By William N. Peterson for Connecticut Explored

“Back! Back on the Albatross!” shouted an anxious Admiral David G. Farragut. His powerful flagship, the steam frigate USS Hartford, was hard aground on a Mississippi River mud-bank 150 river miles south of Vicksburg, the Confederate “Gibraltar.” The much smaller steam gunboat Albatross was securely tied to its port side, and both were under severe enemy cannon fire emanating from the forts at Port Hudson, Louisiana, a strong Confederate bastion. It was 1863, and, after capturing New Orleans and Baton Rouge, the victorious admiral’s fleet was now attempting a risky nighttime passage of the formidable fortifications at Port Hudson in an effort to join forces with General Ulysses S. Grant, who was then approaching Vicksburg from the north.

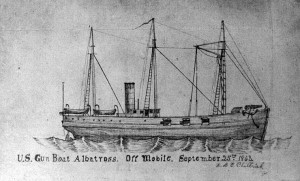

The 445-ton Albatross was built three years before the war in Mystic, Connecticut, at the shipyard of George Greenman and Company. Before the war she ran regularly, carrying both cargo and passengers, between Providence and New York. But the navy needed ships—any ships—at the start of the war, so the government purchased the heavy-timbered Albatross and quickly converted it into a gunboat. By 1863 the Albatross had distinguished itself as a blockader as part of Farragut’s Mississippi River squadron.

Sketch of the USS Albatross off Mobile, Alabama, September 25, 1863. The Private Papers of William M.C. Philbrick – US Naval Historical Center

For the daring passage up the river, Farragut had decided to lash the smaller gunboats in his fleet to his larger vessels to help protect the smaller ships from the heavy guns on the bluffs. He chose the nimble Albatross as consort for his flagship. Now, the night sky ablaze with muzzle flashes from friend and foe and the pitch pine bonfires lit along the opposite shore by Confederates in an attempt to light up the Union fleet, the engagement was deadly, noisy, and nerve shattering. The little Albatross suffered the effects of the very first shell fired by the Confederates, which exploded with a reverberating blast over its deck.

In the lead of the seven-ship flotilla, Hartford had run aground and become the target of the rebel effort to thwart his fleet’s passage. Farragut quickly ordered her engines full ahead and the Albatross’s engines full aback to dislodge the flagship. It worked, and both vessels, now free of the mud, steamed safely above the belching fortress. Admiral Farragut was effusive in his praise of the staunchly built Albatross and its crew for saving his ship. When Albatross later needed to be sent for refitting, he wrote the navy department that “she is one of the finest blockaders in the squadron. I beg the department will not remove it from my squadron.”

Lincoln Names a Connectican to Lead the Union Navy

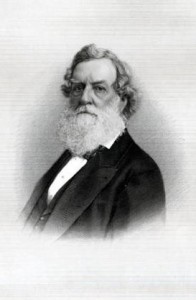

USS Albatross was just one of scores of Connecticut-built vessels that saw service in the Civil War. She had been among the early purchases by Abraham Lincoln’s newly appointed Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. With his white bushy beard and ill-fitting wig, Glastonbury, Connecticut’s Gideon cut an unusual figure. He had never served in the navy, but his organizational skills and family background in shipbuilding soon earned him the nickname “our Neptune” from President Lincoln.

At the start of the Civil War, the navy was in disarray, with much of its officer corps harboring Confederate sympathies and its ships scattered around the globe. Only a handful of vessels were available to establish the initial Union blockade of Southern ports. Within months, Welles, with the aid of his extraordinary Assistant Secretary Gustavus Fox, brought order out of chaos. He initiated a major shipbuilding program and began acquiring, through purchase and lease, scores of merchant vessels of all types. By the war’s end, the United States Navy was second only to that of Great Britain in size and included innovative ironclads, spar-torpedo boats, and even submarines.

Perhaps due to Welles’s influence, a surprising number of the navy’s fleet came from Connecticut, where they proved invaluable. Some were assigned to combat and blockade duty, and others served in vital transport services. Welles was astute and successful, and when he left office in 1869 he became the longest-serving secretary of the navy in US history.

Before the war, Connecticut shipbuilders had been active building cotton carriers from Southern ports. The Civil War brought about the collapse of the Southern cotton trade and, with it, the demand for cotton carriers. Connecticut’s shipbuilders were quick to capitalize on and adapt to new government demands for steam transports and gunboats essential to the war effort.

Mystic-built Ships

Before the war, Mystic, with a population of just 2,500, was famous for building fast clipper ships and other sailing vessels but quickly converted to building steamships once war broke out. In fact, in response to war demands, more steam vessels were built at Mystic between 1861 and 1865 than at any other New England port. “All our shipyards are hard at work. Whatever the effect of the war in other places, we believe it will prove a benefit to Mystic,” wrote the editor of the Mystic Pioneer newspaper on May 18, 1861. And, so it was. Mystic shipyards launched 56 steamers during the war, representing 5% of Northern steamship construction.

Mystic-built vessels participated in nearly every theater of operation during the conflict. The ironclad USS Galena launched by Maxson, Fish and Company in 1862 led a valiant, if spectacularly unsuccessful, dash up the James River, Virginia, in concert with General George B. McClellan’s ill-starred Peninsula Campaign. This back-door attempt to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond by water was halted by extensive Confederate fortifications at a bend in the river and the imposing Fort Darling high above on Drewry’s Bluff. The Confederates had also placed substantial obstructions at the river’s bend. In the lead, the lightly armored Galena was devastatingly pierced by plunging cannon fire, eliciting her captain’s later, wry report, “we proved she was not shot proof.” The poorly positioned Galena survived a withering 52 hits and could go no further in battle; she was, however, able to steam out of range of fire on her own power.

Effect of Confederate shot on the USS Galena, 1862

– Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Largely sponsored by Cornelius Bushnell of Madison, Connecticut, Galena was one of the three original ironclads, including the New York-built USS Monitor with its revolutionary thick iron plating and innovative revolving turret, ordered by the navy and built to different specifications. Galena was more conventional in design, with sloping iron-plated sides. She was also dubbed the first “ocean going” ironclad in the United States Navy. Following her hammering at Drewry’s Bluff, Galena’s armor was removed, and she was converted into a wooden gunboat and served through the war including participating in the Battle of Mobile Bay.

The Charles Mallory and Sons-built screw steamer Varuna, a converted merchant vessel named for the Hindu god of the sea, was launched in 1861. Varuna was in the first division of Admiral Farragut’s fleet during the campaign to capture New Orleans in April 1862. Because of her speed she lurched to the head of the attacking column, where she received inordinate attention from Confederate gunners at forts Jackson and St. Phillip and the rebel fleet trying to block the way to the South’s largest city. Varuna is credited with sinking three Confederate ships and damaging another before being fatally rammed. During this close-quartered fight she was surrounded by Confederate vessels, and her bow-mounted parrot rifle was canted awkwardly downward so she could actually fire through her own bow at one of her antagonists. One participant said, “it was like the breaking up of a thousand worlds. Crash-tear-whiz! a hailstorm of iron perfectly indescribable.” Although Varuna had the unhappy distinction of being the only Union vessel sunk during the fiery passage, she nonetheless bubbled to the muddy bottom of the Mississippi with her US flag flying defiantly and firing a final salvo at the enemy. It was a fierce engagement that inspired a contemporaneously famous poem called, appropriately enough, “The Varuna.”

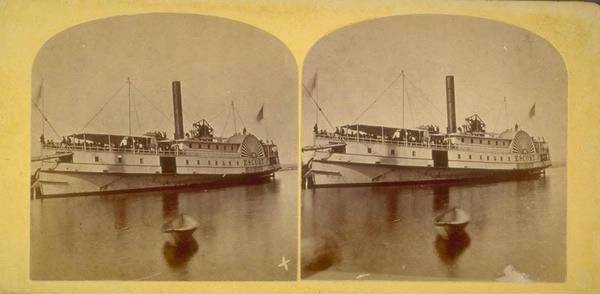

The Greenman-built side-wheel steamer Escort with a regiment of black soldiers and tons of supplies aboard relieved a besieged Union garrison at Plymouth, North Carolina, by running a gauntlet of cannon and rifle fire on the Tar River in 1864. That same year the Mallory-built steamer Thames New London, another Greenman product built before the war, captured eight Confederate blockade runners in the Gulf of Mexico, a feat made possible by her speed and shallow draft. She was so successful during the early blockading period that the rebels referred to her as “that insolent Lincoln cruiser.” New London later saw considerable action on the Mississippi.

Sidewheel steamer Escort built by George Greenman & Co., 1862, Mystic – Mystic Seaport and Connecticut History Illustrated

Although Mystic led the way in Connecticut shipbuilding, many other shipyards in the state added to the sometimes-frenetic production. Shipyards at Fair Haven, East Haddam, Portland, and Norwich together built more than 30 vessels that were used in various ways during the war.

Engines and Boilers, Too

Many of the engines, boilers, and other machinery for the navy’s ships were also manufactured in Connecticut. The Mystic Irons Works and Reliance Machine Company in Mystic were particularly active in this regard, as were Albertson and Douglas in New London, the Thames Iron Works in Norwich, the Pacific Iron Works in Bridgeport, and Woodruff and Beach in Hartford, which built the engines for USS Kearsarge, the ship that ultimately destroyed the most famous Confederate commerce raider the CSS Alabama. Related industries prospered at New London making war goods for the navy. The Wilson Manufacturing Company, for instance, turned out thousands of boarding pikes and copper wheels for naval gun carriages. The C. D. Boss Company specialized in baking ship biscuits, while its owner Charles D. Boss also served for a time as navy paymaster in New London.

Connecticut Ships on the Confederate Side

Interestingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, a few Connecticut vessels found themselves in service to Confederate forces. The side-wheel steamer Victoria was launched by George Greenman and Company in 1859 for use as a towboat on the Mississippi River. When war broke out she evidently was commandeered for use as a blockade runner and later as a gunboat by the Confederates. It is unclear from the record, but Victoria may have been captured by Union forces during the naval engagement at Island No.10 in 1862. The bark Lapwing, also built in Mystic in 1859, was captured in 1863 by the fabled Confederate raider CSS Florida. Because of her sailing speed she was armed and converted for a time into a rebel raider but was soon burned at sea to avoid recapture. Florida’s captain John Newland Maffitt had been born in Connecticut to Irish immigrant parents in 1819 but grew up in North Carolina.

Non-combatant Casualties and The Stone Fleet

A number of Connecticut-owned ships were simply casualties of Confederate commerce raiding. Perhaps most famous was the Mystic-built clipper-ship Harvey Birch, which was captured and burned in 1861 when returning to New York from Liverpool by the Confederate steamer Nashville. This early in the war destruction of a high profile commercial ship led to widespread panic in American shipping circles. The ship B. F. Hoxie and the barks Tycoon and Texana met with similar fates. The ship S. Gildersleeve, once the pride of the Gildersleeve shipyard in Portland, was sunk by the CSS Alabama. Two Noank schooners, L. A. Macomber and North America, were also victims of Confederate raiding, as were several other commercial vessels with Connecticut ties. A number of other New London-based whalers were captured and burned in the Pacific by the CSS Shenandoah late in the war.

In 1861 the navy came up with the idea of blocking the seaborne entrances to Charleston, South Carolina, and other Southern ports by filling old ships with stone and then deliberately sinking them at the harbors’ entrances. Nine old whaling ships from Connecticut, including seven from New London and two from Mystic, were purchased for this purpose, along with 16 others from around New England. These ships became known as “the stone fleet.” The effort proved futile, as the ocean currents entering and ebbing in the targeted harbors soon swept away most of these sunken ships. In fact, this ill-conceived plan actually helped to deepen the harbor channels at Charleston.

Connecticut’s Sailors and Commanders

As Connecticut’s largest deep-water port New London was the center of navy recruiting throughout the war. “Those who wish to be enrolled among the gallant heroes of the American Navy should not let this opportunity pass,” read a New London Daily Chronicle advertisement in 1862. The frigate USS Sabine spent a good deal of time at New London serving as the port guard ship and in recruiting.

In addition to Welles and Bushnell, a few other Connecticut people stand out for their naval or maritime contributions to the war effort. New Haven-born Commodore Andrew Hull Foote led the naval forces that, in conjunction with General Grant’s land forces, provided some of the earliest Union successes in the war when they captured forts Henry and Donelson on the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers in Tennessee early in 1862. The capitulation of Fort Henry in particular was almost wholly the result of Foote’s gunboat bombardment. His flotilla later captured Island No. 10 on the Mississippi, and he went on to be promoted Rear Admiral in charge of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron.

Joseph Lanman from Norwich was commodore of the Pacific Squadron early in the war and later led part of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron and a naval division during the bombardment and capture of Fort Fisher, a strong bastion that protected the seaborne entrance to Wilmington, North Carolina. This action closed this last major Confederate port on the Atlantic coast. Lanman was later promoted to Rear Admiral.

Rear Admiral Francis Hoyt Gregory of Norwalk was retired at the time of the war but was brought back to superintend naval construction in various commercial shipyards. Other men from Connecticut, because of their shipbuilding expertise, such as Mason Crary Hill and John Forsyth from Mystic were recruited to be inspectors and “constructors” for the navy.

The story of the various volunteer regiments from Connecticut has justly received attention from historians over the years, but the contributions of the state’s ships, sailors, and shipbuilders have been largely overlooked. Nonetheless, Connecticut’s maritime and naval accomplishments contributed in many important ways to the ultimate success of Union forces during the American Civil War.

William Peterson, curator emeritus of Mystic Seaport, served as co-guest editor of the Spring 2009 “Maritime Connecticut” issue and is currently an independent historian and consultant researching Connecticut shipbuilding.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 9/ No. 2, SPRING 2011.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.