By Bob Wyss for Connecticut Explored

Spreading its leafy limbs before the former Mansfield Town Hall is a tree of a non-native species that once covered many of the hills and valleys of Connecticut—a black mulberry. And almost directly across Storrs Road on Route 195 bordering the Altnaveigh Inn stands a second, a white mulberry.

Two hundred years ago tens of thousands of cultivated mulberry trees dotted the Connecticut landscape. Few have survived the ravages of time, the harsh Connecticut climate, blight, and the foibles of mankind. Those that remain are relics of a strange chapter in Connecticut’s history, one that featured a fabled fabric, get-rich-quick dreams spun by promoters, hucksters, and swindlers, and, finally, panic and ruin. It is the story of a burgeoning but short-lived cottage industry that was unique in the young, 19th-century American nation.

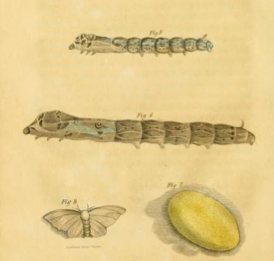

The story begins with the mulberry tree and the silkworm, which is a type of caterpillar. The silkworm prefers a diet of mulberry leaves. It produces a cocoon which, when unraveled, can be spun into silk thread. The process of silk production is called sericulture, and 200 years ago Connecticut, especially Windham and Tolland Counties, was the epicenter of US raw-silk production.

Silk worms from A Manual Containing Information Respecting the Growth of the Mulberry Tree by J.H. Cobb, 1833

Early Experiments in US Silk Production

The Chinese discovered the secrets of mulberry leaves, silkworms, and silk production 4,000 years ago and threatened death to anyone who revealed those secrets. These new threads, which had a greater tensile strength than metal cable, could be spun into a luxurious fabric that was so desired that it opened up trade across half the globe on the famous Silk Road. Eventually the secrets of sericulture spread throughout Asia and Europe.

Silkworms were first imported to Virginia as early as 1613, but efforts to build businesses around them in American colonies such as Georgia, South Carolina, and Pennsylvania were only marginally successful. In 1734 the Connecticut Colonial Assembly passed legislation offering financial incentives for silk growers. Two individuals ended up succeeding in bringing silk production to Connecticut, where others had failed. One was Nathaniel Aspinwall, a horticulturalist. In the 1750s Aspinwall planted mulberry trees at a nursery he owned in Long Island and later in Mansfield and New Haven, Connecticut. Aspinwall also raised and distributed to customers the silkworm eggs needed to produce the caterpillars and cocoons.

The second individual was Ezra Stiles, president of Yale College, who kept a diary of his silk-raising activities from 1763 to 1790. According to Edmund Morgan’s 1962 biography, Stiles was obsessed with the concept of silk production and found it “a kind of El Dorado to lure the prudent and industrious as surely as others were lured by a fast horse or a legend of gold in the hills.” Stiles experimented with silkworms and production, going so far as to name some of his worms with monikers such as General Wolfe and Oliver Cromwell. In the 1780s he formed a company that promoted silk production through churches throughout the state. He shipped seeds and planting instructions to fellow ministers at Connecticut parishes. The ministers were to plant the seeds and cultivate the young trees. After three years, each minister was to distribute one quarter of his trees free to local families while continuing to cultivate the rest. Because mulberry trees could grow as tall as 30 or 40 feet, they were planted in orchards, along roadways, or in hedges, in an attempt to control their growth.

While red mulberry trees are native to North America, silkworms preferred the leaves of the imported white mulberry trees. They also tolerate and will eat the imported black mulberry. The white mulberry was not fussy and grew easily in the often-rocky Connecticut soil. However, its leaves could not be harvested until the tree was five to eight years old. One acre of young trees could feed 540,000 worms; once fully mature, those trees could provide enough nourishment for a million silkworms.

Feeding the silkworms, Cheney Brothers, Manchester, ca. 1880s, 1979.25.33 – Connecticut Historical Society

A Laborious Business

By the early 1800s Connecticut was a national leader in silk production and by 1840 was producing three times as much silk as any other state. In Mansfield alone in 1825, three-quarters of all households were involved in silk production. Families were producing from as little as five pounds of silk to up to 500 pounds per year. There were so many mulberry trees in town that some owners rented out their orchards, selling shares that represented a portion of the leaves that could be harvested.

While quantity was high, however, quality was a problem. “The reeling was very poor,” wrote L.P. Brockett in his 1876 history of silk (The Silk Industry in America, George P. Nesbitt & Co.) “The threads, when wound, spun, twisted and dyed, were uneven and gummy.”

Raising the worms was time-consuming, and reeling the thread onto a spool was even more challenging. David Rossell, in his 2001 unpublished doctoral dissertation on the silk and mulberry craze, noted that the amount of leaves the silkworms consumed could reach “frightening quantities.” One ounce of eggs would produce 40,000 worms, which would grow in a series of stages over several weeks. In the first stage, which lasted four days, the 40,000 worms only consumed eight pounds of leaves, but by the final stage, which took seven days, they consumed 15,000 pounds. During this time the worms needed to be protected from birds, insects, and rodents, and the worm’s excrement had to be collected and removed to prevent disease. Once the cocoons were spun, the cocoons were cured in an oven to kill the moths before they could emerge and puncture the silk threads of the cocoons.

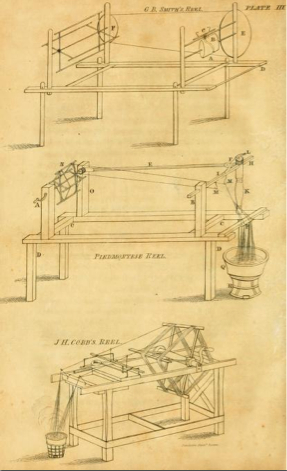

Silk reels from A Manual Containing Information Respecting the Growth of the Mulberry Tree by J.H. Cobb, 1833

Women usually tended to the silkworms and also reeled the thread. “Everything, it is admitted, depends on the reeling,” wrote William Kenrick in an 1835 silk-growing manual. The cocoons were heated in near-boiling water to remove a fibrous outer coating and then carefully reeled, usually on a specially developed silk reel. A bar attached to the reel distributed the thread as it came out of the water. Stossel explained that the bar needed to be moved back and forth so that when the silk played out upon the spool, each strand would lie crosswise atop the others. This was necessary to prevent the silk threads from sticking together and tangling. The water had to be just the right temperature, and the spinner needed to be vigilant in adding new filaments to the reel and cocoons to the water. The process took years of experience to master. Too often Connecticut women did not have the time, and younger children who were sometimes assigned the task lacked the maturity and training.

Unless the process went smoothly the silk would be uneven in size and sported fluff and even bits of cocoon and other waste. Cloth woven from such substandard silk presented an uneven appearance. As textile mills began to develop in the 1820s mill owners found it easier to import raw silk supplies from Europe and Asia than to depend on domestic suppliers, even in Mansfield, where the first mill in the nation went into operation in 1810. Meanwhile, the demanded for finished silk products was rising, and in 1824 the U.S. was importing more than $7 million in silk clothing and other products.

Dreams of Wealth Fuel a Market Frenzy

Despite the inferior quality of domestic silk and mills’ preference for foreign imports, a mulberry or silk craze emerged in the 1830s. It may have been spurred by the arrival of a new species of mulberry, the morus multicaulis. Originally propagated in Asia and the Western Pacific, the multicaulis grew far more rapidly than the other mulberry species. It also had stalks and branches that drooped close to the ground and wide leaves several times larger than those of other species. This eased the time and expense of harvesting, prompting promoters such as Edward P. Roberts, who wrote an 1839 mulberry tree manual, to suggest these costs could be cut up to 90 percent.

And there were many boosters. Congress, worried about the balance of trade in luxury items, commissioned a manual promoting silk production that was published in 1828; owners of nurseries that sold mulberry trees also wrote manuals. State legislatures, including Connecticut’s, offered new financial incentives or bounties that would be paid both to the growers of mulberry trees and for the number of silk reels produced. Many of the nation’s newspaper readers were farmers, and the publications featured numerous stories promoting silk production. Hardly anyone mentioned the many real difficulties of sericulture.

By 1830, John D’Homergue and Peter Duponceau reported to the U.S. Department of Agriculture that “suddenly and by a simultaneous and spontaneous impulse the people of the United States have directed their attention to this source of national riches…Everywhere, from north to south, mulberry trees have been planted and silkworms raised.” The Niles Weekly Register, based in Baltimore and considered by historians to be one of the nation’s most influential newspapers of its time, reported that at one agricultural fair more than 70,000 mulberry trees had been entered for various prizes.

As the 1830s progressed prices for the trees soared, as did profits for those selling them. By 1837 a new publication, the Silk Culturist, listed for sale two million white mulberry and 320,000 multicaulis trees. A Hartford nursery sold 300,000 trees in one year. Meanwhile, the Farmers’ Register, a newspaper published in Petersburg, Virginia, reported in its January 1837 issue that one farmer invested $17.50 in mulberry trees and made a $2,500 profit. A sale in Germantown, Pennsylvania of 260,050 trees netted $81,218. Nurseries that could charge $4 for a hundred multicaulis in 1834 could get $10 the next year and $30 by 1836.The New England Farmer reported, “We hear daily reports of individuals who have made their thousands and tens of thousands of dollars and the storekeeper, farmer, mechanic, etc. rush from their useful employment into the grand speculation.” Another writer exclaimed: “the product increases too fast – we grow rich too rapidly.”

By the 19th century this kind of speculative fever was not new to either American or other economies. In the 1600s the Dutch had experienced tulip mania, in which prices rose sky-high for tulip bulbs. Arthur Cole, in his 1926 article “Agriculture Crazes: A Neglected Chapter in American Economic History,” noted that speculation of various crops was common during this period in America. He described several such speculative phenomena: “Merino mania” surrounding a Spanish-bred merino sheep that produced highly-sought fine wool; “Berkshire fever” involving a hog that produced fine quality bacon; and the Rohan potato, which from a single tuber could produce 50 pounds of tubers. Each new product was introduced to wild acclaim, causing prices to climb to unsustainable levels until there was an inevitable price collapse. Cole quoted one writer of the time who observed that “your sober farmer is after all a little tinged with speculative fever whenever exotic plants or animals are brought forward.”

The mulberry speculation lured lawyers, physicians, merchants, and such prominent people as Daniel Webster. Prices for mulberry trees reached the point where they were considered more valuable for sale than they were to harvest for silkworms. Even a futures market developed, with owners selling notes of agreement to later purchase trees.

Pierced silk cocoons, Cheney Brothers, Manchester, ca. 1920s, 1987.223.1 – Connecticut Historical Society

Along with the speculators came the frauds. Some purported to sell multicaulis seeds but substituted instead turnip or other seeds. Others sold silkworm eggs that came from fish or even were made of beeswax. One of the strongest charges of fraud was leveled against one of the biggest proponents of domestic silk production, Samuel Whitmarsh of Northampton, Massachusetts, who wrote a sericulture manual and had a major nursery. Whitmarsh was accused of selling multicaulis seed for $480 a pound when the product was actually white mulberry seed worth $15 a pound at most. According to Rossell, Whitmarsh put up only a “feeble defense,” which ultimately became pointless when all of his holdings were wiped out by the coming crash in mulberry prices.

Other key players in the waning days of the craze were Ward Cheney and his brothers Frank, Ralph, and Rush. The Cheney Brothers began growing mulberry trees at their farm in Manchester, Connecticut, and a second farm in Burlington, New Jersey. They made huge profits and at one time owned 100,000 mulberry trees. In 1838 two of the brothers sailed to Europe, where they bought 65,000 trees and boasted they would make a return of 700 percent. But many of the trees died in shipping.

The men returned to Europe in 1839 and bought even more trees. This time the trees made it, but they arrived just as prices were falling and panic was setting in. The Cheneys eventually declared bankruptcy but recovered to develop in Manchester what eventually became the premier silk textile plant in North America (See Hog River Journal, Spring 2005).

The Mulberry Craze Collapses

Historians do not make clear what caused the collapse in mulberry prices. The fall came after the general financial panic of 1837, which had actually caused mulberry prices to soar as investors took their cash and used it to buy more trees, which seemed a safer haven. Much of the blame has fallen on boosters who downplayed the labor involved in silk production while over-inflating the potential profits. Another factor was that the multicaulis was poorly equipped to weather the harsh winters of the northeastern United States.

Through 1839 prices fell at alarming rates. Trees that at the beginning of the year could fetch $1 to $1.25 by the end of the year could be had for 2 to 4 cents. One auction of 30,000 multicaulis trees that would have sold for $20,000 just a few years before now had no takers. Many nurserymen began burning the trees or using them for compost.

Some speculators faced ruin. According to Brockett’s 1876 history, one group of investors on the east coast loaded their entire inventory on a ship that they considered unseaworthy, bought insurance on the cargo, and sent it to New Orleans and up the river to Indiana. They were shocked and devastated when the worthless trees reached their destination.

No place was struck harder by the panic than Connecticut, especially Mansfield. Not only did many lose money, but the financial collapse was followed in 1840 by a harsh winter that killed many of the trees. In 1844 blight wiped out virtually all of the remaining multicaulis. Connecticut farmers had had enough.

Efforts to revive the domestic silkworm crop later were tried and failed in California. After the 1840s, while demand for silk remained strong, raw materials for its production were imported. Eventually the emergence of artificial fabrics destroyed U.S. silk production once and for all.

On a June day in 1881 a few sericulture veterans gathered at a home in Mansfield to reminisce about the old days, according to an account in the Willimantic Chronicle. Each speaker recalled how they and their neighbors had cultivated the trees, nurtured the worms, and spun the thread. They wondered what had gone wrong. Joseph Conant, who had had his own ups and downs over the years in the silk business, had heard enough. “Instead of cultivating our hearty trees and improving ourselves with patience in the reeling our excellent cocoons,” he said, “we made haste to be rich.”

No one disagreed with him.

Bob Wyss is an associate professor of journalism at the University of Connecticut who lives in Manfield and has authored two books and numerous articles.

©Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 8/ No. 3 Summer 2010.