This version of this article has been archived. To read the updated version of this article, please click here.

By Nancy Finlay

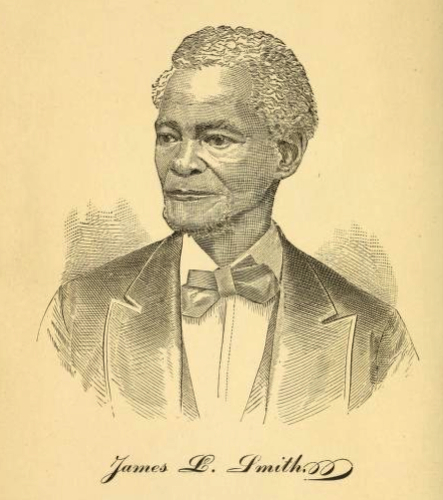

In the years before the Civil War, the Underground Railroad enabled thousands of Americans of African descent to escape from slavery. In the North and in the South, black and white people, men and women, worked together to assist fugitives on the road to freedom. One of these fugitives was James Lindsey Smith, who fled slavery in Virginia to find a new life in Connecticut.

Smith was born and enslaved on a plantation in Virginia’s Northern Neck. As a small boy, an accident left him lame and unfit to work in the fields, so he trained as a shoemaker. Throughout his training, however, thoughts of freedom preoccupied his mind. As Smith later recalled in his autobiography, “From a child I had always thought that I wanted to be free.”

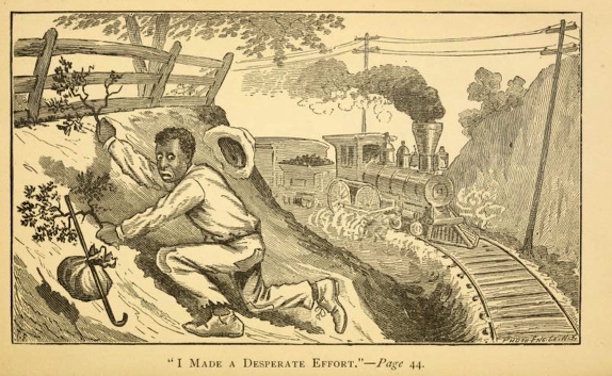

In the spring of 1838, Smith found a chance to escape in a canoe with two friends. After stealing a larger boat, they sailed up the Chesapeake Bay, landing in Maryland. From there, they proceeded on foot towards Delaware. Being lame, Smith soon fell behind, but continued doggedly onward and eventually rejoined his friends in New Castle.

After the three young men purchased passage on a ship bound for Philadelphia, Smith’s two friends signed on as sailors on an eastbound ship, once more leaving Smith on his own. Alone, conscious of his status as a fugitive, and uncertain what to do next, he met a Philadelphia abolitionist named Simpson, who took him home and gave him a good supper and a room for the night. Smith had reached the Underground Railroad.

How the Underground Railroad Operated

The Underground Railroad was a network of safe houses operated by anti-slavery activists to help fugitives from the South find their way north to freedom. Fugitives were called “passengers,” safe houses were “stations,” and the people who harbored the fugitives were “stationmasters.” “Conductors” were those who guided passengers from one station to the next.

Despite the relative novelty of the actual railway industry in the 1830s, the “Underground Railroad” was a well-established term by the time Smith made his escape—a term used both by proponents of the institution and those violently opposed to it. The term “railroad” suggested the speed and efficiency with which the system operated, and the adjective “underground” indicated the secrecy necessary to assure its success. During the decades before the Civil War, it helped thousands of former slaves escape to the northern states, Canada, or Europe.

The group of abolitionists that Smith encountered in Philadelphia included free black people and Quakers. They rejoiced over Smith’s escape and offered him a chance to go to England, but in the end decided to send him north to Springfield, Massachusetts. They put him on a steamboat to New York, giving him a letter addressed to David Ruggles, a native of Norwich, Connecticut, who served as a leader of the African American community in New York. Ruggles, in turn, gave Smith introductions to two men, in Hartford and Springfield, and sent him on his way on another steamboat, bound up the Connecticut River. In this way, passed from hand to hand, from one safe house to another, James Lindsey Smith reached safety in Springfield less than two weeks after escaping from slavery in Virginia.

Smith remained in Springfield for four years, pursuing his trade as a shoemaker and speaking out against the evils of slavery. Later, he traveled through western Massachusetts and Connecticut with an anti-slavery lecturer, encountering much prejudice and some violence. “Slavery at this time had a great many friends,” he wrote.

James Lindsey Smith Returns to Connecticut

In 1842, Smith married Emmeline Minerva Platt and moved to Norwich, Connecticut, where he established a successful business making and selling shoes. Within a few years he purchased half of a frame house on School Street, and later, a larger house on Oak Street. His daughters Louie and Emma attended Norwich Free Academy and became teachers. His son, James H. Smith, became a shoemaker, like his father.

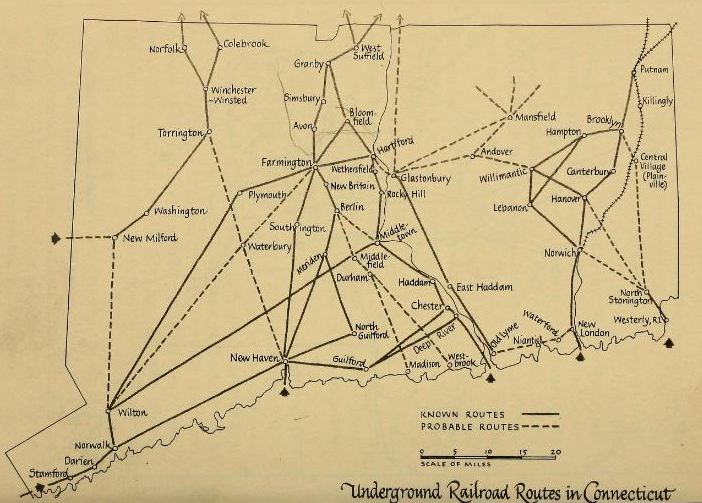

For Smith, as for many passengers on the Underground Railroad, Connecticut was both a way station and a terminus. Connecticut abolitionists helped Smith to make good his escape; Connecticut was his ultimate destination and became his home. During the 1830s, ’40s, and ’50s, many other fugitives arrived by ship as he did, landing in Hartford, New Haven, Norwich, and other towns along Long Island Sound and the Connecticut River. Some of them, like Smith, chose to make their homes in Connecticut. Others continued on to points farther north, traveling by well-established routes that often followed the river valleys. The reception they received depended upon the community in which they settled. Some found a sympathetic welcome while others found their opportunities limited because of their race. Many, like Smith, ultimately achieved success, despite rampant prejudice, and established free and fulfilling lives for themselves and their families.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.