By Steve Thornton

On May 1, 1969, Hartford’s Chamber of Commerce flanked Mayor Ann Uccello as she held up a broom on the city hall steps. This photo op for the press was the chamber’s annual Clean-Up Day: business and government united to inspire civic pride and personal responsibility among Hartford’s residents.

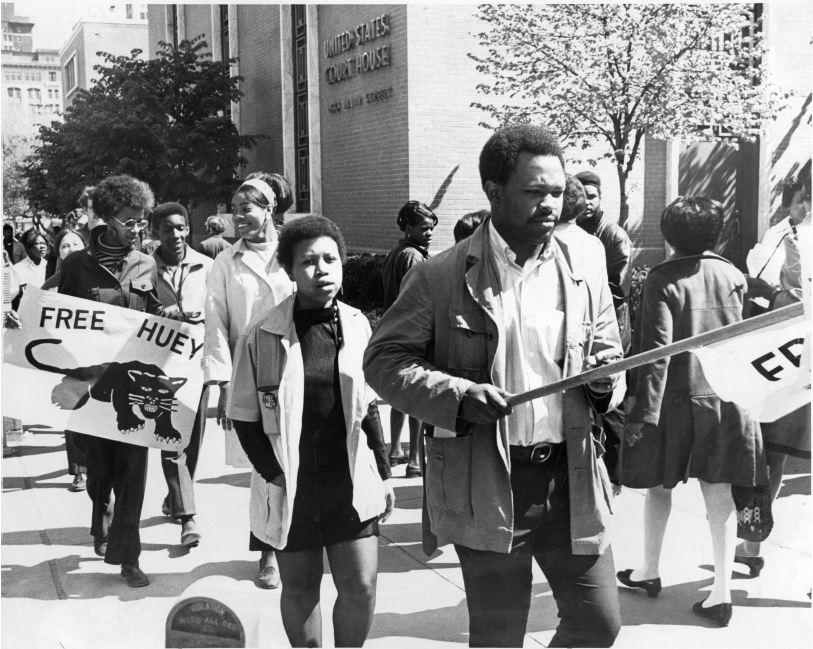

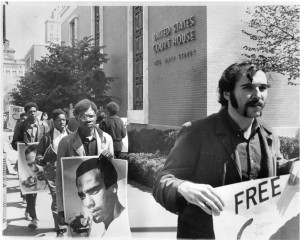

Just one block away, at the same moment, the Black Panther Party assembled dozens of young people at the Federal Building. The crowd marched, waved flags, and chanted. The Panthers, who found fertile ground for recruitment in Connecticut, did not carry brooms—or guns. The Party was responding to poverty, violence, and oppression in Hartford’s black community. Their weapon of choice was a manifesto, the ten-point program entitled, “What We Want, What We Believe.”

Protestors on May 1, 1969, in Hartford carried signs bearing a photograph of Huey P. Newton, a founder of the Black Panther party. Photograph by Ellery G. Kington – The Hartford Times Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

The Panther program called for full employment, exemption from military service, and the “immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people.” Founders Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale wrote the program in Oakland, California, in 1966. They demanded “land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.” The statement ended with the Declaration of Independence.

Survival Programs

Throughout its brief existence in Connecticut (1969–1972), the Black Panther Party prioritized community service. This was not service for its own sake, but “survival programs” undertaken while the Panthers worked to raise the political consciousness of people of color and the urban poor.

One of the most successful outreach efforts was the Panthers’ breakfast program for children. It won significant support from local grocery stores and individual donors. In Hartford, activists served breakfast at St. Michael’s Church on Clark Street. One of the church’s resident priests was Fr. Leonard Tartaglia, an outspoken critic of institutional racism and a close ally of the Panthers. In Bridgeport, New Haven, and Willimantic, school children also stopped by the Panthers’ kitchen before school for breakfast, and sometimes for clothing as well. In many areas, Panthers provided medical and other services usually unavailable to low-income neighborhoods.

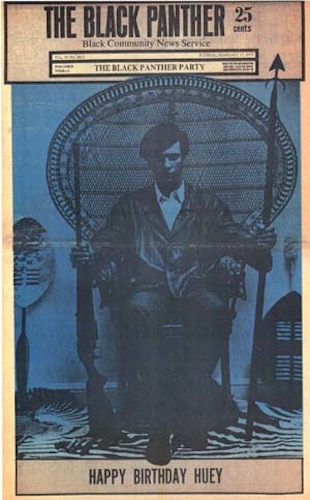

Black Panther. Vol. 4, no. 11, 1970 – From the exhibit Voices from the Underground: University of Connecticut Libraries, Archives & Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center

The Panthers also had other priorities. One of the most important was their newspaper, The Black Panther. Party leadership required all members to distribute it, and when issues hit college campuses, sales proved brisk. On New Haven and Hartford streets, police regularly arrested young Panthers for soliciting, but quickly dropped the charges. Members like George Green (17), Gwen Rhodes (16), and Willie Ledbetter (14) of Hartford all faced harassment and arrest. Declassified FBI documents subsequently revealed that J. Edgar Hoover urged police disruption of Panther newspaper production and sales. In a secret 1970 memo, local agents estimated that 4,000 copies sold each week in Connecticut.

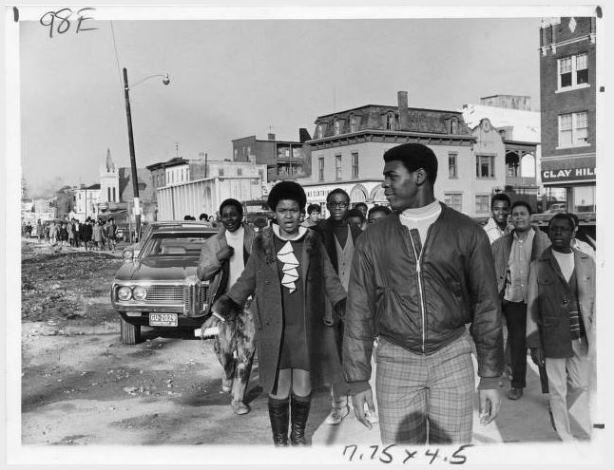

In New Haven, the Panthers organized against a new planned highway that divided the city’s neighborhoods. The Panthers argued that Route 34 brought suburbanites into the city but did nothing for the people already living there in desperate conditions. In Hartford, Panthers provided security protection for Adam Clayton Powell Jr. when he visited the city. They also advised a Weaver High School student boycott that turned into a march downtown to meet the mayor. From Storrs to Stamford, Black Panthers seemed to be on every college campus and at every anti-Vietnam War demonstration.

Weaver High School students marching on Albany Avenue, Hartford, December 1969 – Hartford Public Library, Hartford History Center, Hartford Times Collection and Connecticut History Illustrated

Life or Death

One example of Panther community service stood above the rest, and was literally a matter of life or death. Hartford officials promised the public housing tenants of Charter Oak Terrace in 1968 to fix the overflowing Park River. The river caused the drowning deaths of several children when the water rose to a dangerous level. In 1969, while the tenants still waited for action, another child drowned. This time the parents contacted the Black Panthers.

Butch Lewis and Rap Bailey advised the parents as they picketed in the street, blocking traffic. The Hartford police arrived to break up the disruptive nonviolent action and threatened arrests, but the parents pledged to come back the next day. Return they did, and the attention they attracted increased their numbers.

The Charter Oak neighbors met with Governor John Dempsey. Further river inspection discovered a blockage downstream that should have been dismantled several years earlier. Workers removed the obstruction and the river’s water level lowered to its normal, safe level.

What none of the participants knew at the time was that the FBI was on the scene. Agents sent “urgent” teletype memos directly to J. Edgar Hoover. Specifically because of the Panthers’ involvement, the Bureau feared “possible racial violence” as a result of this peaceful protest.

Government Spying

From the beginning, local police departments and the FBI spied on the Panthers. The FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover placed enormous emphasis on crushing the Black Panther Party and its programs. In Connecticut, the Bureau used wiretapping and informers to prepare reports sent directly to Hoover. The effort was part of his secret (and often illegal) COINTELPRO program, which a US Senate investigation exposed as “a sophisticated vigilante operation.”

Ironically, today we know much more about Connecticut Panther activity thanks to FBI records. In January 2014, the Bureau released 1,582 pages of previously confidential reports, thanks to an FOIA request by Trinity College professor Jack Dougherty. The documents, while only a portion of the full file, showed the FBI what the Panthers were not doing: they were not sniping at police or looting. They were not coordinating riots on the street. They did not have an underground cell, nor were they in touch with foreign governments. They did procure weapons, but there was no indication that they obtained any of them by stealing.

Connecticut Panthers knew the police and feds spied on them, but the declassified files also showed that the US Army’s 108th Military Intelligence group watched the Panthers as well. The army had a secret office in the Hartford Federal Building and shared its findings with other government agencies. The military spies kept tabs on 100,000 citizens nationwide, a 1972 congressional committee discovered.

Spurred by fears of the militant Panthers, the New Haven police department illegally wiretapped 3,000 citizens and small businesses. A 1977 lawsuit uncovered the surveillance, which the department said the FBI approved. The Bureau disavowed knowledge of the wiretaps. In a 1984 settlement agreement, however, a jury awarded $1.75 million to 1,200 people who found their phones tapped by authorities.

In September 1967, city leaders—black and white—met to strategize about ways to address Hartford’s racial problems. In a photograph taken on September 22, members of the city’s influential Black Caucus announced that their main effort would be the revitalization of the Hartford Community Renewal team. Activist John Barber Jr. is in the striped hat, the third man from the right. Photograph by Einar G. Chindmark – The Hartford Times Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

The Black Panther Legacy in Connecticut

Were the Black Panthers heroes or villains? Dr. Cornel West, a leading African American scholar, credited the Panthers for “turning scared, intimidated, helpless folk into bold, brave, hopeful people willing to live and die for Black freedom.” J. Edgar Hoover, however, called them “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country.”

While there is no historical consensus on the Panthers’ legacy, one more voice warrants consideration: veteran Hartford police officer Thomas Fuller. Fuller served in 1970 as a leader of the Guardians, an African American caucus of Hartford policemen. In response to increasing incidents of “bigoted abuse” committed by white police, Fuller publicly stated that “black officers will intervene in any way necessary to constrain [police] brutality,” including the use of physical force. A few months earlier, he told an NAACP audience that if he were not a cop, he would join the Black Panther Party.

Steve Thornton is a retired union organizer who writes for the Shoeleather History Project