By Holly V. Izard

Farms of the past were agricultural complexes: a house, a barn or two, perhaps an outbuilding such as a corn crib or detached woodshed, and maybe a shop for winter artisanal production. Today it is easy to admire a restored farm house without its occupational trappings, but for it to have functioned as the core of a farming operation it would have had at least one barn.

The architectural form colonists brought to the New World is called the English barn. These structures typically featured three bays—three framed sections, each defined by vertical timbers. (In post-and-beam construction, heavy framing timbers are joined and pinned together and then braced, forming the equivalent of a very sturdy box.) The center bay served as the drive, the place where carts of hay were brought in to unload and where farmers threshed grains and husked feed corn. The end bays were called “mows” and were used for grain storage and housing for livestock. In England, both mows were for grains as livestock was kept outside, but the cold New England climate led to storing grains in one mow and sheltering livestock in the other.

Another floor, inserted at the plates or roof level, supplied a second area for grain storage. This, too, was a new world adaptation of the old world form, a means to replace lost ground-level grain storage. The door for the center or “middle bay” drive was located on the eve side of the barn (the part that slants down like a house roof). Some structures also featured a corresponding door on the opposite side of the barn. English barns were finite in capacity; they could not be easily expanded for use as access was restricted to the center drive.

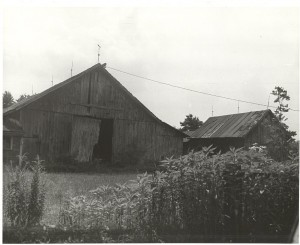

New England barn, Thompson – Historic Barns of Connecticut

The English barn prevailed in the 17th and 18th centuries, but around the time of the American Revolution, New England barns came into use and they soon predominated. In this barn form, the drive ran from gable to gable (peak to peak) with stanchions on one side and hay storage on the other. In its most advanced form, a New England barn was bi-level, with stanchions several feet below grade level on both sides and expanded feed storage above. New England barns were easily expanded by simply framing another bay at a gable end. It was a form well suited to agricultural potential in Connecticut where land, in comparison to England, was abundant. Less common in the state were bank barns, bi-level structures built into hillsides. This provided ground level access to both the upper and lower floors.

By the 20th century, barn framing technology changed and the massive hand-hewn timbers gave way to factory-milled stick framing, concrete, cinder blocks, metals, and even pre-fabricated structures. The University of Connecticut’s Cattle Resource Unit, a greenhouse-type dairy cow barn completed in 1999, has sides that roll up in warm weather for creature comfort!

The signature element of Connecticut River Valley agriculture from Connecticut to New Hampshire is the tobacco barn. These distinctive long and narrow structures feature side planks that open to allow air to flow through and dry the leaves. Built for the sole purpose of curing tobacco, these barns are particularly challenging to adapt for other uses.

Tobacco barn, East Granby – Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries and

Overall there are probably no 17th-century barns still standing in Connecticut (or anywhere else) and relatively few barns that date to the 18th-century. Most barns still on the Northeast landscape are New England-style barns from the 19th century and later. Sadly, barns are fast disappearing, victims of neglect when a property goes out of agriculture and stands in the way of residential development. In fact, the rapid demise of barns spurred the National Trust for Historic Preservation to sponsor a nationwide barn survey. Since 2004, the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation has been actively working to document barns in the state, supporting town-by-town documentation projects.

Holly V. Izard, who holds a PhD in American and New England Studies from Boston University, has written and published extensively on pre-1850 New England agriculture and social history and is curator of collections at Worcester Historical Museum in Worcester, Massachusetts.