By Nancy Finlay

The Cape Verde Islands—a group of volcanic islands in the Atlantic Ocean, 280 miles off the west coast of Africa—were uninhabited until the Portuguese discovered and colonized them in the mid-15th century. Beginning in the Age of Exploration, the islands served as a convenient stopover for vessels bound across the Atlantic and played a key role in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Many Portuguese settlers on the islands intermarried with Africans, resulting in a mixed-race population.

During the 19th century, the Cape Verde Islands remained a convenient source for fresh provisions and additional crew members for vessels setting out on lengthy voyages. These ships included whalers sailing out of New England ports. Young Cape Verdeans proved eager recruits, looking for adventure and seeking to escape poverty and the periodic famines that ravaged their islands. At the end of the voyage, the captain often discharged the entire crew at the vessel’s home port. Though some Cape Verdean sailors took their earnings and returned to their islands, others remained in the United States, signing on for additional voyages and making new homes in New England—including Connecticut.

Stories of Cape Verdean Sailors in Connecticut

Cape Verdean sailors began showing up in New London, Connecticut, at least as early as 1832. While most continued to follow maritime trades and appear in the census as seamen, sailors, mariners, or fishermen, a few found work in other professions. Among them was Antone De Sant who made his first whaling voyage out of New London. He made at least seven such voyages in all, rising in rank to become a ship’s officer. By 1840, he was the owner of two buildings on Bank Street, and he is listed in the 1850 census as a barber as well as a mariner. In 1842, he married a local woman, Diana Gager or Cager, but she died in 1856 and none of their four children survived to adulthood. His second wife was Susan Congdon, who was part African American, part Native American, and part white. By 1860, De Sant had left the sea and was running a grocery in one of his Bank Street buildings. He became a naturalized citizen in 1872 and died in 1886. He and Susan had several children, and some of their descendants still live in Connecticut today.

Trials at Sea

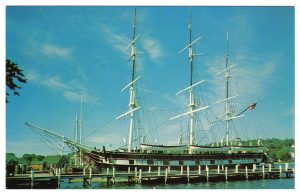

The Charles W. Morgan shown at her permanent berth at Mystic Seaport – Groton Public Library Collections

In addition to whales, Connecticut vessels hunted seals beginning in the early 19th century. Sealing became increasingly important as whaling declined towards the century’s end. The sealers’ chief prey was the elephant seal—a mammoth creature that could reach 20 feet in length and weigh up to three tons. Like whales, seals were hunted for their blubber, which was boiled down for oil. Unlike whalers, sealers shot or clubbed their prey to death on land when the seals came ashore to breed. Sealing was brutal and disturbing work, and as a result, it became increasingly hard to find men willing to participate in these voyages. Cape Verdeans, however, were often willing to sign on in the hope of finding a better life in the United States. Increasing numbers of Cape Verdeans took part in these expeditions as the century progressed.

Life at sea was always dangerous, and as whalers and sealers pursued their prey in remote corners of the world, they often encountered treacherous conditions. The schooner Pilot’s Bride left New London on a sealing voyage in 1880 with only eight men on board; she added 20 more on stops in the Azores and the Cape Verde Islands. The schooner was wrecked near Desolation Island in the South Indian Ocean, stranding the crew there until 1882, when they were rescued by another New London schooner, the Francis Allyn. Similarly, the bark Trinity—which also left New London in 1880 with a skeleton crew on board—stopped to pick up 19 “Portuguese negroes” in the Cape Verde Islands and proceeded to the South Indian Ocean in search of elephant seals. She ran aground on Heard Island, forcing her crew to overwinter before eventually being rescued by the Marion (a United States man-of-war). Although two of the other crewmembers froze to death, all the Cape Verdeans survived the ordeal.

Cape Verdeans Formed Integral Part of Crews

While Cape Verdeans formed parts of whaling and sealing crews since the early 19th century, they were initially a small minority. By the end of the century, however, it was not uncommon for most of the crewmembers on these Connecticut ships to be either Cape Verdean or Azorean. Cape Verdeans sometimes even rose to positions of authority on these vessels, serving as boatsteerers, harpooners, and ship’s officers. John T. Gonsalves, from the Cape Verdean island of Brava, joined a New London whaling crew as an 11-year-old cabin boy around 1869. He eventually became a whaling master and served as captain of the Charles W. Morgan (today berthed at Mystic Seaport) on her last whaling voyage in 1920-1921. With just two exceptions, all the other officers and crew on that voyage had Portuguese last names, and it is probable that, like their captain, many of them originally came from the Cape Verde Islands.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.