By Steve Grant

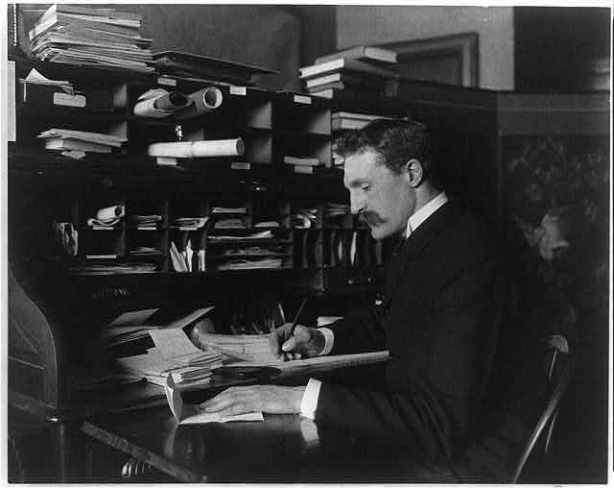

Gifford Pinchot was a pivotal and enormously influential figure in the conservation movement that emerged in the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Simsbury in 1865 and educated at Yale University in New Haven, Pinchot was the first chief of the US Forest Service, a founder of the Yale School of Forestry, a long-time confidante of President Theodore Roosevelt, a governor of Pennsylvania, and founder of the Society of American Foresters.

He was a Republican who often espoused a progressive philosophy, sometimes even pursuing what was for the time a radical philosophy. Pinchot, notably, fought for increased regulation of timber companies and electric utilities.

Early Training Influenced National Policy

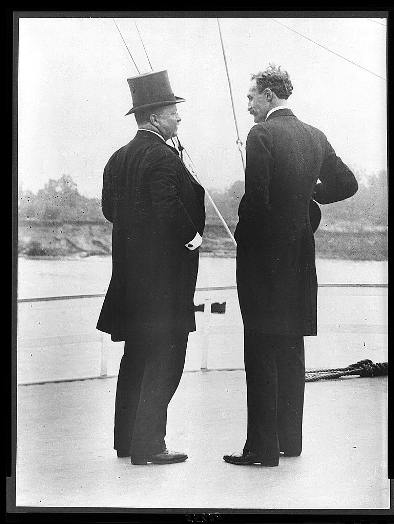

President Theodore Roosevelt and Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot. The picture was taken on the trip of the Inland Waterways Commission down the Mississippi River in October 1907 – Library Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

As a young man, at the urging of his father, Pinchot embraced science-based professional forestry, a discipline then emerging in Europe, where he traveled for post-graduate study. Returning home, he was instrumental in introducing modern forestry in the United States; he began his career as the private forester at George Vanderbilt’s Biltmore Estate in North Carolina, effectively putting forest management into practice in America.

In 1900, Pinchot and a good friend from his Yale undergraduate years, Henry S. Graves, established the Yale School of Forestry, with Graves serving as its first dean. Because professional forestry was still in its infancy, Pinchot and Graves saw the school as a way to produce a new wave of foresters trained in the latest forest management science and methods. (Today, the school is called the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.)

As a close advisor to Teddy Roosevelt, Pinchot was instrumental in many of the path-breaking conservation programs that emerged during the Rough Rider presidency. Most notably, he oversaw an enormous increase in the amount of national forest land holdings, a feat accompanied by greatly improved organization and management within his agency. In 1905, when Pinchot became chief of the US Forest Service, there were 60 federal forest reserve units, as they were then known, totaling 56 million acres. In 1910, when he left the service, there were 150 national forests totaling 172 million acres.

Nationally, Pinchot’s reputation today rests largely on his contributions to a national conservation ethic. Conservation, he wrote, should yield “the greatest good, for the greatest number, for the longest run.”

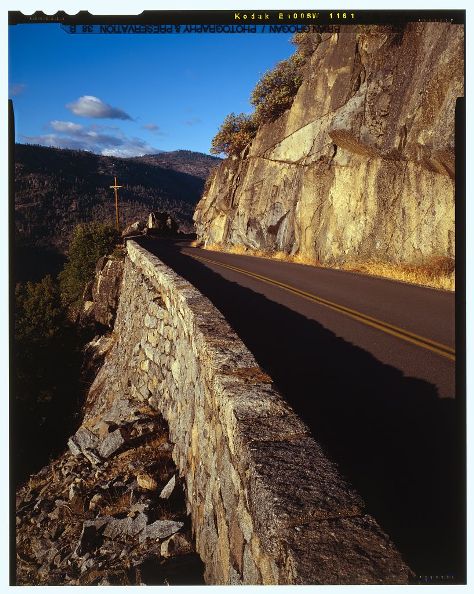

Pinchot is faulted by some as too pragmatic, too willing to compromise on conservation issues, perhaps because of his famous battle with John Muir over the need for a dam in California’s Hetch Hetchy Valley, within Yosemite National Park. Pinchot said the reservoir the dam would create was essential if San Francisco was to have an adequate water supply. Muir, founder of the Sierra Club, speaking for those who would preserve vast stands of wilderness, said it would be unconscionable to dam the spectacularly beautiful Hetch Hetchy valley.

A Practical Environmentalist

View of Hetch Hetchy Dam, Tuolumne County, CA – Library Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Historic American Buildings Survey

Pinchot can be seen as a proponent of a practical environmentalism in which natural resources are used for the good of society—but only if done so on a sustainable basis ensuring the resource is available in perpetuity. This was almost heresy in his time, when the finite nature of resources, whether forests or mineral, was all but ignored.

To consider the nation’s resources inexhaustible, as many did in those years, was “stupidly false,” Pinchot said. “The conservation of natural resources is the basis, and the only permanent basis, of national success,” he wrote in his 1910 book The Fight for Conservation.

When US Interior Secretary Richard Ballinger sought to turn some publicly held Alaskan coal lands to private ownership, Pinchot was outraged and began a bureaucratic battle within the administration that ended when President William Howard Taft, Roosevelt’s successor, fired him. Taft was widely criticized for firing Pinchot, and Pinchot welcomed the attention, believing it brought focus to national conservation issues.

Pinchot was an environmentally sensitive forester who, working in public service, pushed the conservation agenda as aggressively as he could while still getting things done, sometimes even pushing for change that proved too radical for the times. For example, Pinchot argued for the regulation of forests, even private forests, all but unheard of in his day. People in Alaska, enraged at his policies, burned an effigy of Pinchot and complained that “he thinks more of trees than people.”

Pinchot was deeply involved in Roosevelt’s unsuccessful presidential campaign in 1912 as the candidate of the Progressive Party, nicknamed the Bull Moose Party because, when Roosevelt was asked if he was “fit” to be president, he answered that he was “fit as a bull moose.”

After his forest service years, Pinchot served two terms as a governor of Pennsylvania, pursuing a progressive agenda of social and environmental goals. He ran for the US Senate from Pennsylvania three times, without success.

Pinchot’s wife, Cornelia Bryce Pinchot, whom he married in 1914, was a wealthy woman interested in such progressive causes as birth control, the vote for women, and civil rights. She was long active in liberal causes and ran several times, unsuccessfully, for political office. When African American contralto Marian Anderson made her famous performance at the Lincoln Memorial on Easter day in 1939, Cornelia and Gifford Pinchot were her hosts in Washington, DC. The Pinchots had a son, Gifford Bryce Pinchot.

Pinchot’s Legacy and the Yale School

Pinchot died of leukemia in New York in 1946 at the age of 81, but his legacy continues to influence policy. The Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies has for a century been in the forefront of forestry and environmental research. Today it attracts graduate students from throughout the world, and its research is increasingly global in reach.

Other testaments to Pinchot’s vision are the Pinchot Institute for Conservation and the Grey Towers National Historic Site (formerly the Pinchot’s Pennsylvania estate). First proposed by Pinchot’s son Gifford, the Pinchot Institute is a nonprofit organization that works to encourage sustainable forestry.

The Columbia National Forest, originally part of Washington State’s Mount Rainier Forest Reserve of 1897, was renamed the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in his honor in 1949. The Pinchot Forest now totals more than 1.3 million acres and includes the Mount Saint Helens National Volcanic Monument. Pinchot Pass in Kings Canyon National Park in California and Gifford Pinchot State Park in Lewisberry, Pennsylvania, also honor him.

In Simsbury, beside the Farmington River, grows the largest known tree in Connecticut and one of the two or three largest American sycamore trees in the US. It is dedicated to the memory of native son Pinchot.

Steve Grant is a longtime Connecticut journalist specializing in natural science, environmental, and outdoor recreation topics.