By Andrew Song

Yale University’s library and literary debate reputation owes much of its origins to the societies of Linonian (sometimes referred to as Linonia) and Brothers in Unity. Founded in 1753 and 1768 respectively, these two undergraduate literary societies—earliest of their kind—assembled one of the largest independent book collections in America, only to later donate them to Yale’s nascent library. In doing so, their actions inspired a new wave of interest towards collegiate library development across American higher education.

Two Early Literary and Debating Societies

Linonian and Brothers in Unity influenced campus life through more than just their books, however. The two societies maintained a friendly rivalry that involved the entire Yale undergraduate community. They competed over membership, as well as over who had more valedictorians and volumes of books. For instance, both societies claimed future US Vice President John C. Calhoun as a member.

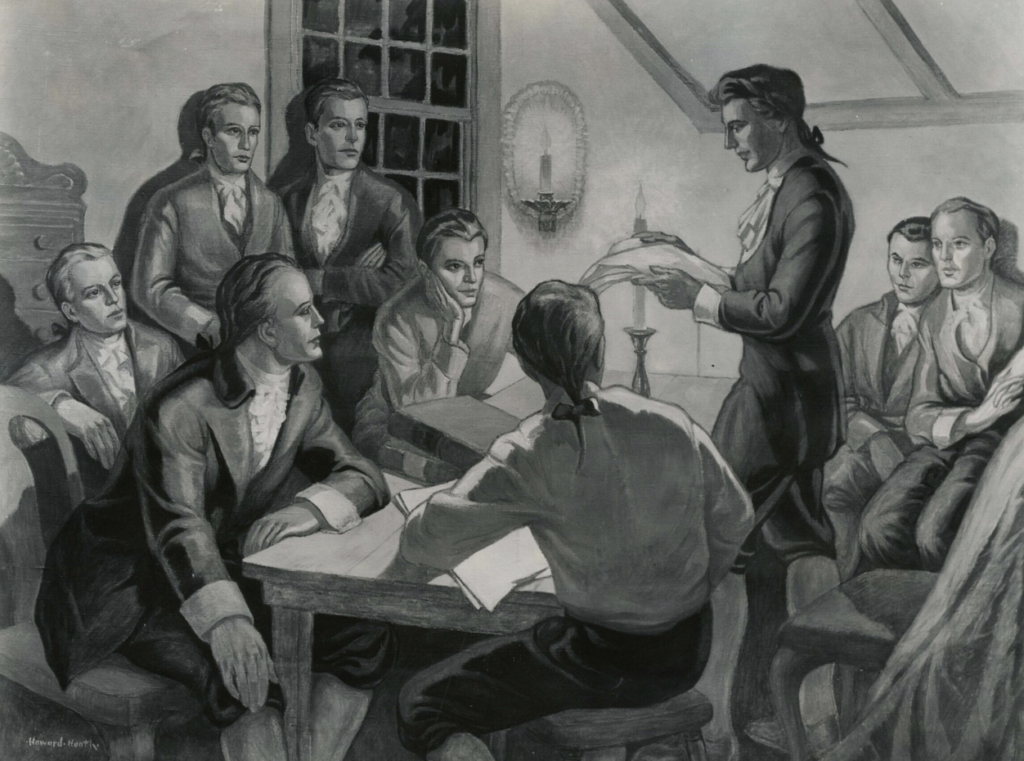

This jockeying for recognition complemented their activities. Hosting oratory competitions, a weekly forum for philosophical debates, and theatre for their memberships, “Brothers” and “Linonians” alike practiced an appreciation for healthy rhetoric and radical ideas.

Early Society Members

Participation in Linonian or Brothers in Unity led many early members to become influential in a variety of activities during the American Revolution and the development of the young United States—some even retaining their connections to literacy. During his participation with Brothers in Unity, Noah Webster (1778), became fascinated with language; penning what eventually became the foundation for the Merriam-Webster Dictionary. One of his classmates, Joel Barlow (president of Brothers in Unity in 1778) served as one of the first US ambassadors to France, but he also authored American epics such as “The Columbiad” and satires such as “The Hasty-Pudding” that remain in contemporary literary anthologies today. Barlow’s tenure in Brothers in Unity introduced him to David Humphreys (1771), who served as an aide-de-camp to General George Washington in the Continental army. Together, Barlow and Humphreys wrote satirical poems as members of Connecticut’s “Hartford Wits.”

Other members of the two societies became more involved in politics after Yale. Uriah Tracy responded to the first shots of Lexington and Concord but later became a senator for Connecticut and the state’s first president pro tempore for the US Senate. Another classmate, Oliver Wolcott Jr., served as secretary of treasury and the 24th governor of Connecticut. Wolcott’s interest in state politics stemmed, in part, from the ferocious undergraduate debates hosted by the Brothers in Unity.

Despite much of their openness as student groups, Linonian and Brothers also professed a Masonic secrecy and privacy in their activities. Nathan Hale and Benjamin Tallmadge are perhaps most famous for carrying that secrecy into their post-graduation lives. The public best remembers Nathan Hale, a member of Linonian’s class of 1773, as a Connecticut hero—hanged by British troops in 1776 for spying. At the same time, his Brothers in Unity counterpart, Benjamin Tallmadge (also 1773), stewarded the Culper Spy Ring—a circle of agents that passed vital intelligence to Washington during the Revolutionary War.

Linonian and Brothers in Unity Donate to Yale Library

Before the Civil War, when so few libraries in the United States could aptly be labeled research libraries, wealthy individuals such as Jacob Astor possessed personal collections that exceeded the inventory of many educational institutions. Recognizing this disparity, Yale released a faculty report in 1871 lamenting the neglected nature of their library—the third-oldest academic library in the country. Later that year, both Linonian and Brothers in Unity donated the tens of thousands of volumes in their society libraries to the Yale Library, increasing the college’s holdings by a significant amount. The societies disbanded shortly afterward but their act of generosity helped solidify Yale’s status as the second-largest academic library in the country.

Linonian and Brothers in Unity in the 21st Century

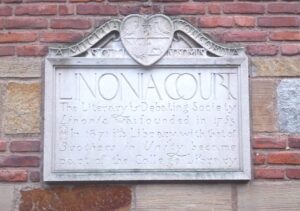

For all their contributions as some of Yale’s first student clubs and societies, Linonian and Brothers in Unity continue to maintain a presence at Yale in the 21st century. The Sterling Library at Yale maintains a reading room (recently renovated) named after these two societies. Walking through residential Branford College, students frequently pass through a courtyard named after Linonian and, in 2021, 21 Yale upperclassmen revived the Brothers in Unity society with significant support of Yale alumni. While cementing Yale’s library presence in the community, the two societies were a haven for individuals who shared a common love for intellectual vitality. By virtue of their public service and academic rigor, the societies and their students made a lasting impact on Connecticut, as well as on the country.

Andrew Song graduated with a BA from Yale University and is now a US Navy Submarine Officer assigned to the USS San Francisco (MTS-711).