By Steve Thornton

Free Speech in America? For working people in the early 1900s, this right was gravely restricted. Until workers and their unions fought for it—in the courts and in the streets—the First Amendment was an illusion for many Connecticut citizens.

In 1791, a sufficient number of states approved the Bill of Rights, which guaranteed that Congress could not infringe on the right of free speech or assembly (our state was not among those voting). But in practice, ordinary people could not speak on public property unless they won explicit permission from local authorities.

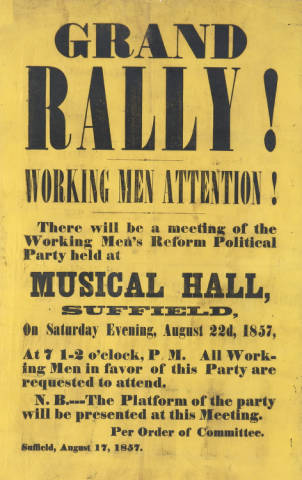

Grand rally! Working men attention! Working Men’s Reform Political Party, 1857. Broadsides M 1857w927g — Connecticut Historical Society

Laws Used to Suppress Union Movement

Hartford’s Amalgamated Trades Union wanted to use Bushnell Park for a mass meeting in 1884. The Board of Aldermen approved the rally. The Mayor vetoed the Board’s action. Special meetings were called to reject the veto and uphold the union’s request. “The general argument was that the park belonged to the people,” the Hartford Courant reported.

Despite that democratic sentiment, local authorities’ right to limit rallies or speeches on public property was affirmed by a US Supreme Court ruling (Davis v. Massachusetts) in 1897 when a reverend challenged a Boston law. The Court wrote that the Constitution “does not have the effect of creating a particular and personal right in the citizen to use public property in defiance of the Constitution and laws of the state.”

For the next four decades, local Connecticut activists suffered the consequences of that decision. Enforcers frequently targeted groups, including unions, suspected—rightly or wrongly—of being aligned with socialist or communist politics. In 1904, for example, union organizers were arrested for violating Torrington‘s “hand-bill law” when they distributed leaflets. In 1912, socialist Cornelius Foley tried to speak in downtown Hartford but was denied permission, forcing him to a corner where hustlers hawked medical cures and novelties. In 1914 another socialist began to talk in front of Parson’s Theater but was interrupted by a police officer. The soap-box orator was charged with breach of peace for speaking in public without a license.

Workers Use Civil Disobedience Tactics

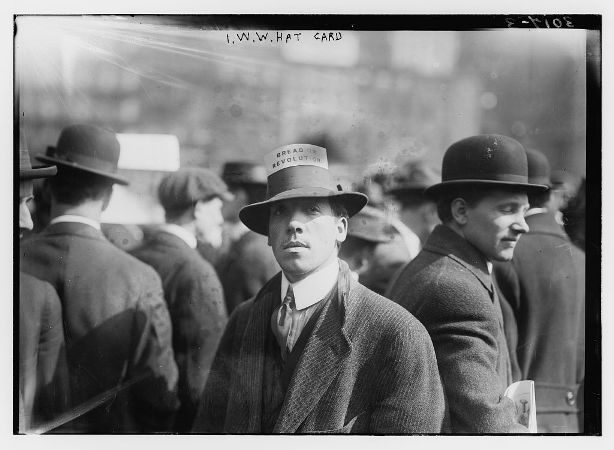

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), popularly known as the Wobblies, devised a strategy to win the freedoms that the law denied them. The radical union mounted “free speech fights” wherever authorities banned their organizing efforts. They defied local laws and filled the jails, forcing local governments to go broke or give in. Despite the terrible hardships they faced in jail, the Wobblies compelled cities from Spokane to San Diego to rescind legal prohibitions.

In Willimantic, IWW organizer J.T. Bienowski threatened to bring in dozens of other union activists to challenge a 1912 city ban on street speaking. He didn’t have to follow through on the threat: a month later 500 workers crowded Lincoln Square to hear Wobbly Ben Legere speak for over an hour with no police interference. In Bridgeport and Waterbury, however, IWW organizers defied similar city ordinances and paid the price.

In 1919 the Connecticut General Assembly enacted laws aimed at the IWW. Long jail sentences could be imposed for speaking in a “disloyal, scurrilous or abusive manner,” addressing 10 or more people in a way that could “injuriously affect” the state government, or carrying a red flag.

Not until 1939 did the US Supreme Court validate one of the basic concepts of free speech as we now know it. Again, a union championed the change. After the IWW was effectively disrupted by the government, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) took up the cause of America’s workers. In New Jersey, the CIO challenged political boss Frank Hague who, in 1937, had banned public union meetings by invoking a city ordinance that barred the assembly of persons seeking to obstruct government by unlawful means. The Court ruled that the use of public places was “a part of the privileges, immunities, rights and liberties of citizens.”

Although the ruling did not acknowledge past abuses of workers’ freedom of assembly, the First Amendment was finally becoming a reality for a greater number of citizens. And eventually, our state followed suit. In 1939, 150 years after its original passage, Connecticut finally ratified the Bill of Rights.

Steve Thornton has been a labor union organizer for 35 years and writes on the history of working people.

This article originally appeared on ShoeLeatherHistoryProject.com