By Nancy Finlay

Jews fleeing from antisemitic violence in Russia and Russian-occupied territories in Eastern Europe began arriving in the United States in large numbers in the late 19th century. While most arrived and initially settled in New York City, many quickly moved out into neighboring states. Like many other immigrants, some found work in factories, while others turned to farming.

Mr. and Mrs. Abraham Lapping, Jewish poultry and dairy farmers. They ran a small farm and took in tourists during the summer in Colchester – Photo by Jack Delano, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Used through Public Domain.

As early as 1882, L. B. Haas—a Jewish tobacco merchant, whose family emigrated from Holland—established the Society for the Aid of Russian Refugees in Hartford. In addition, substantial support for local Jewish immigrants came from the Baron Maurice de Hirsch, a wealthy German Jew who established a fund to help Russian and Romanian emigrants to the United States purchase farms, household furnishings, and farm equipment. The assistance from these organizations (and others) helped Jewish immigrants to purchase tobacco farms in the fertile Connecticut River Valley. Other recently arrived Jews from eastern Europe turned to dairy and poultry farming, realizing that Connecticut’s rocky soil did not lend itself to growing most crops. While they settled in Ellington, Lebanon, Norwich, East Haddam, and Newtown (among other towns)—forming close-knit communities resembling the ones they left behind in Eastern Europe—two particularly well-known groups took root in Chesterfield and Colchester.

Chesterfield’s Jewish Community

Russian Jews began settling in Chesterfield, Connecticut, a small rural community north of New London, in 1890, led by Harris Kaplan, an unordained rabbi from Ukraine. Articles in the Hartford Courant describe these early immigrants struggling to cultivate the soil and making coats for sale in Boston. In 1892, the Baron Hirsch Fund helped them build a small wooden synagogue and a cooperative creamery. There they hoped to encourage other Jewish immigrants to move to the area and take up dairy farming.

Many of the newcomers, however, lacked farming experience and did not remain in Chesterfield. Others began taking in summer boarders. The creamery managed to struggle along until 1912, when the Hirsch Fund foreclosed on the property. About 50 Jewish families remained in the area until the 1930s, working as subsistence farmers and summer boarding house operators, running a general store and a dance hall, and congregating at the local swimming hole. The synagogue was open for high holidays through the 1950s. An arsonist burned the building to the ground in 1975.

Colchester’s Jewish Community

Old man entering Jewish synagogue for afternoon services. Colchester, 1940 – By Jack Delano, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Used through Public Domain.

Colchester became home to one of Connecticut’s largest Jewish communities. Colchester’s Jewish residents established a Jewish cemetery there in 1894 and the Congregation Ahavath Achim in 1898. The congregation acquired its first synagogue building in 1902 and built a new synagogue in 1913.

By 1920, half of Colchester’s population was Jewish. Farmers organized the Colchester Jewish Farmers’ Cooperative Credit Union in 1912 and established the Colchester Farmers Produce Company in 1916. In 1911, five out of eleven high school graduates were Jewish and a Jewish girl, Rachel Himmelstein, was class valedictorian. In 1921, Himmelstein became the town’s first Jewish elementary school teacher.

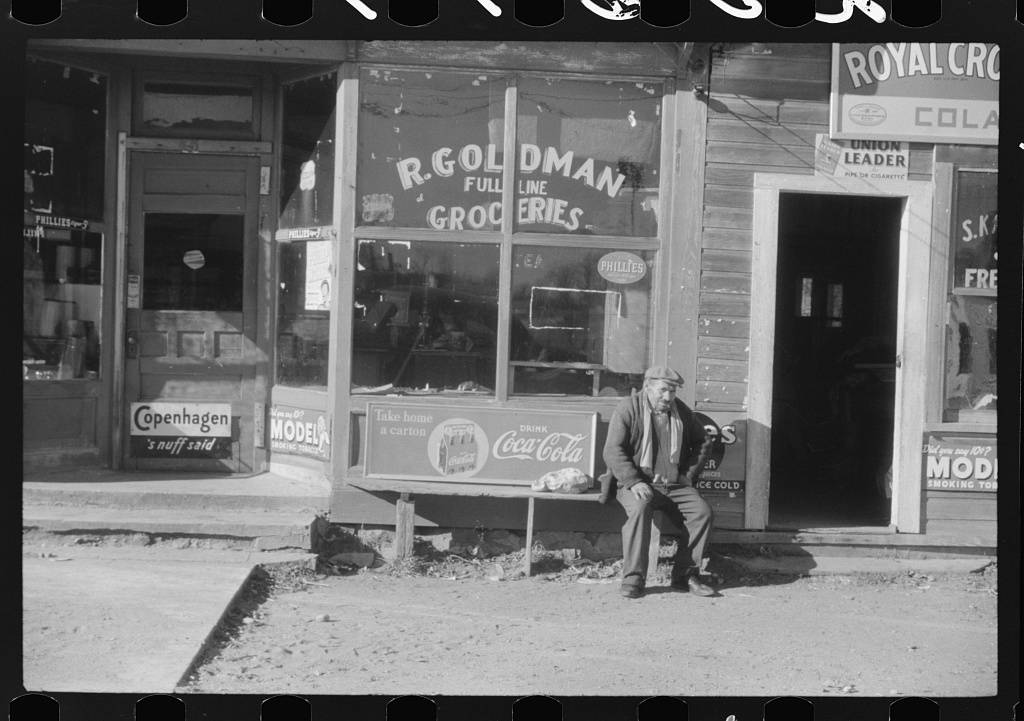

By 1940, Colchester’s Jewish residents included not only dairy and poultry farmers, but also grain dealers, physicians, dentists, pharmacists, lawyers, insurance agents, real estate agents, an automobile dealer, a trucking firm operator, the local movie theater owner, and a factory owner. Two kosher butchers and a kosher bakery supplied the Jewish population of Colchester. As evidence of the vibrant community, Jack Delano documented Jewish life in Colchester in a series of photographs for the Farm Security Administration taken in 1940.

The descendants of the original Russian Jewish farmers became an integral part of Connecticut life, often leaving the land to pursue successful careers elsewhere in the state. By 1993, only one Jewish farmer remained in Ellington, but Colchester remains home to a large Jewish community. Congregation Ahavath Achim continues to flourish to this day and still includes descendants of many of the original farmers, as well as Holocaust survivors and descendants who settled in the town following World War II.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.