By Holly V. Izard

David Humphreys was a Yale-educated soldier, politician, foreign minister, and entrepreneur. Though noted by literary historians for his poetry and writings as a member of the Hartford Wits, he is probably best remembered for his importation of Merino sheep in 1802. Indeed, Humphrey’s contributions to agriculture helped shape Connecticut’s economy in the Early Republic.

Early Life in Derby

David Humphreys, born in 1752, was the son of the Reverend Daniel and Sarah Riggs Bowers Humphreys of Derby. Both held positions of respect in the community, his father as a Congregational minister and his mother (the reverend’s second wife) by virtue of a style and graciousness that led her to be known as “Lady Humphreys.” Their house at 37 Elm Street in Ansonia (formerly part of Derby) is now a museum and headquarters of the Derby Historical Society. David grew up with the privileges that wealth afforded. He received both a bachelor’s and master’s degree from Yale and was associated professionally and socially with some of the best and brightest men during his military and political careers.

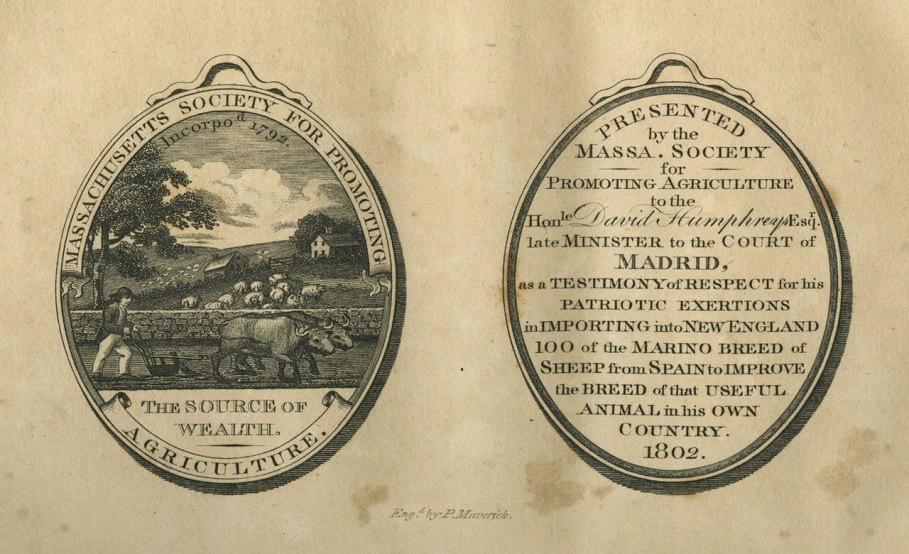

Gold medal awarded to David Humphreys by the Massachusetts Society for Promoting Agriculture, 1802

A Distinguished Career at Home and Abroad

During the Revolutionary War, Humphreys’ military talents and patriotism won General George Washington’s friendship and respect. He enlisted in the 2nd Connecticut Regiment of the Continental Army in July of 1776 and participated in the battles at Danbury and Sag Harbor, New York, in 1777. In December 1778 he was appointed as aide-de-camp to General Israel Putnam of Pomfret. He moved up the ranks to colonel. On June 23, 1780, he was appointed aide-de-camp of Washington’s headquarters staff.

The future president’s esteem for David Humphreys led to an impressive political career. From 1784 to 1786 he was a member of a United States mission negotiating commercial treaties in Europe. This placed him in the company of John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin. Back home, his constituency in Derby elected him to the October 1786 session of the Connecticut National Assembly.

As General Washington’s confidant and friend, Humphreys was present at the first presidential inauguration in 1789. From 1791 to 1796, he served as American minister to Portugal, during which time he negotiated the release of some American prisoners. He had the distinction of being the first minister appointed under the new constitution. From 1796 to 1801 he served as minister to Spain, which at the time controlled the Mississippi River and most of Latin America.

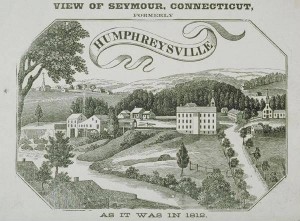

In 1797, while in Spain, Humphreys married Anne Frances Bulkley, daughter of a very wealthy English merchant, banker, and trader. When his post ended, the couple returned to the states. Humphreys purchased a fashionable house on Beacon Hill in Boston, bought a farm in Derby, Connecticut, to pursue his agricultural interests, and built a factory in the nearby town of Seymour to manufacture woolen cloth. According to Charles Brilvitch, a historian of the Paugussett Tribe, the tribe’s reservation at the falls of the Naugatuck River had been taken away so that Humphreys could construct his woolen mill there. This suggests the level of influence he enjoyed.

Gentleman Farmer

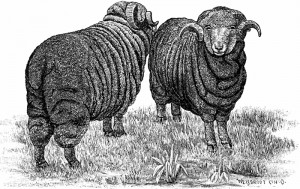

Merino Sheep

Despite his uncommon achievements as a gentleman soldier and politician, Humphreys earned broader recognition for his importation of Merino sheep to the US in 1802. This Spanish breed boasted high-quality fleece superior to that produced in Connecticut at the time. At the close of his ambassadorship to Spain, Humphreys purchased a flock of 25 rams and 75 ewes and had them shipped directly to his Derby farm. His education, experience, and great wealth offered the leisure to investigate and promote agricultural improvement. He helped to found the Agricultural Society of Connecticut in 1816 and served as its first president.

Reverend Timothy Dwight, a college friend who went on to become president of Yale, wrote of David Humphreys in his renowned Travels in New-England and New- York, a four-volume travel diary he kept of his observations during his journeys in the first decades of the 19th century. In discussing the “Manufactures of New England,” Reverend Dwight made the following observations about Humphreys’ enterprise:

Humphreysville originally named for General David Humphreys, who established the first large woolen mill in the United States here in 1806 – Connecticut Historical Society

The fabrics of the loom woven here are chiefly those whichare worn by the middle and lower classes of mankind. Beautiful cloths are however made in considerable quantities, and of such a quality as not to be distinguished from the superfine cloths of Europe. For these, the Merino sheep furnish the material. Happily for us, this useful animal, instead of declining as was expected, has visible improved in our pastures; having increased both in its size and the quantity of its wool. For the introduction of this valuable breed, the United States are greatly indebted to the Hon. David Humphries, former minister plenipotentiary at the courts of Lisbon [Portugal] and Madrid [Spain]. They are now, together with the cross-breeds, filling the country.

Indeed, the agricultural press seized upon Humphrey’s success with Merino sheep as a sign of progressive farming and the Connecticut importer’s connection to the breed endured beyond his lifetime. When his sheep landed in Derby, farmers came from far and near, and Humphrey sold the sheep to interested parties for $100 each (less than it cost him to buy them). Farmers cross-bred these superior animals with native stock, resulting in improved quality and quantity of wool. The popularity of Merinos spread nationwide and it was not long before a Humphrey’s sheep commanded $1,500 or more. It was part of his larger plan to develop the internal resources of the country: better wool encouraged men to follow his example and build woolen mills. This new industry faltered when British imports again flooded the market after the close of the War of 1812. Sleep values depreciated and many fledgling mills failed. But Merino sheep endured in popularity; by the 1830s they were a “must have” for even the most modest farmers.

David Humphreys died on February 21, 1818, in a hotel room in New Haven where he was staying while tending to the Derby Farm. He was 66. He is buried at Grove Cemetery in New Haven.

Holly V. Izard, who holds a PhD in American and New England Studies from Boston University, has written and published extensively on pre-1850 New England agriculture and social history and is curator of collections at Worcester Historical Museum in Worcester, Massachusetts.