By Emma Wiley

In the 1930s, the Wells Historical Museum—founded by Albert B. Wells, along with his brothers Channing M. and J. Cheney Wells—purchased a farm in Sturbridge, Massachusetts to create a living village museum for Wells’ antiques collection. The museum initially named the attraction Quinebaug Village and began searching for historic buildings to move to the farm to build a pseudo-19th century New England-style town. Between 1938 and 1964, the museum physically moved at least five buildings from around Connecticut to complete “Old Sturbridge Village.”

Since long before the advent of motorized vehicles, house moving has been a relatively common practice. People moved houses or other buildings for numerous reasons, including historic preservation. To protect the structure and historical integrity of the buildings, Old Sturbridge Village (OSV) used a variety of moving methods such as complete deconstruction, partial deconstruction, and in one piece. In many cases, from Thompson to Goshen, dozens of people came to watch the historic buildings leave their Connecticut communities. Despite their current location in another state, OSV’s Connecticut buildings still have a multitude of stories to tell about the communities that built them.

Miner Grant Store

The Grant Store in Stafford Springs during deconstruction, July 1938 – Old Sturbridge Village Research Library

For Stafford Springs, the Miner Grant General Store was not only a place to shop but also a community gathering spot to trade gossip, pick up mail, and learn about news. A physician, Miner Grant Sr. bought the business in 1802 and ran the store with his son, Miner Grant Jr. They passed the store down to a nephew, Clark Grant, and through the family until a descendent sold it to Quinebaug Village in 1938. The store operated into the 20th century—providing a range of items from food to farm tools to household goods to medicines.

The Grant store was one of the first buildings Quinebaug Village (renamed Old Sturbridge Village in 1946) moved to start creating its quintessential New England town. Workers dismantled the structure piece by piece, carefully labeling each component to make sure they knew how to put it back together. The move was memorable—one local woman, who was eight years old at the time, recalled the event as the highlight of her summer.

Fitch House

Fitch House in Willimantic prior to the move to Sturbridge, August 1939 – Old Sturbridge Village Research Library

Even though a couple of other buildings moved previously, in 1939, the Fitch House became the first dwelling house Quinebaug Village moved to their growing museum. Stephen Fitch built the first part of the house around 1737 in Willimantic for his young and growing family; Fitch (and descendants) made changes and added on extensions later in the 18th and early 19th centuries. The house originally stood on the western end of Main Street, across from the Old Willimantic Cemetery.

Like with the Miner Grant store, Quinebaug Village dismantled the house, transported the pieces to Sturbridge, and reassembled the structure. Unlike the case with many of the other buildings, there are no known photographs of the Fitch House moving process. In fact, Quinebaug Village moved the house before opening their attraction to the public.

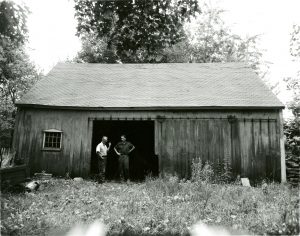

Hervey Brooks Pottery Shop

The Hervey Brooks Pottery Shop might be one of the most unique structures Old Sturbridge Village moved during the 20th century. Hervey Brooks built the shop around 1818 in the South End neighborhood of Goshen for his red earthenware pottery making. Even though red earthenware was going out of style, Brooks continued to make pottery until his last kiln firing in 1864 at age 85. He sold some of his various wares and traded others for items his family needed or could resell. In addition to pottery making, Brooks boasted a large variety of income sources—from farming to peddling goods to running a tavern.

In the process of moving the pottery shop, workers found remnants and evidence of a kiln at the shop. Today, the former location in Goshen is a historic industrial archaeological site listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In addition to his pottery shop, visitors can find evidence of Hervey Brooks in other parts of OSV, such as his bricks that make up the smoke house in the Freeman Farm Garden.

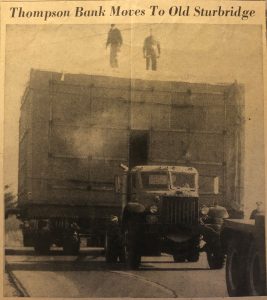

Thompson Bank

By the time Old Sturbridge Village started looking for a mid-19th century New England bank, many of the historic structures were gone or significantly altered. The Connecticut General Assembly incorporated the Thompson Bank on June 5, 1833. Over the next 60 years, the bank experienced its share of ups and downs before the business moved to Putnam and sold the building to the town of Thompson. The town used it for various functions before selling it to the Boy Scouts of America.

In the fall of 1963, after OSV bought the building, movers jacked up and carefully boxed the 22’ x 28’ structure. Workers threaded steel rods through the plaster and used plywood to brace and provide extra structural support. Taking care to travel at only a few miles an hour and avoid congested areas, narrow roads, and low overhangs, the trip took four days in mid-November. While Thompson is not far from Sturbridge—17 miles—the carefully planned route added over 20 miles to the trip.

The Thompson Bank still lives on in the imagination of the town. Despite the neighboring church’s expansion, there is still a half-empty lot where the bank once stood across the street from the common. Thompson’s historical sign—erected by the Thompson Historical Society, the town of Thompson, and the Connecticut Historical Commission—includes mention of the move of the Thompson Bank. Finally, a few miles away, Thompson’s Makers Fair has a booth that is loosely based on the bank’s structure—an homage to the town’s lost history.

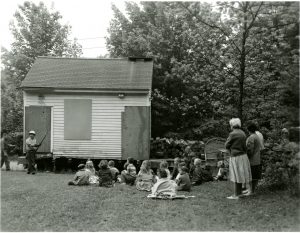

McClellan Law Office

McClellan Law Office in Woodstock during its move, May 1964 – Old Sturbridge Village Research Library

As a lawyer, presidential elector, and state legislator, John McClellan was an active man in Connecticut and the Woodstock community. In the late 1790s, he built a small building on his property on Woodstock Hill to serve as a law office where he could work, meet clients, and store his law books.

While OSV moved most of the larger structures by partially or entirely dismantling the building (except for Thompson Bank), they moved the McClellan Law Office intact. In May 1964, the Southbridge Trucking Company jacked up and lifted the office onto a flat-bed trailer. The move of the small building attracted quite the crowd—including kindergarteners and third grade classes from a school nearby. According to a local paper, the children had no qualms about advising the movers on their job and made sure they buckled their seatbelts.

Connecticut’s History in Massachusetts

There are other Connecticut structures at Old Sturbridge Village, but OSV is currently interpreting these five. Despite originating in towns dozens of miles apart, these Connecticut businesses, office, and house share an imaginary town. While these historic structures no longer live in Connecticut, evidence of their existence lives on in historic maps, photographs, and locals’ memories.

Emma Wiley is the Digital Humanities Assistant at CT Humanities and holds a B.A. in History from Vassar College.