Sol Bidek’s family lived in a tenement on Market Street in Hartford. They waited several days for word from New York. Finally, they got the news: their sister was safe. The young garment worker had not been killed in the horrific Triangle Shirtwaist fire.

The disaster occurred in the New York City garment factory on March 25, 1911. One hundred forty-six workers perished, mostly young Jewish and Italian women, some as young as 14. Their escape from the inferno was blocked by poor building construction, a lack of adequate fire escapes, and an exit door the boss locked, workers said, to keep employees from stealing the goods.

The infamous Triangle Shirtwaist fire also had another Hartford connection—one of the many acts of bravery that saved lives that March day. George LeWitt was a Hartford High School graduate whose family lived on Windsor Street. On the day of the fire, George was studying law at New York University. He was in a school building directly across from the Triangle shop when he and other students heard workers’ screams and saw bodies falling. George and others raced to the roof and extended ladders to the desperate garment workers. The students’ actions saved at least forty young women.

Reports of the tragedy rocked the country. Newspapers filled their pages with shocking descriptions of working girls flinging themselves to their deaths from the tenth floor of the Triangle building. Authorities lined up badly burned bodies in a makeshift morgue; it took days to identify those burned beyond recognition. (The names of the final six victims were only ascertained in 2011.) Triangle owners Max Blanck and Isaac Harris never spent a day in jail, and even when they lost a 1913 civil suit, the company’s insurance policy awarded the two men more than they paid out in fines to the victims’ families.

The Triangle Shirtwaist tragedy sparked union organizing efforts and a wide range of new safety laws despite manufacturers in Hartford and throughout the nation moving vigorously to block those reforms. If workplaces are safer today—and they are, thanks to state and federal OSHA laws and labor unions’ vigilance—it is in part because of the Triangle victims.

Early 20th-Century Worker Safety in Connecticut

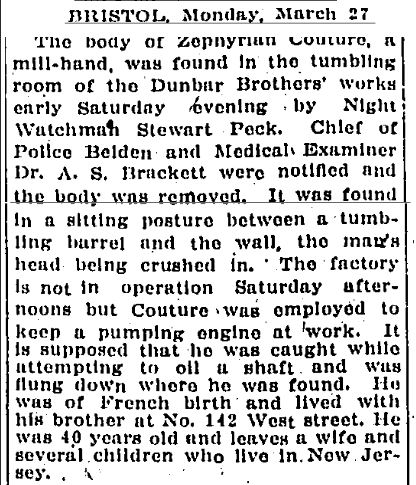

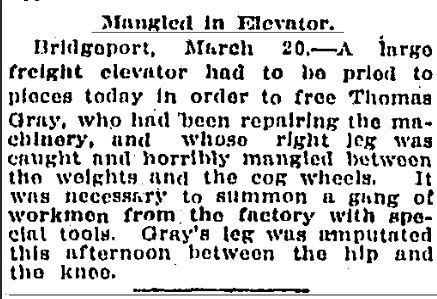

In 1911, Connecticut workplaces were extremely dangerous. On the very same day as the Triangle fire, Hartford’s Zephyriah Couture was crushed to death while he oiled a pumping engine at the Dunbar Brothers factory. In fact, during the thirty-day period before and after the Triangle disaster, fires destroyed five Connecticut businesses, causing hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages. Couture and at least six other workers—mechanics, laborers, and trolley car conductors—died in separate incidents around the state. Others became permanently disabled, like Bridgeport worker Thomas Gray whose leg required amputation after an accident during the repair of a freight elevator.

At Hartford’s state capitol, debate raged over safety legislation and other laws that protected workers’ rights to organize effective unions. A West Hartford lawmaker pressed for tough new safety standards, charging that Connecticut’s factories and hotels were the worst in New England. The few fire laws that existed, he reported, lacked enforcement. A spokesman for the Manufacturers’ Association, however, thought the present laws sufficient. A legislative move to reduce children’s work hours to 58 hours a week received support from those who feared for the minors’ health and safety, but State Comptroller Thomas Bradstreet opposed the bill, arguing that “the boys and girls of the factories will take care of themselves.”

The growing movement for worker safety had many allies, which helped, in part, to offset the power of the big business lobby to obstruct reforms. Assistance came from sympathetic legislators including State Senator Thomas Spellacy (a local attorney who also defended striking workers arrested on picket lines), Consumers League head Mary Welles, and Rev. Rockwell Harmon Potter, pastor of Center Congregational Church, who spoke in the pulpit and at the state house in favor of labor and safety law improvements.

But working people themselves really led the fight for safer jobs. As the famous union organizer Rose Schneiderman told a New York crowd just days after the Triangle fire: “The life of men and women is so cheap! And property is so sacred! Too much blood has been spilled. I know from experience it is up to working people to save themselves. And the only way is a strong working class movement.”

Connecticut’s Working Class Organizes

Sage Allen delivery truck, Market Street, Hartford, ca. 1913 – Connecticut Historical Society

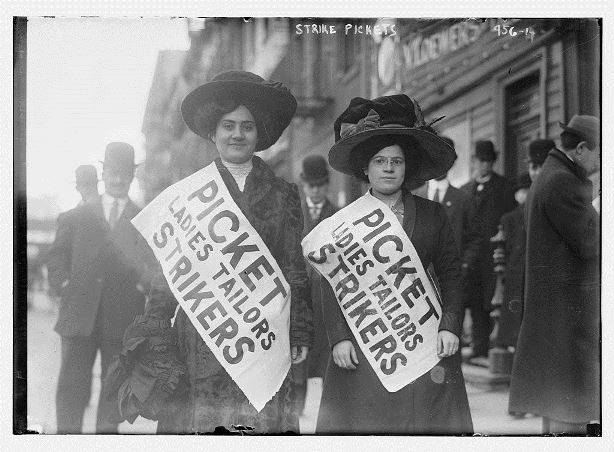

Hartford’s Rebecca Weiner took that charge seriously. Management fired her from the Sage Allen department store for trying to organize a union. Three hundred Hartford tailors at ten clothing stores were then locked out of their jobs when they refused to handle work from Sage Allen. Weiner and the other alteration tailors exposed the “insanitary conditions” at the store, according to the president of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU). Hartford shops, the union reported, had no fire escapes even though they operated many floors above street level. Rebecca Weiner argued that without a union, “no working girl could ply her honest trade in the…polluting atmosphere that environs her struggle for a living wage and decent working conditions.” Despite losing this strike, the union survived and continued organizing immigrant workers in Hartford.

Today, the fight continues for safe workplaces. The labor/community coalition known as ConnectiCOSH stresses that workers need the proper protections, the right tools, complete training, and independent monitoring to keep them safe. But accountability is the key to making sure that companies require workers to “do the job safe, not just quick,” according to ConnectiCOSH spokesman Steven Schrag. The group holds CEOs personally responsible for providing adequate safety and health programs in the workplace.

In Hartford’s Bushnell Park, near the Civil War arch, is a new Workers Memorial monument. Its dedication took place a few weeks after the 2010 explosion at the Kleen Energy construction site in Middletown that killed 6 workers and injured more than 50. On the memorial is a quote from Mother Jones, who organized workers during the time of the Triangle tragedy. It is a sentiment in need of remembrance: “Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living.”

Steve Thornton is a retired union organizer who writes for the Shoeleather History Project