By Nancy Finlay

While the Middle East is thousands of miles from New England, the Armenian genocide during the early 20th century had a profound impact on Armenian communities in Connecticut. Numerous Armenian immigrants to Connecticut escaped the oppression and violence in their homelands. Today, descendant communities still commemorate their struggles.

The Armenian Genocide

Charles Zartarian arrival announcement in the Hartford Courant, February 26, 1922 – Connecticut State Library

On April 24, 1915, the Ottoman government arrested and deported approximately 250 Armenian intellectuals and leaders in Constantinople (today Istanbul). This marked the beginning of what has become known as the Armenian genocide. As a Christian people living in an Islamic state, Armenians had long been a significant minority within the Ottoman Empire and oppression and violence against Armenians rose for decades. With the outbreak of World War I, Ottoman authorities viewed the Armenians as an increasing threat to their security. They rounded up Armenian families and handed their homes and businesses over to Muslims.

The Ottomans systematically executed many Armenian men, while many women and children perished on their way to relocation camps during harsh marches through rugged terrain, often without food or water. It was not uncommon for those who reached the camps to subsequently die of starvation or disease. In addition, Ottomans raped, enslaved, and forced large numbers of Armenian women to convert to Islam. They sold children to childless Turks and Arabs, who also forced them to convert. Sometimes, Armenian parents sold their own children to save their lives.

While there is no precise number, an estimated 664,000 to 1.2 million people perished in the Armenian genocide. Although the Turkish government continues to deny that the genocide took place, the documentary evidence is overwhelming, corroborated by the harrowing stories of survivors. Many of these survivors wound up in Connecticut.

Survivors in Connecticut: A Few of Their Stories

Survivors of the Armenian genocide grew families and communities in various places around Connecticut. They left behind evidence of their stories in books, interviews, newspapers, the memories of their descendants, and more.

Maritza Deroian Bogosian was born in the village of Hussenig in Armenia in 1905, the oldest of five children. The Ottomans massacred her entire family in 1915. A Turkish family rescued her and took her to an orphanage. An uncle then brought Bogosian to Hartford in 1919. In 1924, she married and moved to New Britain, where she lived until her death at the age of 101 in 2006.

Elizabeth Der Hoosigian was born in Providence, Rhode Island in 1908. Her family returned to Turkey when she was an infant and all died except for Der Hoosigian and her brother who ended up in an orphanage. Elizabeth eventually returned to the United States and married Paul Yagoobian of New Britain.

Elizabeth Yegsa Aharonian was born in 1912. When she was an infant, her father left the Ottoman Empire for the United States, leaving Yegsa and her mother behind. They wound up on a death march, but before she died, Yegsa’s mother gave her to an Arab family, who cared for her until another Armenian from her village found her and brought her to an orphanage. Yegsa was 16 years old when she came to the United States and reunited with her father. In 1933, she married Nighos Mazadoorian—also a genocide survivor—and the couple settled in New Britain.

The Hartford Courant tells the story of Kidranouhi (possibly Dikranouhi) Krikorian, who in 1915 at the age of 11, saw Turks kill her mother, father, sisters, and brothers. Krikorian alone survived but an “Arab brigand” enslaved her for several years. She escaped, dressed as a boy, and joined the Armenian army. Nicknamed the “Holy Terror,” the Courant reported that she killed 75 Turks and engaged in hand-to-hand combat. In 1921, she arrived in the United States, where she hoped to join family in Connecticut.

While most survivors were women or children, some men and boys did manage to escape. The Ottomans rounded up Charles Zartarian and his mother, father, and sisters, with other Armenians and marched them to a nearby village. The family paid a Kurd to hide them from the Turks. Zartarian’s mother and sisters died, but he and his father managed to escape to Russia—Zartarian lost three fingers to frostbite and was shot in the heel along the way. Eventually, using an Armenian newspaper, they connected with an Armenian family living in Hartford who helped them get to America. Zartarian was 11 years old when he arrived in Hartford. His story was printed in the Courant and he went on to attend Harvard Law School to become an immigration lawyer.

Connecticut’s Aid to Victims

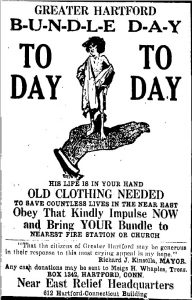

Near East Relief coordinated Connecticut’s efforts to aid victims of the genocide; its state headquarters were located in the Strand Theater building on Main Street in Hartford. Originally established to aid the Armenians, Near East Relief eventually expanded its efforts to assist all those affected by the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, including Kurds, Greeks, Syrians, and Iranians.

Although the United States did not officially recognize the Armenian genocide until 2021, Connecticut governors and legislators issued a series of proclamations and resolutions condemning the massacres that took place from 1915 to 1923. Connecticut’s Armenians continue to observe Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day each year in memory of those who lost their lives during the genocide.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.