Last Updated: June 24, 2025

By Kate Steinway

Americans of the late 1800s took pride in the burgeoning cities that had sprung up across the nation as a result of innovations in transportation, wide-spread industrialization, and massive population growth fueled by immigration. Even small communities that retained much of their village character boasted of their few factories and commercial enterprises.

This civic pride found its ideal—and idealized— expression as a lithographed panoramic vista of the city or town rendered as seen from a high vantage point, or “bird’s eye” view. From the 1850s to early 1900s, thousands of American communities, including 77 in Connecticut, posed for this new kind of urban/town portrait. The O.H. Bailey & Co., a prolific Boston-based publisher of bird’s-eye views from the late 1870s to the early 1900s, produced many of these.

Capturing the Changing Face of Connecticut

As with any formal portrait, bird’s-eye views presented the city or town in its best possible light. Every detail became an optimistic advertisement for progress. Artists took care to include new structures (factories, bridges, railroad tracks and stations, gas works, and reservoirs, some not yet completed), new concepts (business districts, public parks, and suburbs), and civic institutions (jails, almshouses, public schools, and hospitals). These physical markers of a community’s achievements often appeared greatly exaggerated in size.

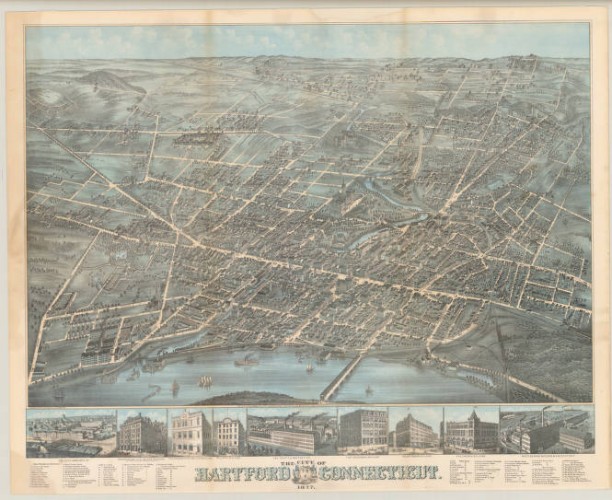

In contrast, undesirable aspects of urban expansion, such as slums, crowds, sewage, or muddy streets, were masked or minimized. Much can be learned about Victorian Connecticut’s attitudes toward the transformation of their communities by considering what artists included, what they left out, and how they composed a bird’s-eyes scene. A case in point is Hartford’s Park River, depicted in an 1877 view of the city as a pleasant stream when, in fact, documents of the time indicate that it was little better than an open sewer.

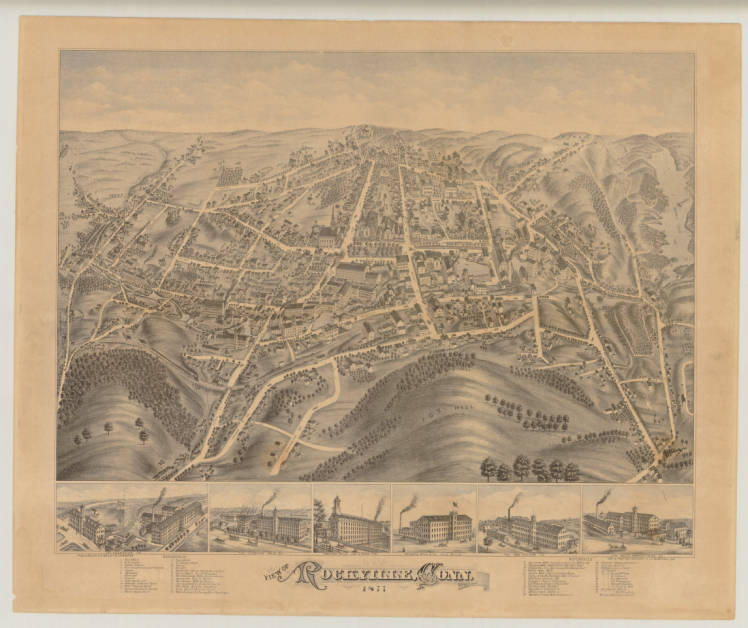

View of Rockville, Conn., Boston: O.H. Bailey & Co., 1877 – Connecticut Historical Society

Studying bird’s-eye view lithographs can also reveal the ways in which industrialization changed Connecticut’s towns and cities. Two views of Rockville, one from 1877 and the other done in 1895, provide an informative comparison. The artist of the earlier view appealed to citizens’ civic pride by exaggerating signs of the textile mill town’s prosperity. For example, the mills along the Hockanum River (seen in the center of the print) as well as the churches, opera house, and two public schools (all at upper center and right) are much larger in scale than the homes surrounding them.

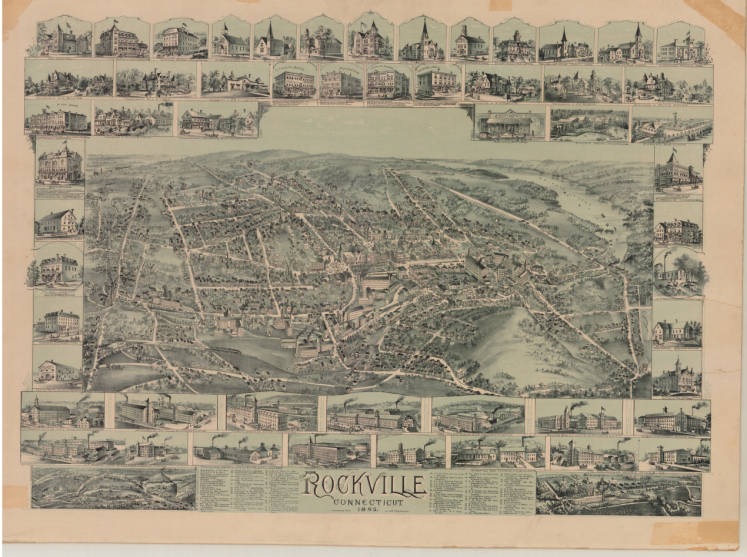

Comparing this view to the one produced 18 years later provides evidence of the textile industry’s growth. The most obvious change is the greater density of development within town limits. Also, the single mill buildings seen in the 1877 view have, by the time of the 1895 rendering, become large complexes. For example, the New England Company grows from one large building with a few smaller ones clustered about it (#23 in the lower left of the 1877 print) to three large multistory buildings.

Rockville, Connecticut, Boston: O.H. Bailey & Co., 1895 – Connecticut Historical Society

An Enterprising Art

Town views were commercial enterprises orchestrated by lithograph publishers. (Lithography, a chemical printing process, became popular in the 19th century because it allowed images to be reproduced more quickly and at a lower cost than other methods such as engraving.) Typically, a publisher employed an itinerant artist to draw a town. The artist spent several weeks in a community consulting atlases, maps, and land records in addition to walking along the streets sketching specific buildings.

To stir up attention, a notice of the artist’s arrival was usually placed in the local newspaper. When finished, the artist’s drawing was displayed for several days in the window of a local bookstore, newspaper office, or community building to give residents an opportunity to point out any errors and to whet their appetites for the lithograph to follow. During these weeks, an agent of the publisher visited the town placing newspaper notices and going door-to-door to solicit advance subscriptions from local residents and businessmen. Individuals, businesses, and municipal officials, all eager to promote the virtues of their communities, bought the prints as decorations for homes and offices.

Several months later, the agent came back with the lithographed views. Admiring notices appeared once again in newspapers, subscriptions were delivered, and those who did not order a copy of the view were given a second chance to do so. A typical print run for a Connecticut bird’s-eye view numbered between 100 and 300 copies. They sold for $1.50 to $3.00 each, depending on coloring and size.

Selling the Virtues of Industrialization

Once lithograph publishers figured out the process for drawing, producing, and marketing the place-specific prints, it became a routine process to turn out bird’s-eye views of any and every city and town in the United States. The similarity of the views carried with it an inherently soothing message, one which must have helped Americans across the nation adjust to the many changes in their environment. At the same time, these prints, like the good advertisements that they are, indoctrinated the public with the idea that urbanization and industrialization were positively transforming America’s landscape. It is no accident that the growing trend toward national marketing and the increasing prominence of American industry (for both good and ill) at home and abroad coincided with the boom in bird’s-eye view prints.

For the maker of bird’s-eye views, the challenges inherent in depicting a community included representing its diversity on a manageable scale and depicting the multiplicity of its parts in a coherent whole. Equally demanding were the tasks of composing an accurate yet optimistic representation and conveying a three-dimensional sense of space in a two-dimensional print. For the 19th-century viewer, the maker’s mastery of these challenges through a skillfully composed bird’s-eye view rendered the new, multifaceted, and increasingly overwhelming urban spaces comprehensible and concrete.

The Popularity of Bird’s-Eye Views Wanes

By the turn of the 20th century, bird’s-eye views began to diminish in popularity. Tastes in interior decorating changed, and rapid growth in cities rendered many views out-of-date almost as soon as they were printed, which made them less appealing. Hand-drawn bird’s-eye views were finally made obsolete by the real thing: aerial photographs taken from newly invented airplanes.

Today, bird’s-eye views are recognized as valuable documents of the industrialization and urbanization of the US. Studying the changes in Connecticut town views from the 1840s through the early 1900s is an opportunity to examine how artists, publishers, and marketers made the state’s emerging urban spaces palpable—and palatable—to the people who lived in them.

Kate Steinway, formerly Executive Director of the Connecticut Historical Society (now the Connecticut Museum of Culture and History) in Hartford, curated the traveling exhibition, Hamlets & Hubs; Bird’s-Eye Views of Connecticut Towns, 1849-1908 (1987-88), from which this article is derived, while Curator of Prints and Photographs at CHS.

This article has been updated, learn more about content updating on ConnecticutHistory.org here.