By Nancy Finlay

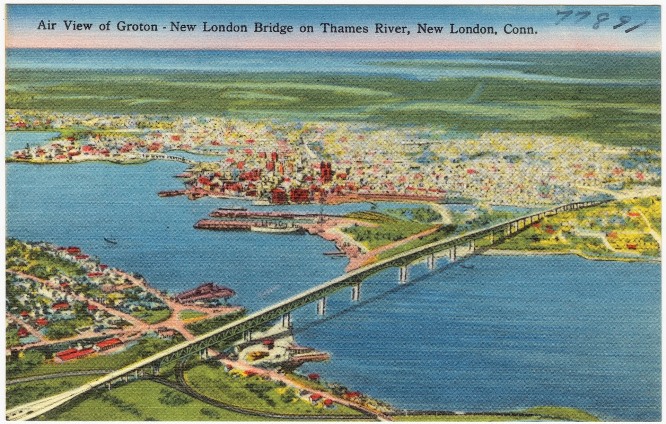

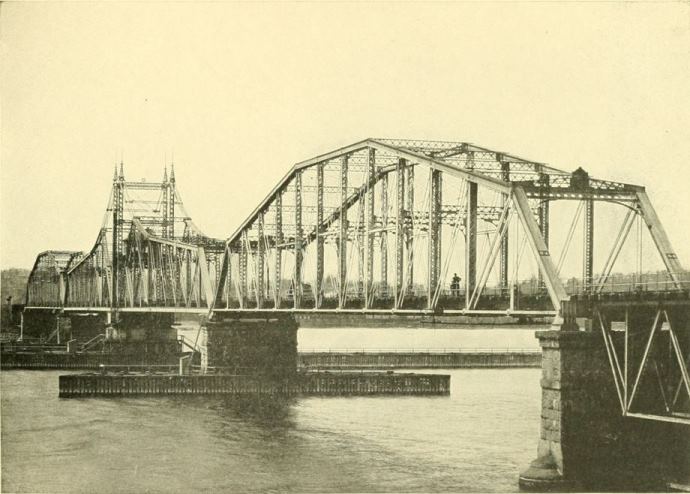

The Thames River crossing at New London has always been a critical point on the overland route from New York to Providence, Rhode Island. Initially, travelers relied on a ferry to help them complete their journey through southeastern Connecticut. Additional help came in the late 19th century in the form of a railroad bridge that carried people and freight across the river. Later, upon the arrival of the automobile, authorities built a new railroad bridge and converted the old bridge for use by cars and trucks, but even this soon proved inadequate.

Photograph of the “Railroad Bridge over the Thames” from Views of New London, 1908

The Gold Star Memorial Bridge

Construction of a new highway bridge across the Thames River between New London and Groton began in 1941. Despite delays caused by the United States’ entry into World War II, workers completed the bridge for its opening to the public on February 27, 1943. In 1951, officials renamed it the Gold Star Memorial Bridge in honor of servicemen who gave their lives in World War I and World War II.

With the postwar development of the Interstate Highway System, the single-span bridge soon proved unable to handle the ever-increasing flow of traffic. In 1963, planning began for a second span to carry additional lanes of traffic and for an elaborate interchange connecting the highway with local roads, and a year later, the bridge officially became part of Interstate 95.

Local businessmen opposed the original plan for the new bridge, which called for the elimination of Hodges Square, a flourishing business district with appliance stores, bakeries, food markets, and plenty of parking. The Hodges Square Businessmen’s Association protested the destruction of the area. Eventually officials approved an alternate plan that “saved” Hodges Square, though cynical city officials predicted that the businesses would “wither away” once the highway entered service and the area found itself cut-off from the rest of the city.

I-95 Construction Carves Up New London

The new highway ramps cut through densely built-up areas occupied by houses, businesses, and historic sites in New London. One ramp looped around the Old Town Mill, a structure originally constructed in the 17th century and rebuilt following the burning of New London by Benedict Arnold during the Revolutionary War.

Photograph of the “Old Town Mill, Built 1650” from Views of New London, 1908

Officials seized entire blocks by right of eminent domain and tore them down to make way for the highway. The 1773 Nathan Hale School House, where the patriot spy taught from 1774 to 1775, had to be moved from a site on Crystal Avenue (not its original location) to a more accessible site downtown. The rectory of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, a Roman Catholic church built to serve Polish immigrants to New London, had been torn down when the first span of the bridge was built. When the second span began to emerge, the church itself was in the way and had to be moved to Watertown, leaving its parishioners behind in an area that was becoming increasingly marginalized. A firehouse, a school, and numerous other structures were also in the way of construction and had to be relocated.

Traffic patterns changed as construction proceeded and the district slid into what appeared to be an irreversible decline. Riverside Park, a popular destination in the early 20th century, also wound up on the “wrong side” of the highway. Early postcards show winding drives, grassy lawns, and spectacular views of the Thames River, but by the 1970s, the park became much reduced in size and few amenities remained.

Historic Preservation Efforts

In the 1960s and 1970s, many simply viewed these changes as the price of progress. The same thing was happening in other cities in Connecticut, and all across America. To combat the loss of important sites, historic preservation efforts focused on significant architectural monuments. In New London, for example, successful efforts managed to save such buildings as the H. H. Richardson train station and a series of Greek revival houses known as Whale Oil Row.

It was not until the 21st century that preservationists began to take a broader approach, however, preserving or restoring whole neighborhoods. Efforts to revitalize Hodges Square began in 2012 with the creation of a master plan to reconnect the area with downtown New London. The location, sandwiched between Connecticut College and the United States Coast Guard Academy and in close proximity to the river, has become a symbol of New London’s efforts to revitalize a once-thriving commercial district.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.

Photograph “A View of Riverside Park,” New London from Views of New London, 1908