By Edward Baker for Connecticut Explored

September 6, 1781 was a brutal and terrifying day for Connecticut citizens living on both sides of New London harbor, along the Thames River. On that day 1,700 British, Hessian, and Loyalist troops, under the command of General Benedict Arnold, achieved the last British victory of the Revolutionary War, committing acts of urban terrorism and slaughter that would define those communities for years to come. “Arnold’s Raid on New London,” as it was later called, had more to do with spite than strategy. But the raid, occurring almost exactly one year after the discovery of Arnold’s plot to turn George Washington’s army and headquarters over to the British and Arnold’s subsequent escape to the British, cemented Arnold’s reputation as America’s most notorious traitor.

But the events leading to the burning of New London were rooted in circumstances far deeper than simple spite. A confluence of geography, world trade, and wartime economics turned New London (and neighboring Groton) into hotspots of historic import.

A Bustling Port Turns to Privateering

The Thames River provides New London with an excellent harbor. It is wide and deep, the bottom has excellent mud for anchoring, it hardly ever freezes over, and its location at the eastern end of Long Island Sound allows ships easy access to the Atlantic Ocean. During the colonial period, New London’s wharfs bustled with activity stemming from the active “West Indies trade,” whereby the farm products of New England were exchanged for sugar, rum and molasses. Sugar cane was about the only crop grown on the islands of the Caribbean, so plantation owners were completely dependent on imports of livestock, food, and supplies from the English colonies to the north to feed themselves and their slave labor. Sugar, molasses, and rum happened to be the primary commodities that could be used in trade with England. Merchants in New England, in particular, profited by shipping supplies from the northern colonies to the Caribbean, sugar, molasses and rum to England, and English goods back to the colonies.

The Birthplace of Benedict Arnold, Norwich – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Goods coming into the colonies from foreign ports (such as rum, sugar, wine, and tea) were subject to duties–import taxes–to be paid to the British government. But it was difficult to enforce such regulations along New England’s long coastline. As these duties increased in the 1760s to pay for England’s wars with France, smuggling became big business. Bringing those commodities into port without paying duties to the King was so common as to be called part of the “constitution” of the Connecticut citizen. Many of these New England captains and merchants also fervently opposed further British taxation.

New London’s anti-tax and, by extension, anti-British sentiment made it a natural harbor for the Continental Congress’s first forays into naval resistance. As the only deep-water port between British-held Newport, Rhode Island, and British headquarters in New York, it was the perfect location from which to launch attacks on British shipping.

The Continental Congress established a navy early in the war. But limited funds required reliance on the states to supply ships, which were slow to materialize. Just as the Continental Congress looked to its citizen soldiers for its army, this revolutionary government also licensed privately owned armed vessels to serve as part of its navy. Commanders of such ships were known as privateers; their motivation was to support the cause of liberty while also supporting themselves.

Attacking the mighty British navy head on with such a small navy would have been foolhardy. Instead, the Americans adopted the age-old strategy of commerce raiding, plundering enemy merchant ships for military supplies and other goods. The first naval force of the Continental Congress was fitted out in New London and returned there after a raid on Nassau to acquire military supplies. The warehouses of New London became storehouses for the revolutionary cause.

The difference between piracy and privateering, in essence, is one piece of paper, a commission, sometimes referred to as a letter of marque. These documents were printed forms with blanks to fill in the name and size of vessel to be registered as a privateer, the name of captain and owner, the number of guns, and the size of the crew. The owner was required to provide bonding: should his crew seize a vessel that was not an enemy ship, he would be liable for expenses. Privateers were also required to follow a series of published regulations or rules of engagement.

The number of guns and size of crew was important, as the usual practice was to sail upon a merchant vessel that was believed to be not well armed, determine that it was a British ship, threaten to blow the ship out of the water should its captain not surrender, assign a crew of one’s own men to take over the sailing of the enemy ship, and sail it into New London. There the ship and cargo would be sold at auction and the spoils distributed to the owners, captain, and crew. So it should be no surprise that privateers could get all the crew that they wanted, while commanders of militia units near ports found it hard to compete with the privateers to get the quota of soldiers they needed. Indeed, Colonial William Ledyard, commander of the forts protecting New London harbor, complained frequently that he had not enough cannon, not enough powder, and not enough men.

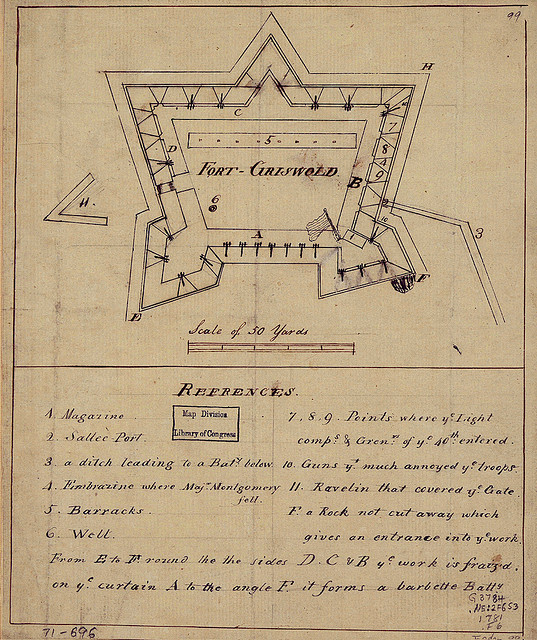

Fort Griswold, 1781- University of Connecticut Libraries’ Map and Geographic Information Center (MAGIC)

New London’s Strategic Role

Before the war, New London had a few cannon in the center of town overlooking the river at the end of “the parade,” the main market square. In 1778 a fort was erected on the New London side on a rocky outcropping south of the main part of the city and named Fort Trumbull, after Governor Jonathan Trumbull. On the Groton side, on a prominent hill very close to the river, another fort was erected and named Fort Griswold, after Deputy Governor Matthew Griswold.

Privateering generates a considerable amount of activity, including the adjudication of prize ships, exchange of prisoners, and acquisition of cannons and powder for the government. All this activity required supervision, so the Continental Congress appointed a naval agent for each state. Wealthy New London merchant, ship owner, and patriot Nathaniel Shaw, Jr. received the commission as naval agent for Connecticut in April 1776. When Washington came through New London after forcing the British evacuation of Boston in spring of 1776, there was a grand assemblage of army and navy. Ezek Hopkins, commander of the navy, had just returned to New London from Nassau. Washington, Hopkins, General Nathanael Greene, and other officers shared dinner at Nathaniel Shaw’s house, where Washington was given the master bedroom for the night. Shaw’s commission as naval agent was signed by John Hancock two weeks later.

Shaw profited from the war as owner of 10 privateers and part owner of 2 more. During the war, at least 4 of these privateers were captured. Another ran aground, and yet another was burned to prevent its falling into British hands. But his 12 ships captured 57 prizes. A schooner, the General Putnam, was the one burned in 1779, but it captured 14 prizes before it was lost. The American Revenue, a sloop, took 15 prizes; and the Revenge, also a sloop, 19.

Shaw’s success attracted partners. Benedict Arnold, in fact, wrote to Shaw asking to be included as an eighth- or sixteenth- part owner of a Shaw privateer; a later letter from Arnold asked to be released from the arrangement once he found that he could not afford the cost.

Benedict Arnold’s Long Journey Back to New London

In late July of 1781, the British merchant ship Hannah was seized and brought into New London by the Minerva, captained by Dudley Saltonstall. She was the largest prize taken during the entire war, with a cargo of West India goods and gunpowder whose value was estimated at 80,000 pounds sterling. The loss spurred the British to retaliate, to punish New London for its success at privateering. Who better to command this attack than Benedict Arnold, born and raised only 10 miles away, in Norwich, and anxious for a command and to demonstrate his newfound loyalty to King George III?

Benedict Arnold house, New Haven – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Illustrated

Arnold was 34, living in New Haven, and serving as captain of a militia company when the British attacked Lexington and Concord in 1775. He had served an apprenticeship to apothecary cousins in Norwich but ran off in 1758 to serve in the army in New York in the French and Indian War. He later traveled to the West Indies and to England, where he purchased supplies and made contacts to open his own apothecary shop in New Haven. He acquired some wealth, married, and began a family. When he heard of the British attacks in Massachusetts, he rushed off to assist in ridding Boston of the British.

It was Arnold who devised the idea of capturing Fort Ticonderoga to acquire its cannon, which were needed to force the British out of the city. Arnold was given a command and charged with taking Ticonderoga when he met up with Ethan Allen, another Connecticut-born revolutionary, who was commissioned by Connecticut to do the same thing. Neither one willing to serve under the other, they stood side by side as the Fort was taken. Arnold may have had the more legitimate right to be in charge, but Allen, who had the manpower to take the fort, ultimately got the credit for this first American victory.

Thus began a pattern that was repeated throughout the war: Arnold performing bold, even heroic deeds-at Quebec, on Lake Champlain, at Saratoga-but not being afforded the honor, the recognition, or the rank he thought he deserved. At Saratoga he led two charges of other officers’ companies, despite having been relieved of command by General Gates. While these attacks ensured the American victory, Arnold’s leg suffered a grievous wound. Again a hero without official recognition, Arnold went to Valley Forge to recover. George Washington later placed him in command of the city of Philadelphia in July 1778 after the British evacuated that city.

Serving as military commander for the political center of the Revolution was undoubtedly not the best role for the impetuous and risk-taking Arnold. Hobbled by a leg that he refused to have amputated, possessing a strong sense of his own importance, and determined to receive full measure of consideration from others, he bristled under the watch of Congress. Likewise determined to enjoy his status, he dove into the Philadelphia social scene, which only the previous winter had revolved around the British officer corps. Arnold, 38 at the time and recently widowed, pursued and won the affection of one of the premier young ladies of the city, 18-year-old Peggy Shippen, daughter of a judge, Edward Shippen.

Once married, the Arnolds maintained an extravagant household that was beyond the general’s means. Congress itself was almost bankrupt and parsimoniously refused to honor many of Arnold’s vouchers and accounts for his military campaigns; Arnold was eventually court-martialed for taking advantage of his position for financial gain. Driven by lack of recognition, the accusations of wrong-doing, the want of money, and his wife’s loyalist stance, Arnold came to the conclusion that the Revolutionary cause was doomed. Using friends of his wife as intermediaries, Arnold began secret negotiations with British commander General Henry Clinton.

Those talks began in May 1779 and continued to August 1780. In the meantime, Arnold requested and was given command of West Point-Washington’s headquarters. Finally, the British proposed their deal: If Arnold delivered West Point, its artillery, stores, and 3,000 men, he would receive 20,000 pounds.

But Arnold’s plot was discovered. In September 1780, Major Andre, the courier between Arnold and Clinton, was captured near Tarrytown, New York, with maps and a pass through the lines from Arnold. Arnold escaped to the British ship Vulture, and Andre was hanged. Though he had not delivered West Point to the British, Arnold was given 6,000 pounds and the rank of provincial brigadier general. That winter he was sent to Virginia, where he sailed up the James River with a force of 800 men, set fire to the warehouses of Richmond, and then was placed briefly in command at Hampton Roads. By June 1781 he was back in New York.

Arnold Delivers a Devastating Blow to New London

Through the spring and early summer of 1781, three thousand French troops under Rochambeau marched from Newport, Rhode Island, across Connecticut to join with Washington’s forces on the Hudson River. Although it was Washington’s plan to attack New York with the joint force, by late August the leaders had agreed to shift their plan and instead attack General Cornwallis in Virginia, where the French navy had succeeded in cutting off British support by way of the sea. Through late August the French and American forces marched south through New Jersey, maintaining the illusion as long as possible that they were about to attack New York.

By September 2 it was clear, though, that Virginia was the target. At precisely this time, General Clinton agreed to a small diversionary tactic: a punitive raid on New London. On September 5, as French troops marched through Philadelphia on their way to the Chesapeake River to be transported south, British troops were on their way east on Long Island Sound.

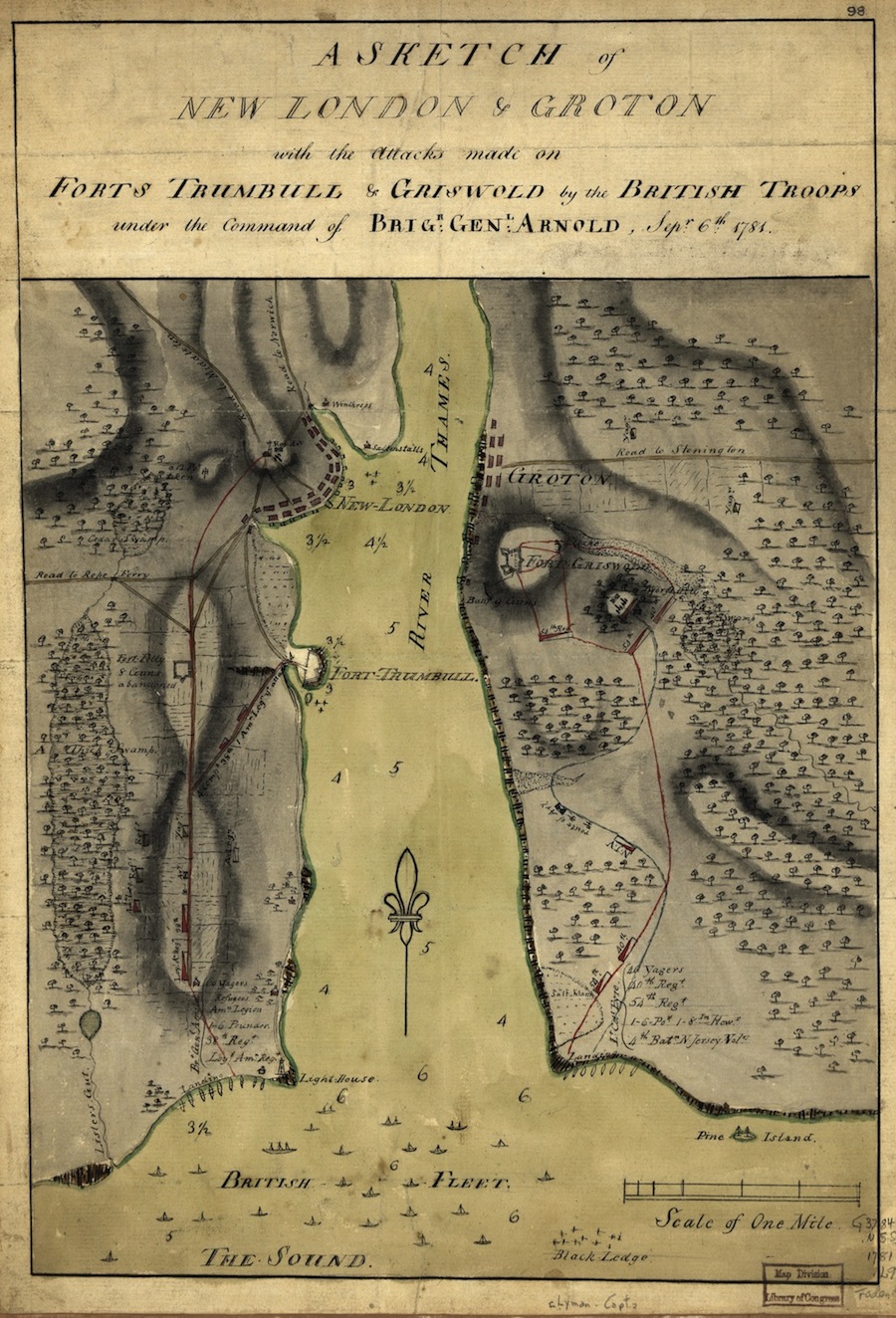

A sketch of New London & Groton with the attacks made on Forts Trumbull & Griswold by the British troops under the command of Brigr. Genl. Arnold, Sept. 6th, 1781 – Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

Arnold landed half his force on the New London side of the Thames River under his own command, sending the other half, under the command of Colonel Edmund Eyre, to take Fort Griswold on the Groton side. Colonel William Ledyard, in charge of the forts, had about seven hours’ warning between the sighting of the ships and the landing of the troops. He decided to concentrate on a defense of Fort Griswold and did all in his power to gather recruits. Several of the privateers in town attempted to get underway to sail up river toward Norwich to avoid attack.

Arnold’s force met some musket fire as they landed but found little resistance as they marched from the landing to town. There they split into two groups, planning to burn the city from both ends and meet in the center. Nathaniel Shaw’s house was one of the first set ablaze, but, as it was built of stone, neighbors were able to extinguish the flames before they consumed the structure. “Through the whole of Bank Street, where were some of the best mercantile stands and the most valuable dwelling houses in the town, the torch of vengeance made a clean sweep,” the Connecticut Gazette reported a month later. More than 140 buildings-homes, shops, warehouses-were destroyed, as were ships at the wharves. The Hannah was set on fire; when the gunpowder in her hold exploded, it helped to spread the flames.

At Fort Griswold on the Groton heights, approximately 160 militiamen and civilians gathered to fight the 800 British and Hessian soldiers. Refusing to surrender when that option was offered, they fought furiously, killing 2 English officers and 43 others and wounding 193 more. After about 40 minutes, the British made it into the fort. Colonel Ledyard, realizing all was lost, commanded his men to put down their arms. At that point there were an estimated 6 American dead and 20 wounded. But after giving up his sword, Ledyard was immediately run through, and the British troops, after losing officers and so many of their comrades, refused to be held back. When the slaughter ended, 83 Americans were dead and 36 wounded. Several of the wounded died within a few days. Those who could walk were taken as prisoners back to New York.

One month later, as Lafayette led his troops at Yorktown, he challenged his men to “Remember New London.” Cornwallis surrendered in October, and by January many British officers were being sent back to England. Cornwallis and Arnold crossed on the same ship.

New London and Groton were almost entirely leveled. Shaw was able to exchange prisoners after the Yorktown surrender. In December 1781 he brought some to his own home, one of the few structures still standing. Caring for these sick men, his wife Lucretia became ill and died of fever.

Due to the death of so many of Groton’s citizens, the Fort Griswold site almost immediately took on shrine-like status. A monument was erected there in 1830 and enlarged in 1881. The site was turned over by the federal government to the state in 1931, at the 150th anniversary commemoration of the battle.

Arnold and his wife, Peggy, lived out their lives in England trying, with limited success, to keep up appearances. Arnold was frequently the butt of jokes and deprecating remarks; once he felt he had to defend his honor in a duel (his shot misfired; his opponent, Lord Lauderdale, refused to shoot). He attempted to get rich in the West Indies and Canada, but he died in 1801 in relative obscurity. Peggy died only a couple of years later, having received her own annual pension from the King for her service.

In New London, Arnold’s name is still invoked whenever the city is under siege. After the Hurricane of 1938, newspaper headlines read “Worst Destruction Since Arnold’s Raid.” When urban renewal in the 1960s and 1970s leveled block after block, Arnold was jokingly called “the godfather of New London urban planning.” Even now, as New London struggles with issues of redevelopment and eminent domain, a local columnist recently linked the efforts of the redevelopment authority to those of Benedict Arnold.

Edward Baker is the Executive Director of the New London County Historical Society.

©Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 4/ No.4, Fall 2006.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.