By Richard DeLuca

The rise of the industrial age in the early 19th century helped create a national economy in the new American republic, and transportation improvements were essential to its health. While the construction of turnpike toll roads in most states—including Connecticut—connected inland market towns with port communities, it proved impractical to ship heavy, bulky goods overland on dirt turnpikes. To transport such goods, many states built artificial inland waterways called canals.

Erie Canal Success Spurs Connecticut to Follow Suit

One of the first and most successful was upstate New York’s Erie Canal. Completed in 1825, it ran from Albany to Lake Erie and, despite its astounding construction cost of $7 million, was an immediate financial success, collecting $1 million in toll revenue in its first year. The Erie’s success sparked a canal fever in other states, including Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Virginia, and Connecticut. By 1840, these and others states had built more than 3,300 miles of canals. Unfortunately, few if any of these projects achieved the success of the Erie.

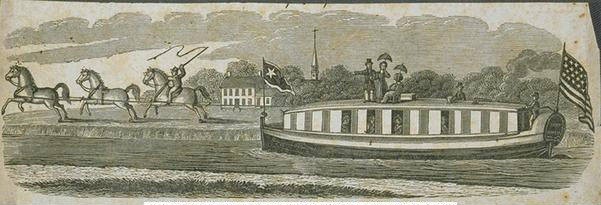

Horse drawn boat on the Farmington Canal, John Warner Barber print, 1820s, 1992.139.16 – Connecticut Historical Society

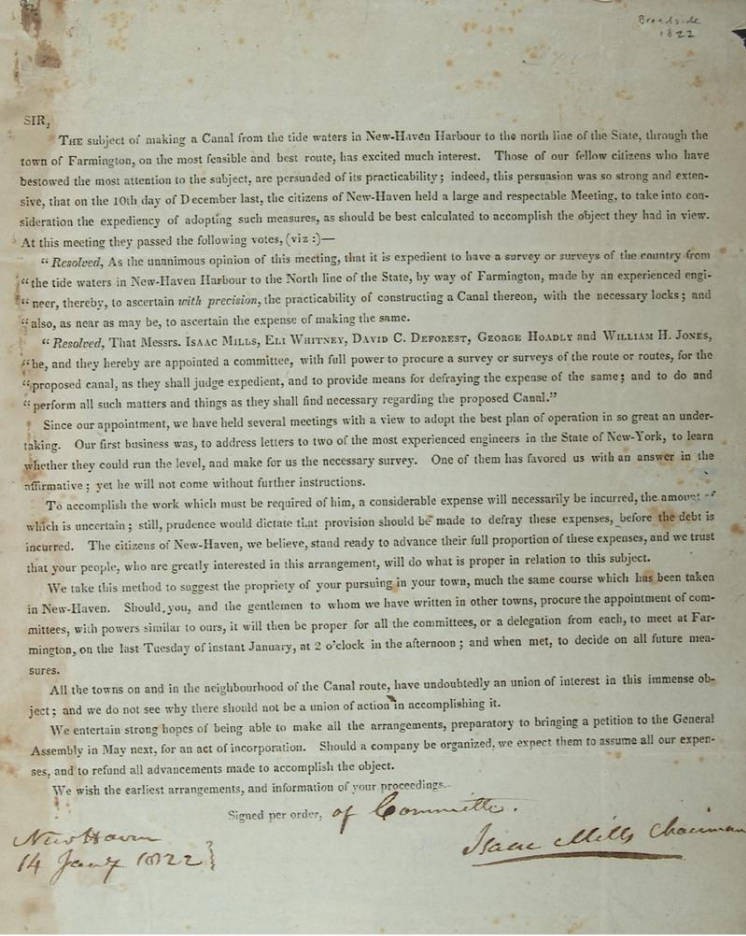

At the height of canal fever, the Connecticut Legislature granted charters to private corporations for the construction of six canals in the state: the Farmington Canal (1822), the Ousatonic Canal (1822), the Sharon Canal (1823), the Enfield Canal (1824), the Quinebaug Canal (1826), and the Saugatuck & New Milford Canal (1829). Despite the enthusiasm of their promoters, four of these projects never raised sufficient funds to begin construction. Only the Farmington Canal and the Enfield Canal were eventually built. The most ambitious canal project undertaken in New England, the Farmington Canal extended from tidewater in New Haven north to Granby, where the route continued into Massachusetts as the Hampshire & Hampden Canal, to a final destination at the Connecticut River in Northampton—a total distance of 80 miles.

Work Starts but Financing Lags

Excavating the 20-foot-wide by 4-foot-deep canal required moving 4 million cubic yards of earth and rock, using tools no more sophisticated than homemade shovels, wheelbarrows, and horse-drawn wagons. Hundreds of Irish itinerant workers, who had previously worked on the Erie Canal, and farmers along the projected route worked on the waterway.

Sir, The subject of making a canal from the tide waters of New-Haven harbour to the north line of the state, through the town of Farmington … has excited much interest…, 1822. Broadsides S 1822 F234s — Connecticut Historical Society

From New Haven to Northampton, the canal’s elevation rose and fell more than 500 feet, and keeping the water level throughout the route required the construction of 60 locks, each 75 feet long and 12 feet wide. Built of heavy stone and timber, the locks controlled the flow of water with two sets of hefty wooden doors, each with two small openings through which water could be let into or out of the lock.

While New York had used the borrowing power of the state to fund the Erie Canal, neither Connecticut nor Massachusetts provided financial assistance for the Farmington Canal projects. Instead, capital came solely from the stockholders of the two corporations chartered to build them. As a result, raising funds for the two projects proved difficult from the start. To help raise money, Connecticut allowed the incorporation of several canal banks, a portion of whose assets could be used to purchase stock in the canals. Still, as construction progressed, cash flow problems persisted, and payments to contractors and landowners were repeatedly overdue.

The Canal Opens

The first portion of the Farmington Canal, from New Haven harbor to Farmington, Connecticut, opened to traffic in 1828. To commemorate the occasion, four gray horses ridden by four African American boys pulled the packet boat James Hillhouse (named for the president of the canal company) while 200 dignitaries sipped refreshments on deck. By 1830, the entire route in Connecticut was operational, and as apples, butter, cider, and wood flowed southward to New Haven, imports such as coffee, flour, hides, molasses, salt, and sugar headed to towns upstream.

Even after the Connecticut portion of the route opened, funding difficulties continued to delay the remainder of the project, and the canal was not completed through to the Connecticut River at Northampton until 1835, a decade after construction began. Heavily in debt by then, the two companies reorganized into one corporation, the New Haven & Northampton Company, at a loss of more than $1 million to the original shareholders.

A Short-lived Heyday

Business on the New Haven & Northampton Canal increased steadily during the first years of full operation, and as goods and passengers traversed the route, towns and businesses along the canal prospered. Shareholders in the new canal company, however, did not. During the company’s first four years of operation, damage to the canal and its structures from heavy rains and overflowing streams was exceptionally high, and toll revenues covered barely 20% of the company’s expenses.

Unfortunately, that experience proved typical. For the 10 years of its corporate existence, the New Haven & Northampton Canal recorded a profit only once. Beginning in 1845, the company phased out canal service along the Connecticut portion of the route, and then amended its charter to allow the construction and operation of the 19th century’s greatest transportation invention: the railroad.

Richard DeLuca is the author of Post Roads & Iron Horses: Transportation in Connecticut From Colonial Times to the Age of Steam, published by Wesleyan University Press, 2011.