By Steve Thornton

Eager newspaper reporters dubbed the gathering a “bombology class.” Federal agents targeted a nest of suspected radicals in South Manchester, Connecticut. The site was a small automotive garage where Russian immigrants met on a regular basis, and authorities figured they must be up to no good, learning how to construct “infernal machines,” as homemade bombs became known.

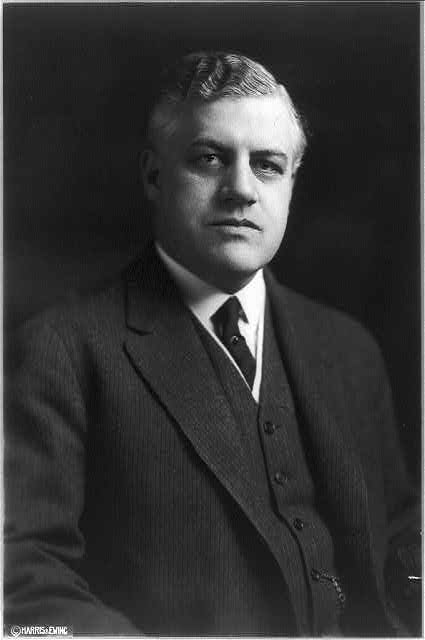

It was November 7, 1919, the first day of the notorious Palmer Raids, named after the US attorney general who led them. A. Mitchell Palmer’s Connecticut campaign began a nationwide sweep of thousands of workers, many of them immigrants, designed to rid the country of all dangerous “Reds.”

Attacks launched simultaneously in Bridgeport, Waterbury, Hartford, New Britain, and New Haven. The goal was to dismantle a “nationwide plot” for a “revolution planned by a reign of terror,” according to one Connecticut newspaper. Concern about the recent revolution in Russia and fear of growing labor unrest helped fuel this massive crackdown.

Backdrop to the Red Scare

The new Espionage Act and strict immigration laws gave the government power to criminalize free speech. Demands for wage increases and workplace safety became labeled un-American. Criticism of capitalism’s excesses was evidence of “Bolshevik” tendencies. Hundreds faced jail time for simply expressing their opposition to the First World War (ironically, some of those arrested were war veterans themselves). Postmaster General Albert Burleson attempted to clarify the laws’ purpose: “For instance, papers may not say that the Government is controlled by Wall Street or the munitions manufacturers or any other special interests,” he explained. Similar city and state laws against “disloyal” speech and publishing soon passed in Connecticut. Individuals became outlaws, not for what they did, but for what they thought.

Authorities secretly planned the Palmer Raids months in advance. Palmer’s assistant, the young J. Edgar Hoover, ran the operation. In a number of cases, Hoover planted spies within political and labor organizations; these agent provocateurs established trust within a group, enabling them to call membership meetings, thus allowing police to coordinate their raids.

A Bomb-Making “Ringleader”

Authorities arrested Mark Kulesch on the night of November 7 at his home. They considered Kulesch Manchester’s bomb-making ringleader since he was secretary of the local Union of Russian Workers. According to some news reports, he was in possession of a “full set of drawings” for machine gun designs from the Colt Firearms Factory, as well as “two small machine guns.”

Classified by federal authorities as an “enemy alien,” Mark Kulesch had no right to a trial. It did not matter that the mechanic was a volunteer in the “Americanization” effort to teach English and trade skills to fellow immigrants. Florence Hillsburgh, who led the education program, reacted angrily to his arrest. “This is getting to be a hysteria,” Hillsburgh told a reporter, “It seems that all a man has to be to get arrested by federal authorities is a Russian.”

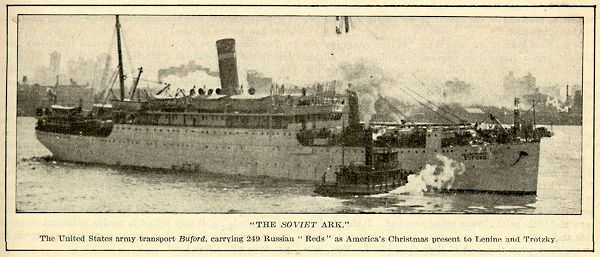

After six weeks in the Hartford Seyms Street jail, Kulesch joined 248 other prisoners from across the country placed aboard the USS Buford (nicknamed “the Soviet Ark”) and deported to Russia on December 21.

“The Soviet Ark”: The United States Army transport Buford, carrying 249 Russian “Reds.” Literary Digest, January 3, 1920 – Red Scare image database

The growing “red scare” atmosphere affected many others in the state, both immigrant and citizen. Politics forced Edward P. Clarke to resign his position as head of the Employment Bureau, a government job he held for more than four years. His association with the Socialist Party and as a leader of a peace group somehow proved evidence of disloyalty.

High school student David Sohn faced the threat of expulsion after a report that he made un-American remarks at the school’s debating club. When Sohn finally got to speak for himself, he explained what he said: if authorities rounded up radicals, they should arrest industrial war profiteers too.

At the Seyms Street jail, police arrested visitors when they came to see the prisoners. Palmer explained that the visits were the same as attending a revolutionary meeting and proof enough of guilt.

“Lenin’s Dream” a political cartoon by Clifford Berryman, 1920, Washington Evening Star – National Archives

Between November of 1919 and February 1920, authorities arrested and imprisoned 235 Connecticut men and one woman. Nationwide raids on January 2, 1920, led to the jailing of as many as six thousand alleged radicals. Many spent weeks or months behind bars, held incommunicado. Prisoners did not know the charges against them. Authorities denied some prisoners timely legal counsel or the use of interpreters. Bail costs proved astronomical for these working men.

Support for the Palmer Raids

The Palmer Raids had many boosters among business leaders, politicians, and the press. One Waterbury newspaper editorial applauded the effort to “put a leash on violent aliens.” Industrialist Clarence Whitney donated $50,000 to stop radical labor influence in Connecticut factories. The American Legion pledged its 12,000 state members to root out non-citizens for trial by a military court and death by firing squad. Retired bicycle maker George Pope called union activists “a new species of plague” to be treated like “brazen traitors.” They were “criminals by profession and by heredity,” he charged.

Reverend Howard Moss of Hartford’s First Methodist Church expressed the underlying cultural and class prejudice that stirred public support for the Palmer Raids. He told his Sunday flock that immigrants were “a sodden, bitter mass of humanity…low living in filth and poverty.” If you look a radical in the face, Moss warned, “behold it is the face of a foreigner.”

The Palmer Raids were just the beginning of the larger “Red Scare” that continued through much of the 20th century—a broad sweep that disrupted families, meant the loss of employment, caused paranoia in communities, and became a weapon against effective union organizing and government reforms. Some alarmists even decried Social Security as a socialist plot.

Exposing Law Enforcement Abuses

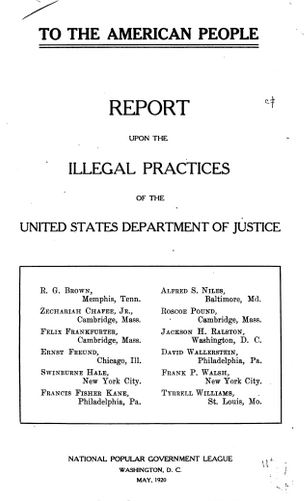

To the American People; Report Upon the Illegal Practices of the United States Department of Justice, National Popular Government League, 1920

The Nation magazine helped lead the fight against the 1919–1920 nationwide jailings. The magazine reported on the findings by a committee of well-known, highly respected legal scholars who investigated Palmer’s actions. One of those jurists was Felix Frankfurter of Massachusetts (later appointed to the Supreme Court in 1939 by Franklin Roosevelt). Their May 1920 report exposed significant civil and human rights violations. Prominently featured was the Seyms Street lockup. The committee criticized the use of four particular cells—called punishment rooms—that held the political prisoners. The cells, located directly over the jail’s boiler room, often had floors so hot they burned an inmate’s hands or feet. There were no windows and no light bulbs. Prisoners held in these rooms received one glass of water and a slice of bread every twelve hours.

Palmer’s methods and intent did not receive universal approval. “The very agencies which should be foremost in preventing (radicalism) have been, and are now, very busy creating it,” wrote one Connecticut editorial. The raids used “brutality, torture, forgery, theft—provoking crime in order to detect it,” charged the Nation.

In retrospect, even the FBI proved unable to defend Hoover’s 1919 “Red Scare” activity. “The Palmer Raids were certainly not a bright spot for the young Bureau,” the FBI recently admitted. “Palmer and Hoover were roundly criticized for the plan and for their overzealous domestic security efforts.”

Steve Thornton is a retired union organizer who writes for the Shoeleather History Project