By Richard DeLuca

Mankind’s dream of flying is ancient, but the reality of manned flight is quite recent. Experiments in lifting men above the Earth’s surface did not begin in earnest until the first half of the 19th century with the construction of lighter-than-air balloons filled with warmed air or hydrogen. Balloon flight, however, was subject to the vagaries of wind and weather. In the 1880s, the dirigible appeared. This innovation added a power source and a directional rudder to a cigar-shaped balloon to aid the craft’s pilot in controlling its flight path. But this technology, too, had its limitations. It was only with the advent of the internal combustion gasoline engine at the turn of the 20th century that heavier-than-air flight became a possibility. By 1908, successful test flights by bicycle mechanics Orville and Wilbur Wright had turned controlled heavier-than-air flight from a dream into a reality, and the modern air age was born.

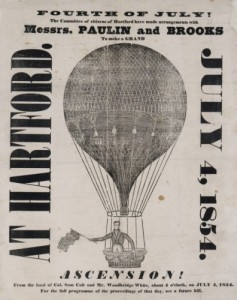

Fourth of July! : the committee of citizens of Hartford have made arrangements with Messrs. Paulin and Brooks to make a grand ascension from the land of Col. Sam Colt and Mr. Woodbridge White… Broadsides L 1854 F781f — Connecticut Historical Society

Early Air Experiments in Connecticut

The history of early aviation in Connecticut is filled with interesting episodes that mirror the evolution of aeronautics as a whole. For example, unmanned balloon flights took place in both New Haven and Hartford as early as the 1790s, and by the 1850s, balloon ascensions had become a staple of Fourth of July celebrations and traveling circus shows in towns around the state. Connecticut balloonist Silas Brooks alone made nearly 200 ascensions by the 1890s, becoming the state’s most celebrated aeronaut.

Connecticut inventor Charles Ritchel made his mark in aviation history—and the cover of Harper’s Weekly magazine—by building a dirigible of his own and sponsoring the first controlled flight of a dirigible in America in Hartford in 1878. And the history of Connecticut aviation also contains the strange case of Gustave Whitehead, a German immigrant and resident of Bridgeport whose supporters insist that he made heavier-than-air flights over Long Island Sound in a plane of his own design several years before the Wright Brothers. While evidence for the Whitehead claim remains unconvincing to many, recent investigations have uncovered wide recognition for Whitehead’s accomplishments in his own lifetime.

Crowd of spectators watching Hamilton in his flying machine, July 2, 1910. 2000.194.14 – Connecticut Historical Society

The first reliably documented heavier-than-air flights in Connecticut were not made until 1910. Charles Hamilton, already a national celebrity as a member of the Curtis Exhibition Flying Team, made the first flight of a heavier-than-air craft in New England over his hometown of New Britain as part of an Aviation Day celebration held at Walnut Hill Park on July 2, 1910. That September, aviator Frank Coffyn made several short flights in a Wright company craft above Charter Oak Park in West Hartford as part of that year’s Connecticut Fair. Similar barnstorming exhibitions were held at the Berlin Fairgrounds in 1912 and at Brainard Field in Hartford in the 1920s. Such exhibitions and air meets allowed aviators to test and perfect the technology of their engines and aircraft, while at the same time introducing the public to this latest creation of the technological revolution: the airplane.

State Passes World’s First Aeronautical Law

Connecticut Governor Simon Baldwin responded to the advent of heavier-than-air flight by signing “An Act Concerning the Registration, Numbering, and Use of Air Ships, and the Licensing of Operators Thereof” into law on June 8, 1911. The Connecticut statute was the world’s first aviation law, and it quickly became the model for similar laws in other states. The law was enforced at first by the Secretary of State, and later by the Commissioner of Motor Vehicles, who for a while doubled as the state’s Commissioner of Aviation. In 1927, Connecticut established a separate Department of Aviation to regulate the growing number of pilots and aircraft registered in the state. It was the first such department in the nation and a clear indicator that the airplane was here to stay.

The Early Aviation Industry

The pioneering days of motorized flight in Connecticut also included several attempts at creating an early aviation industry in the state. Hamilton’s inaugural flight in 1910 inspired fellow New Britain aviator and mechanic Nels Nelson to build a half dozen aircraft and engines of his own design, which he then tested and sold. But Nelson’s failure to secure a United States Navy contract for a two-engine seaplane put an end to his aeronautical enterprise. In 1913, a group of New Haven businessmen incorporated the Connecticut Aircraft Company, the state’s first public aircraft enterprise. Though organized to manufacture heavier-than-air craft, the company found itself building balloons and dirigibles for the US Navy instead. Following World War I, the company was unable to attract further business and was dissolved in the 1920s.

In 1925, Frederick Rentschler established the Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Company in Hartford, and Connecticut became home to one of the most successful aviation corporations in the world. Former president of the Wright Aeronautical Corporation of New Jersey, Rentschler was an astute businessman and visionary. Rentschler believed that the future of aviation lay in aircraft capable of carrying a large number of passengers great distances at ever-faster speeds. To do so required a more reliable, more powerful aircraft engine than was currently available, and this was where Rentschler focused his energies.

Within a year, Rentschler and his team had designed the air-cooled, radial Wasp engine, which together with its successor, the Hornet, provided just what the aviation industry needed: increased power and reliability at a low relative weight. Both engines proved extremely successful. By 1929, Pratt & Whitney Aircraft had outgrown its Capitol Avenue plant in Hartford, and Rentschler moved the company to new headquarters on a 1,100-acre site in East Hartford, which included room for further expansion and an airfield to flight test his engines. Pratt & Whitney Aircraft was on its way to becoming one of the state’s largest employers.

In the 1930s, commercial airline service became an accepted mode of transportation by the traveling public. Because of Connecticut’s small size, however, residents wishing to undertake long-distance air travel had to journey to New York or Boston for access to transcontinental and overseas flights. Colonial Air Transport provided regional service, flying passengers and cargo between New York and Boston with an intermediate stop at Hartford’s Brainard Field. Colonial Air Transport later evolved into American Airlines, which maintained operations in Hartford until the 1950s.

As air service expanded, municipal airports were also established in Bridgeport, Danbury, Meriden, and New Haven, and small, privately owned airfields appeared around the state. In 1929, the state of Connecticut purchased land in Groton for Trumbull Field, the first state-owned airport. Trumbull Field became the home of the Connecticut Air National Guard and was used mainly for military purposes.

World War II Stimulates Innovation and Growth

Air power played a significant role in the Allied victory during World War II, and Pratt & Whitney Aircraft supplied much of that power. By the end of the war, Pratt & Whitney Aircraft had produced more than 350,000 engines for military use—more in number than any other American manufacturer and, in total horsepower, one half that of America’s combat air forces. In the meantime, Pratt & Whitney Aircraft became a division of the United Aircraft Corporation, which also manufactured the latest in aviation technology, the helicopter, invented by Igor Sikorsky in 1939.

During the post-war decades, Pratt & Whitney Aircraft continued to manufacture aircraft engines for commercial use and was also involved in the development of jet engines. During the 1950s, when government optimism in the peaceful uses of nuclear power was at its peak, Pratt & Whitney even investigated the possibility of using nuclear power in commercial aircraft at its Connecticut Aircraft Nuclear Engine Laboratory in Middletown.

Murphy Terminal, Bradley Airport, Windsor Locks – Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

Post-War Commercial Travel

The focus of commercial air travel in post-war Connecticut was Windsor Locks’ Bradley Field, an active Army air base during the war that was turned over to state ownership in 1946. The airfield was named after 24-year-old Lieutenant Eugene Bradley, who was killed on the site during a training exercise in 1941. Since the 1950s, Bradley Airport has undergone several expansions, including the addition of an international terminal. Despite an effort in the 1970s to promote construction of a second jetport in eastern Connecticut, Bradley International Airport remains the state’s only major commercial airport. It is owned and operated by the Connecticut Department of Transportation, which also manages several smaller state-owned airports.

Richard DeLuca is the author of Post Roads & Iron Horses: Transportation in Connecticut from Colonial Times to the Age of Steam, published by Wesleyan University Press, 2011.