of fire in front of the soldiers’ line as they moved forward. As the soldiers gained ground, the fire from the navy moved with them, keeping well ahead of Terry’s men. Cooperation between the army and the navy proved very effective. Fort Fisher fell on January 16, 1865.

Terry received national recognition for his service in capturing Fort Fisher. Secretary of War Edwin W. Stanton wrote the following to Terry: “The Secretary of War, in the name of the President, congratulates you and the gallant officers and soldiers, and tenders you thanks for the valor and skill displayed in your part of the great achievements in the operations against Fort Fisher and in its assault and capture. The combined operations of the squadron under command of Rear-Admiral Porter and your forces deserve and will receive the thanks of the nation and will be held in admiration throughout the world as a proof of the naval and military prowess of the Unites States.” Terry was promoted to the rank of brigadier general of the regular army and major general of volunteers. On January 26, 1865, General Terry was given the formal thanks of the nation in a resolution passed by Congress.

Kurz & Allison, Capture of Fort Fisher, 1890, chromolithograph – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Post-Civil War

United States Army officer’s dress chapeau bras owned by General Alfred Howe Terry, 1872 – Connecticut Historical Society

After the Civil War, Terry returned to New Haven and thought about resuming his law practice, but made the decision to remain in the army when General Stanton offered him the command of the Department of Virginia. From June 1865 to August 1866 Terry remained on duty in the South. His next command was in the northern plains (from 1866 to 1869) as commander of the Dakotas. He returned back east in 1869 as Commander of the South, where he remained for the next three years and four months. His main concern was to maintain law and order in an area rampant with election fraud, riots, yellow fever epidemics, violence committed on federal internal revenue collectors, and a variety of other crimes, including murder. The primary disruption of law and order came from members of the Ku Klux Klan and other similar organizations that promoted white supremacy. Terry soon saw that it was necessary to use military power to keep the peace and wrote a legal document reinstating the process of military control so that “life and property may be protected, freedom of speech and political action secured and the rights and liberties of freeman maintained.” The army gradually withdrew from the region as the southern states rejoined the Union and military control was phased out. The end of Terry’s Reconstruction duties opened the door for his return to the Dakotas and his work with the Sioux.

Terry took command of the Dakotas and looked forward to this duty as he anticipated accomplishing significant and lasting work among the whites and Native Americans of the northern plains. The four main challenges facing Terry in his new assignment were to organize the new department, protect the settlers of the region, provide safe routes to Montana, and obtain peace with the Sioux. During his first tour of duty in the Dakotas, Terry participated in the Peace Commission of 1868 which led to the signing of the Treaty of 1868 with the Sioux. This treaty ceased to recognize Native American tribes as independent nations and, as a step towards possible U.S. citizenship, held each Native American accountable to the laws of the country. In addition, the military was to return hostile Native Americans to their reservations and not allow them to roam and hunt. The government also transferred the handling of Native American affairs from the Department of the Interior to the War Department. Various Sioux tribes signed this treaty but few were convinced that peace on the plains would last.

Terry’s last assignment was as commander of the Division of the Missouri from 1886–1888. He was promoted to major general of the regular army on March 3, 1886, thus becoming the only non-West Point graduate among the Civil War officers to attain that rank. His health began to decline, however, and he retired in 1888 due to illness. He died in New Haven, Connecticut, on December 16, 1890, and is buried in Grove Street cemetery. Terry’s memorial tablet on his gravestone reflects some of the words so often spoken about him during his lifetime:

IN MEMORY OF

ALFRED HOWE TERRY

MAJOR GENERAL, U.S.A

HONORED BY HIS COUNTRYMEN FOR

HIS UNSULLIED PATRIOTISM. AND FOR HIS

DEVOTED SERVICE TO THE NATION IN

WAR AND IN PEACE. LOVED FOR THE PURITY

OF HIS LIFE, AND THE NOBILITY OF HIS CHARACTER

Sandra Whitney is a graduate student in public history at Central Connecticut State University and is employed full time at the Otis Elevator Company.

This article was published as part of a semester-long graduate student project at Central Connecticut State University that examined Civil War monuments and their histories in and around the State Capitol in Hartford, Connecticut.

<< Previous – Home – Next >>